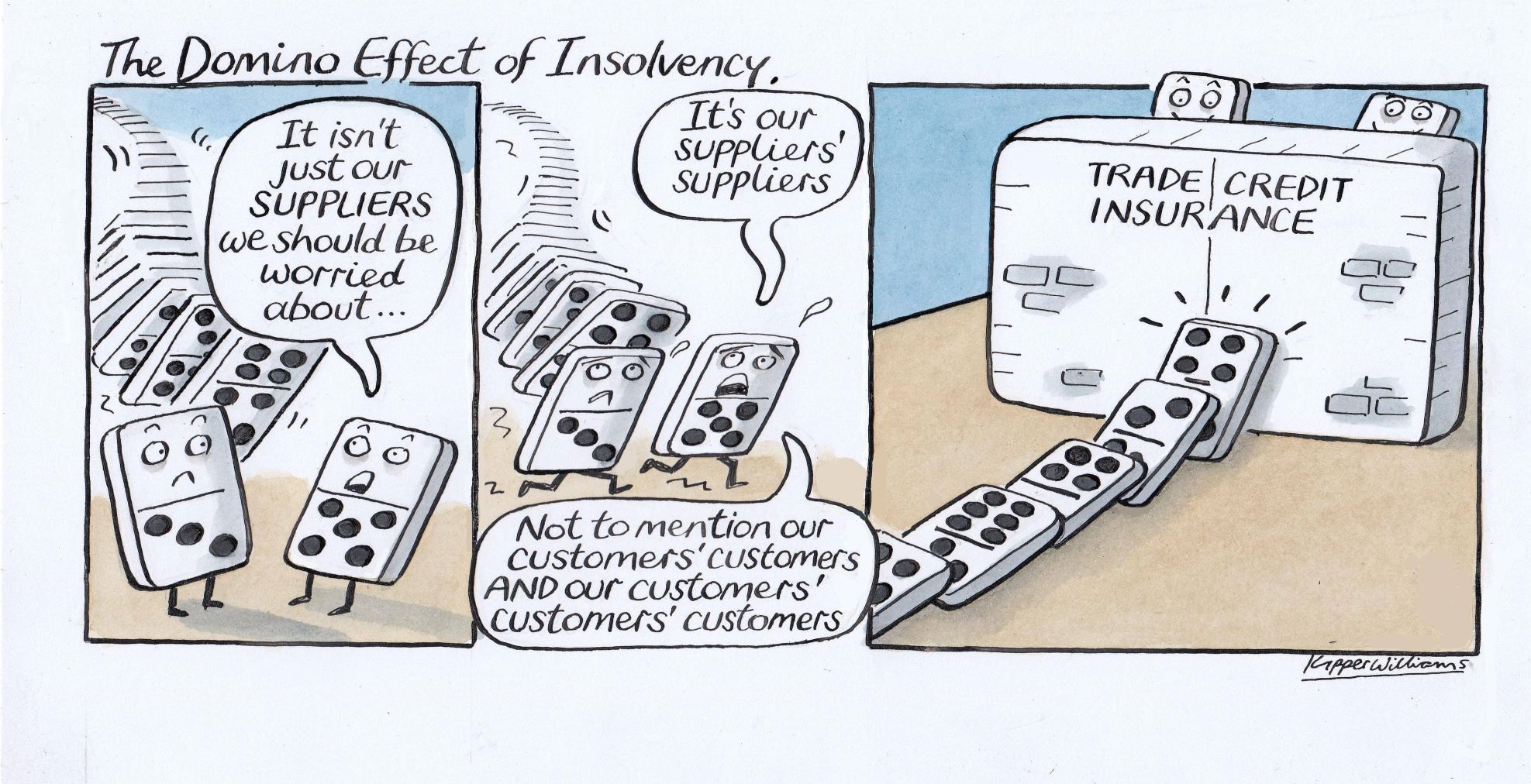

What is the domino effect of insolvency?

The domino effect of insolvencies is the chain reaction that occurs when a company — usually a customer further down your supply chain, or a supplier further up your supply chain — gets into financial difficulties and the repercussions impact your business. Sounds simple enough, doesn’t it?

It’s not.

Both the good and the bad can turn ugly.

A customer goes bust. Two obvious problems. How do you get paid? Who do you sell to now? Supplier goes bust. Where do you get your components or your raw materials? The ‘bad’ is easy to identify.

The surprising news is that it’s not just when things go badly that problems can arise; sometimes what looks to be a positive development can cause problems too. Your main competitor goes bust. Whoopee! The market is all yours now. But their local supplier also supplies you and they have been pulled down too. So now you have no local supplier. You are obliged to look further afield. That will push up transport costs. There may even be tariffs to pay, if the new supplier is overseas. And you are a new customer in an industry that has just seen a major insolvency (your competitor), so the new supplier requires payment up-front. Now you have cash-flow issues to manage. Will the bank help with finance? Well, maybe not, because your competitor’s demise has also made the banks jittery about your whole sector. You didn’t see all that coming. How could you? (Answers will follow.)

These days, supply chains are more integrated than ever and that can complicate matters. A manufacturer may have collaborated with a supplier to develop parts or materials that meet precise specifications. Probably even has the manufacturer’s logo stamped on every piece. If the customer goes bankrupt, the supplier may get left with unpaid invoices and a warehouse full of parts with no resale value. Healthy integration has suddenly become deadly entanglement.

The financial distress may not even be real. Mere rumours that a company can’t pay its bills can alter sentiment in the sector. Nor does the insolvency even have to be in your vertical. It might just be in your geographical area. If you are a restaurant and a big local employer goes bust, it doesn’t matter what business they were in; unemployed people dine out less. But it’s even worse when a region is dominated by one sector.

Which companies are at risk from the domino effect of insolvencies?

According to R3, the UK Trade Association for Insolvency and Restructuring, 26% of companies were impacted by the domino effect of a customer failure within their supply chain, during a 6-month period in 2018. And that was before Covid-19! The companies at most obvious risk from the insolvency domino effect are SMEs who operate on tight margins of money, or time, and those with all their eggs in one basket. Their cash-flow management depends disproportionately on one or two big customers. That leaves them vulnerable. Now you might pride yourself on knowing your customers but how well do you know your customers’ customers, and their customers? Or, looking to the purchases side, how well do you know your supplier’s suppliers. According to a study of the automotive industry by Deloitte, thirty times more disruptions are caused by tier 2 suppliers than tier 1 suppliers.

What are some famous examples of the domino effect of insolvency?

There have been some infamously catastrophic insolvencies. The demise of Lehman Brothers led to the global financial crash. Why? The domino effect of their insolvency. Mortgagees couldn’t pay their premiums; bank couldn’t meet its financial obligations. And when Carillion went into compulsory liquidation, it caused 75,000 job losses. But Carillion itself directly employed only a fraction of that number. The rest were victims of the domino effect. Thomas Cook’s collapse took down 500 Spanish hotels that were not owned by Thomas Cook. The Toys R Us bankruptcy in 2017 was the third largest retail bankruptcy ever. 30,000 employees lost their jobs. Major toy makers like Hasbro and Mattel received only pence on the pound for outstanding invoices. To stay in business, they had to scramble to find alternative outlets for their products. But, at least with the benefit of hindsight, most of these cases appear to have been foreseeable. But what about the imponderables?

Why it is hard to anticipate a domino effect without professional help?

Unless it is your job to gather market intelligence, you cannot possibly gauge the risks at three, four and five removes from your immediate customer/supplier relationships. Let’s say you are a big-brand fashion retailer and things are going well. Suddenly a supplier to a supplier to your wholesaler is in the headlines over a child labour scandal. Or, more precisely, YOU are in the headlines, because yours is the brand name that everybody knows. Go figure the possible consequences of all that adverse publicity.

And, as if reading a crystal ball were not difficult enough, things can happen to cloud the glass. Carillion is a case in point. There were warning signs that Carillion was in trouble. And people saw the signs. But the UK Government carried on issuing big contracts to the firm and that created a false sense of security, leading some in the supply chain to assume that Carillion was ‘too big to fail’. Nowadays, that phrase is being superseded by ‘too connected to fail’. Such is the sophistication and interdependence of modern supply chains that we could soon be talking about the kingpin effect. This would be where an insolvency wreaks havoc — not because the company is the biggest but rather because it is at the heart of many intertwined supply chain networks. Governments are looking to identify these lynchpins and consider measures to keep them operating. Sounds sensible. The trouble is that — by normal criteria — these companies might no longer be viable. The so-called ‘Zombie’ businesses are a new trap to beware of. Rather than a dodgy domino they are more like a teetering tower of Jenga.

So what can you, yourself, do to mitigate the risks to your business?

- Try to develop a balanced spread of customers. (Eggs in many baskets.)

- If your current suppliers went down, how would you secure alternative supplies?

- Be risk-aware. When talking to suppliers and customers, listen out for clues.

- Before getting involved with letters of credit, check out the pros and cons of Letters of Credit, Factoring, Self-insurance and Credit Insurance: Options for mitigating credit risk.

- Where does your product end up? Where and how are the raw materials sourced? Is there anything potentially contentious to be concerned about?

- Learn how to identify and mitigate enterprise risks: Ebook - How to future-proof your business?

- Seriously look into Trade Credit Insurance (more on this in a moment).