Executive summary

- At first glance, the U.S. retail industry is the typical case of what the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter called “creative destruction”, in which new entrants capture growth or create new markets altogether at the expense of established companies. In the long run, creative destruction is supposed to have a net positive impact on the economy; however, judging from figures pointing to shrinking company count, employment and profitability, e-commerce isn’t compensating for the destruction of physical retail.

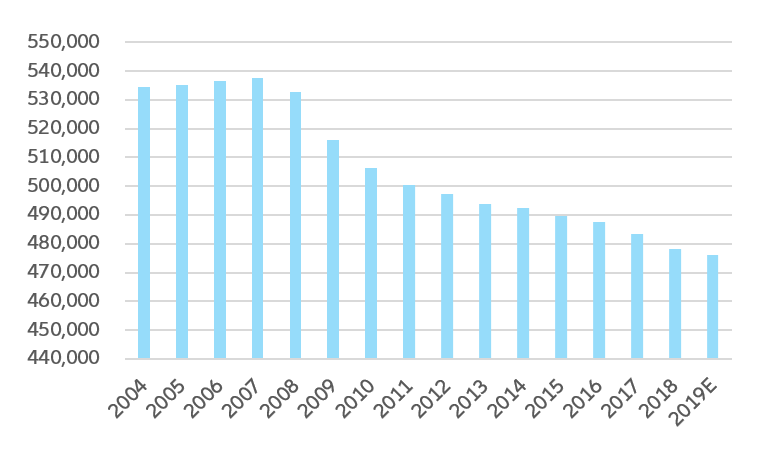

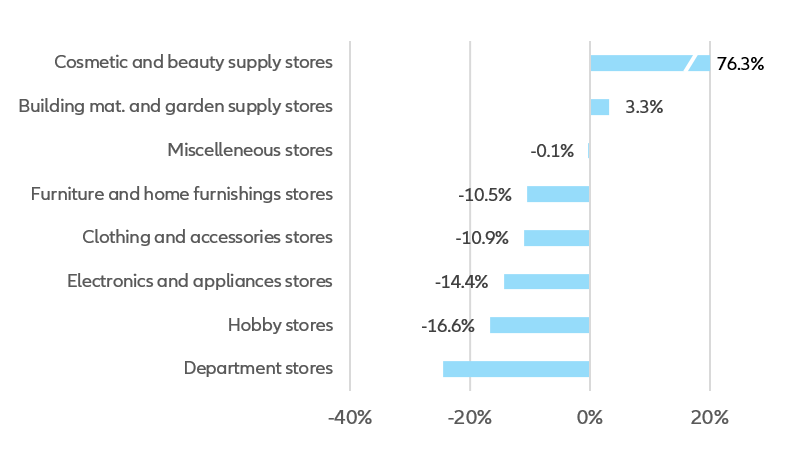

- The U.S. has lost more than 56,000 stores, or 10.7%, of its discretionary retail footprint since 2008, despite healthy spending on discretionary consumer goods. Employment data depict a similarly gloomy picture, with 670,000 net job destructions since 2008 (-9.6%). For one job created in e-commerce, four and half jobs are lost in traditional discretionary retail. The segment breakdown shows a broad-based decline largely consistent with e-commerce penetration, which is the highest for hobby goods (toys, books, music and video content, etc.). Shoppers’ growing taste for online orders has also hurt shopping mall footfall and department stores, which reported the sharpest decline in employment (-24.5%).

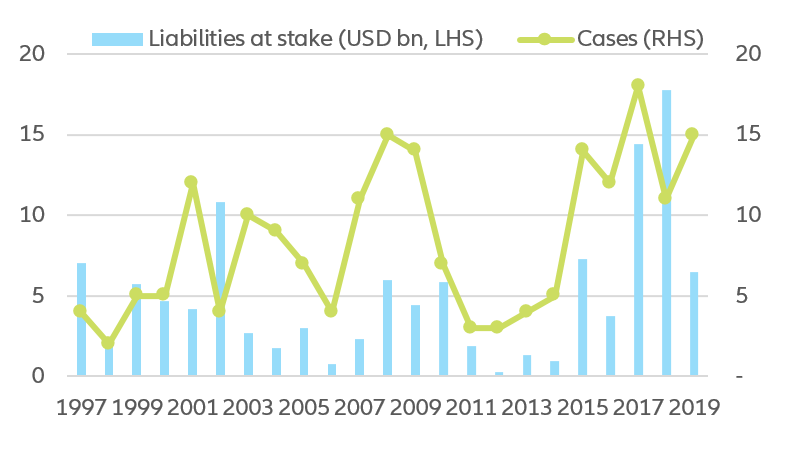

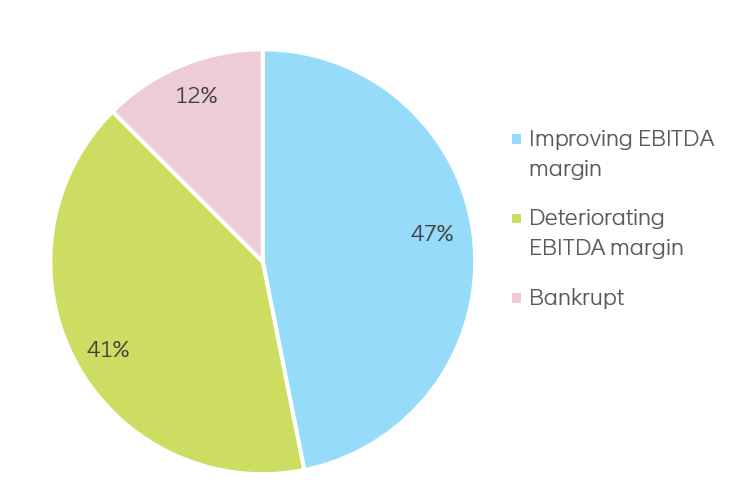

- We observe a clear surge in large retail insolvencies since 2015, involving more than USD45bn in liabilities. High-profile insolvencies are also telling of a broad erosion of profitability. Drawing on a panel of 127 U.S. corporates, we find that one in 10 listed retailers has gone bankrupt since 2008, and that another 41% have seen a decrease in profit margins, especially in the department store, discount store and clothing store sub-segments.

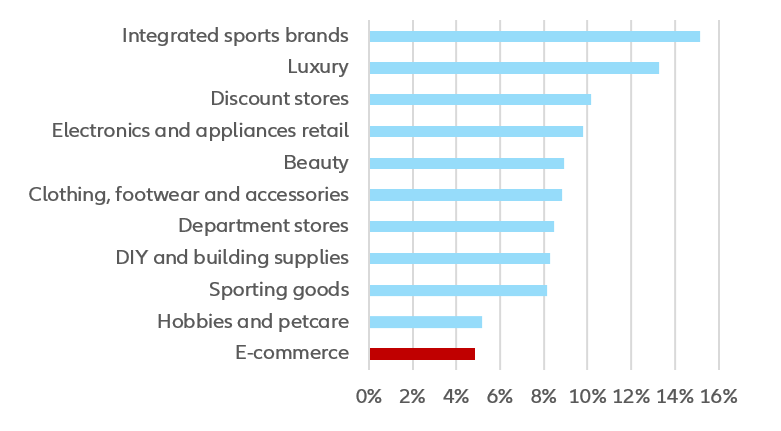

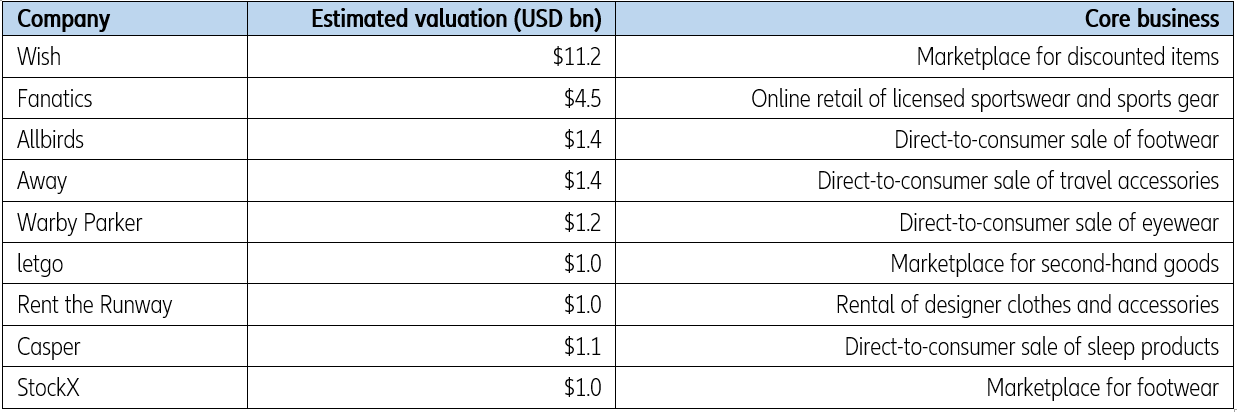

- As a “winner-take-most” business, e-commerce revolves around a limited number of companies. Leaders have a commanding share of sales, and more importantly, of profits. The shift from offline to online has had a net negative impact on company count, retail employment and profit distribution. For all its top-line growth, e-commerce displays the lowest median profit margin of all segments. The adoption of new business models also carries inherent transition risks. Moreover, e-commerce has seen few successful new entrants: Between 2008 and 2019, e-commerce accounted for only eight out of 47 newly listed retailers. New entrants display the lowest profit margins and only three of them were cash-flow positive in fiscal year 2018.

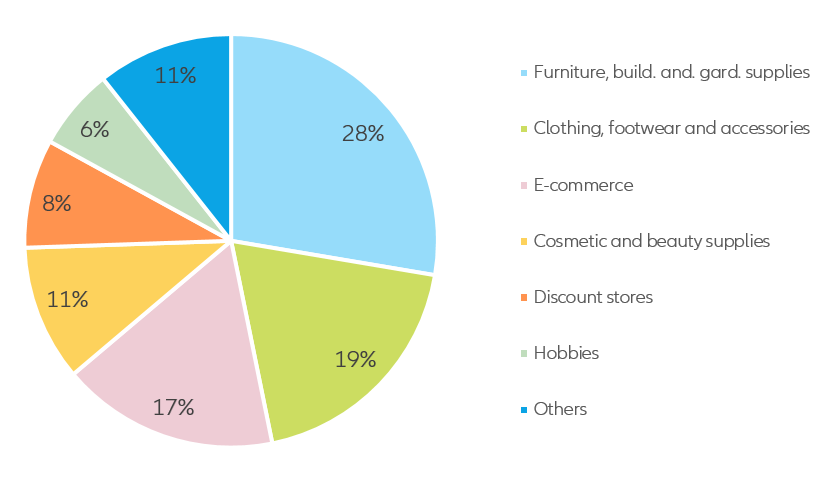

- What does this negative sum game mean for companies? We expect further e-commerce penetration and heightened competition to eliminate over 500,000 jobs and 30,000 establishments by 2025. All segments, except beauty and cosmetics, will see substantial cuts in physical retail capacities with apparel, electronics & appliances, as well as department stores, facing the biggest challenges. This would represent a significant acceleration from the pace of destruction observed over the past few years. Additional bankruptcies of large retail chains are inevitable and will be instrumental in reducing the U.S. retail footprint: We anticipate the highest default risks for large corporates in clothing, footwear & accessories stores, as well as department stores. Furniture and home furnishings stores are also likely to see a deterioration of credit metrics as competition heats up.

- For consumer goods companies supplying discretionary retailers, growing e-commerce penetration will not only translate into heightened non-payment risks, but also a further concentration of their retail mix. Retail consolidation could in turn have an adverse impact on their bargaining power and profitability. Incumbent retailers also face the threat of growing competition from their own suppliers.

Where does U.S. retail stand in the creative destruction process?

At first glance, the U.S. retail industry is the typical case of what the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter called “creative destruction”, in which new entrants capture growth or create new markets altogether at the expense of established companies. In the long run, creative destruction is supposed to have a net positive impact on the economy; however, judging from figures pointing to shrinking company count, employment and profitability, e-commerce isn’t compensating for the destruction of physical retail.

More than one in ten U.S. discretionary retail stores have closed since 2008

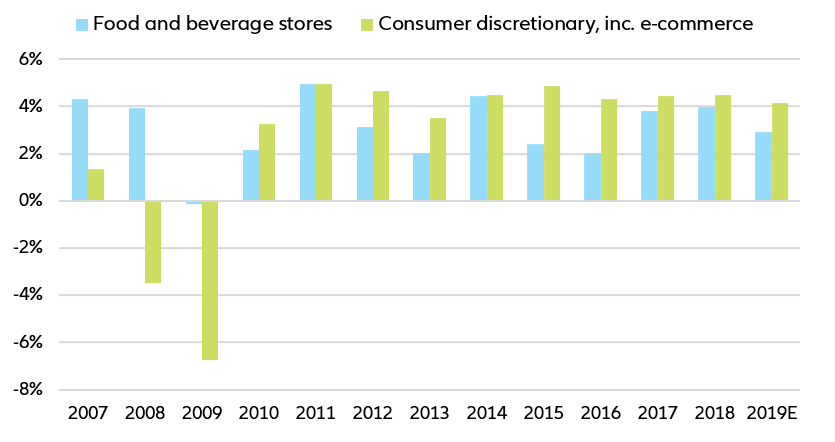

Since 2008, U.S. consumer spending on discretionary items has generally outpaced spending on food and beverages, growing at about +3.2% per annum (vs. +2.9% for food and beverages). In 2019, discretionary consumer goods generated an estimated USD1,960bn in retail sales, accounting for more than a third of the total U.S. retail market.