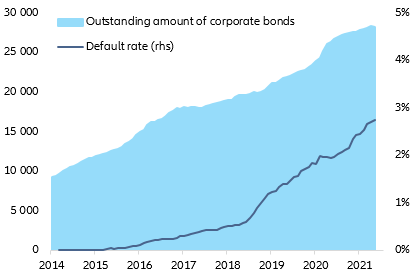

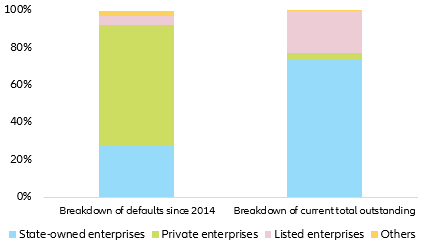

The rising defaults aren’t necessarily a bad thing. We would argue that such defaults are a healthy and necessary step for the Chinese credit market to consolidate and stabilize, leaving some necessary room for Chinese authorities to further clean up bad debt and move towards a more market-oriented manner. Consequently, we expect some exacerbated volatility in the short run but we also expect investors to be able to benefit from a healthier and more efficient environment in the mid to long run.

However, it is important to bear in mind that despite the good intentions of the Chinese government, there is a non-negligible probability that things do not go as expected. In this context, if government support turns out to be weak, it will trigger large waves of SOE bond downgrades, leading to a systematic crisis in the Chinese financial system. In our view, though, this remains a tail event. In the isolated Huarong case, the tool box is sufficient, including measures such as implicitly guiding banks to provide liquidity to Huarong or expanding further tools such as financing support in the form of a

Credit Risk Mitigation Warrant (CRMW).

Recently, Chinese authorities have finally shed some light on how they intend to deal with Huarong, indicating that they want to secure the company’s strategic role so it can continue its core business of distressed asset management, and reform it by selling non-core assets and business lines, a sign of the determination to further clean up the country’s bad debt and to guarantee financial stability. From a broader target perspective, maintaining financial stability has been and remains the utmost priority for the Chinese government, which certainly has a strong wish and the necessary tools (eg. high level of FX reserves and manageable level of public debt, mostly domestically-owned) to prevent any increase in systemic risk. This is even reinforced by the fact that in the past few years, financial watchdogs have gained experience in dealing with different types of credit failures, including taking over financial institutions such as Baoshang Bank.

In this regard, we believe that Chinese top authorities could seize the opportunity of the Huarong failure to come up with a plan to deal with similar future challenges. This is of particular interest since on the one hand, Chinese authorities regard breaking the implicit guarantee and implicitly forcing SOEs to responsibly operate their businesses as critical for the long-term healthy development of credit markets. On the other hand, they do need to manage investor fears so that negative market sentiment itself does not lead to any structural financial market instability. As a result, to find and maintain the balance between debt cleanup and market stability will be a challenge for Chinese authorities to overcome and for investors to monitor. But we remain positive that they will manage, as indicated by the latest developments.

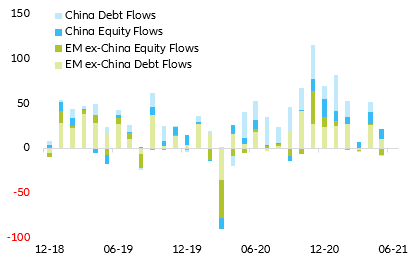

What does this mean for investors? Firstly, we believe that with a mid- to long-term investment horizon, the risk-return reward of Chinese credit remains highly attractive. This is particularly the case, as previously said, since the Chinese fixed income market is a trillion-dollar-plus market that has an average BBB rating, with more than ~3% yield compensation in both local and hard currency terms. This when compared to other relevant EM markets remains highly attractive, especially given the current low-yield environment.

Secondly, the favorable macroeconomic environment, the large and steady local investor base, a rather stable FX rate and a determined government body certainly speak to the intrinsic value behind the economic attractiveness of China.

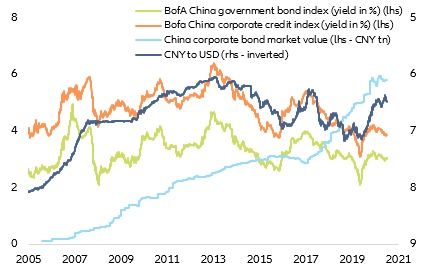

The quick rebound from the Covid-19 crisis is testament to this strength: the Chinese economy was already operating at c.75% of usual levels one month after containment measures were put in place in January 2020 , and this earlier recovery has allowed it to win export market share since the beginning of the crisis (23% on average in 2020-21 vs. 19% on average over 2017-19). This quick economic rebound (GDP grew by +2.3% in 2020 while it contracted in most other major economies) allowed Chinese authorities to start tightening the policy mix as soon as Q4 2020, ahead of the global trend. All this ensured a strong performance of the CNY in 2020, with 6.5% appreciation against the USD and 3.7% appreciation against a basket of currencies (CFETS RMB Index) over the year.

Going forward, even though China’s recovery still needs to broaden – notably regarding household consumption – we expect the economy to post solid rates of growth in 2021 (+8.2%) and 2022 (+5.4%). This means that on the policy side, authorities can continue to focus on managing long-term vulnerabilities (eg. in the real estate and financial markets) instead of only short-term economic support. We expect the USDCNY rate at 6.3 at year-end (vs. 6.5 at 2020-end).

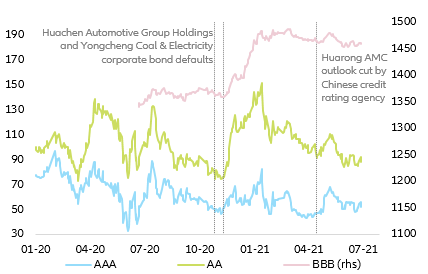

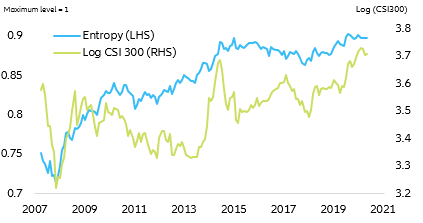

Thirdly, China has an ambitious long-term plan for structural reforms in order to ensure a smooth transition to lower potential growth as the economy matures . Part of the “dual circulation” strategy that was first introduced in May 2020 is capital account liberalization and renminbi internationalization. To that end, efforts for Chinese equities and bonds to be more market-driven and reforms to ease foreign investors’ access to China’s capital markets will continue. Allowing unperforming SOEs to default removes the perception of implicit guarantees from the government that allows for moral hazard. The latest acceleration of credit downgrades (~375 rating downgrades until April 2021 compared to and average ~100 rating downgrades per year during the previous three years) will slowly bring more transparency to the market and gradually but steadily allow a re-pricing of “real”

credit risk without spooking investors.

Last but not least, China has a firm commitment to accelerate the development of a green and low-carbon circular economic development system. In Febuary 2021, the State Council, China's cabinet, released guidelines that target peak carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. Such commitment is also a step in the right direction that matters to all investors.

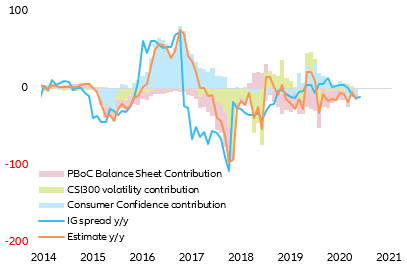

From a carry perspective, it all sounds good. But is the Chinese credit market expensive? Trying to disentangle the drivers behind credit spread moves within the Chinese credit market is more difficult than in other markets. This is especially the case as credit spreads currently contain an implied put protection due to their SOE concentration, making it difficult to disentangle the pure monetary policy effect from their intrinsic governmental put protection. This is the case even considering the latest SOE defaults.

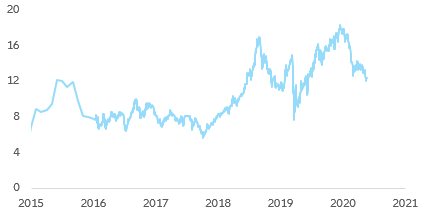

Nonetheless, our proprietary model shows that the combination of slowly disappearing monetary and policy support, combined with depressed equity market volatility and somehow stable but increasing consumer confidence, have managed to keep investment grade credit spreads stable at 80 to 90 bps, which from a historical perspective is extremely tight. However, even if from a historical perspective spreads remain extremely narrow, we do not have many reasons to believe that this situation is prone to a quick change in 2021 (Figure 7).

Figure 7: China IG spreads decomposition (y/y change - bps)