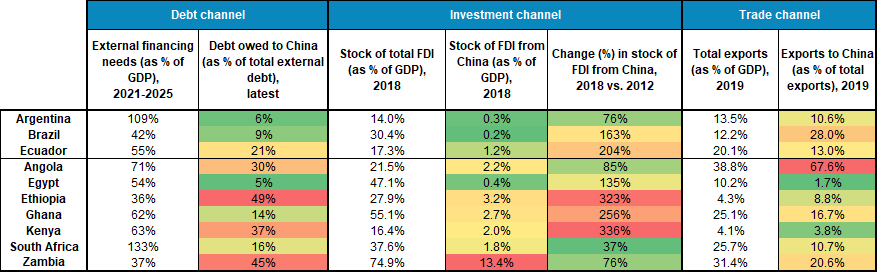

China played a crucial role in the global economic recovery after the 2008-09 financial crisis, but the post Covid-19 recovery will be different: We expect China to slow its international engagement over the next few years. In this context, Angola, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ecuador and Ghana, along with Brazil and South Africa, could struggle to find alternative international sources for funding, investment and trade to sustain their economic growth. The Chinese economy is likely to experience profound changes in the medium to long run, with a shift in the country’s priorities (dual circulation strategy), the slowdown of economic growth and a heavy domestic debt burden (see our recent report for more details). As a result, we expect China’s role as the global growth driver to recede in the coming years. To identify what this could mean for low- and middle-income countries, we look at three different channels of impact: debt, investment and trade.

Figure 1 – Vulnerability to China turning inwards via the debt, investment and trade channels

Figure 1 – Vulnerability to China turning inwards via the debt, investment and trade channels