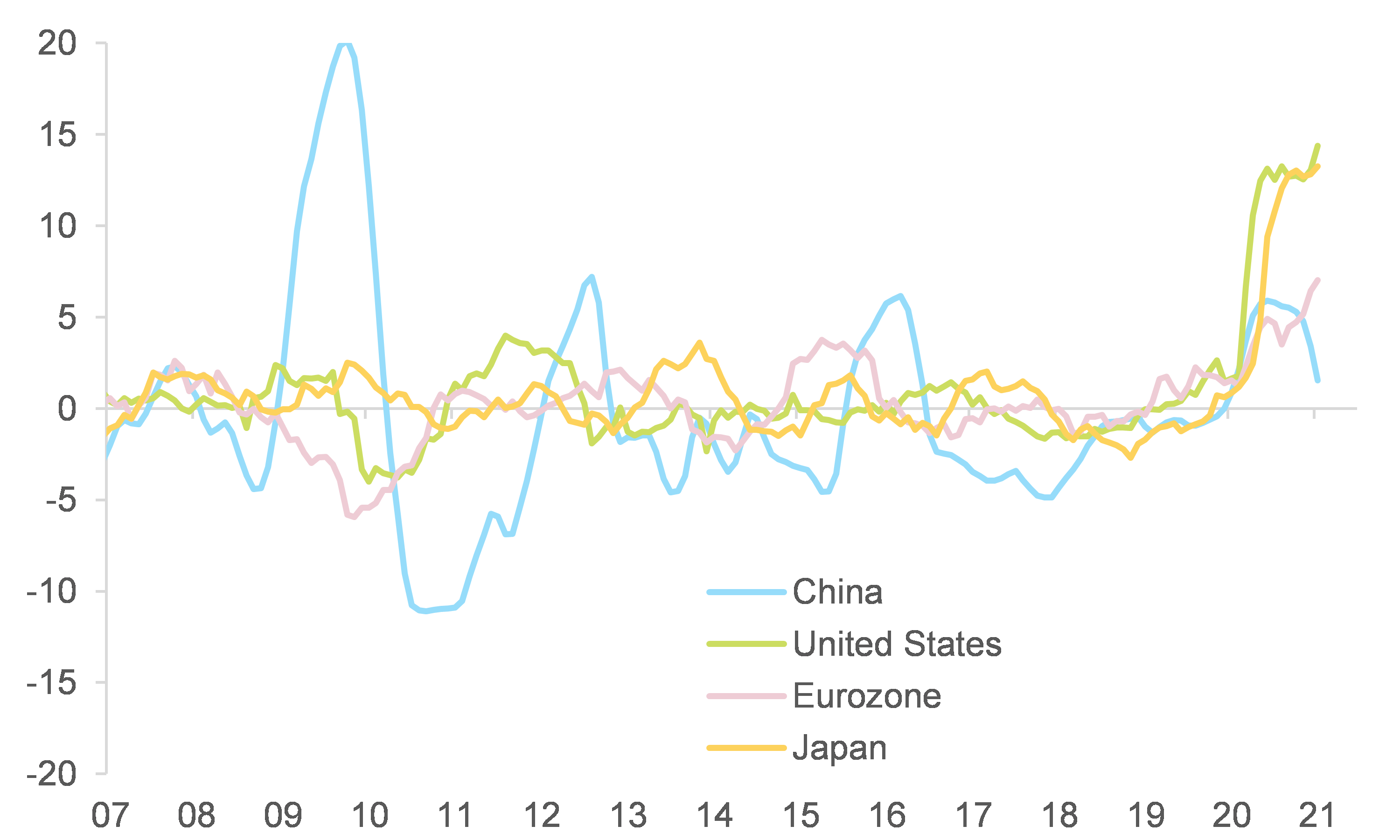

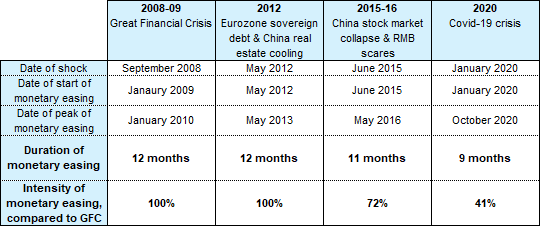

With policymakers’ focus coming back to financial stability, Chinese stimulus will not be saving the global economy this time round. But expect monetary tightening through liquidity and regulation, rather than policy rate hikes, in 2021. Authorities in China are describing the policy mix in 2021 as “proactive” on the fiscal side, and “prudent” on the monetary side. However, China’s monetary policy already started to tighten in Q4 2020, going starkly in the opposite direction compared to the world’s other major economies (see Figure 1). In fact, our proprietary credit impulse index shows that in 2020 China’s monetary easing lasted for less time than in 2008-09 (by three months) and represented only c.40% of the monetary stimulus implemented then (see Figure 2): this is slightly more than the one third we had anticipated in mid-2020 (see here for more details), but still relatively low.

Figure 1 – Proprietary monetary impulse indices