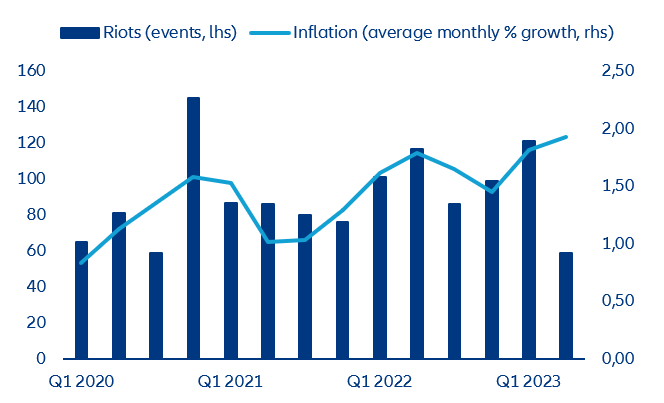

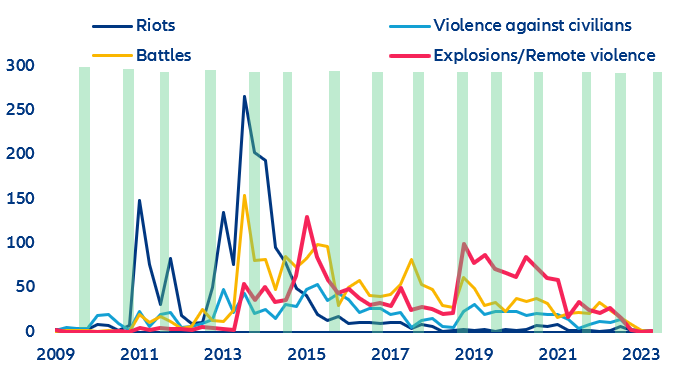

The frequency of political-related events in the last quarters suggests that restrictions on public space have been extended beyond Ramadan, when confrontations historically tend to calm down (Figure 14). Since mid-2018, Egypt’s civil society has been de facto silenced and it is unclear whether this will lead to any resounding developments in the short term. The last time the calm lasted so long was in 2009-2010, i.e., before the Arab Spring erupted. Riots occurred often between 2011 and June 2014 (when al-Sisi's presidency began). In contrast, in the year before he came to power and ever since, explosive attacks and border and insurgent clashes have been by far the most recurring event, unusual for a country not involved in open conflicts. What is surprising about the past six months is the neutralization of any public action, be it a small sit-in or a militia clash. On the other hand, the escalation of the conflict in Sudan, sporadic Islamic State attacks on the Sinai Peninsula in the first half of 2023 and Israel recently complaining about the porousness of Egypt’s borders all point towards increased instability and limited military capability.

The distance between the establishment and the rest of the Egyptian population has also increased, although generalized unrest remains unlikely in the short term and progress towards IMF-inspired reforms is faltering. The IMF wants to ensure that conditional funds will effectively redress imbalances. Reforming the economy will require redesigning the role of the military and downsizing megaprojects (e.g. the new administrative capital 30km outside the overcrowded and increasingly impoverished Cairo) that are propping up the construction sector, which employs 13.8% of the labor force – the third sector in Egypt behind agriculture and trade, and second in terms of male workers. However, there is little incentive to pursue additional reforms with the upcoming presidential election in February 2024 and evolving bilateral relations with the Global South. For example, India is set to acquire a dedicated land area for national industries in the Suez Canal Economic Zone and build a USD12bn green hydrogen plant. Since its completion 154 years ago, the Suez Canal has been used as a strategic trump card by successive governments. Several sources talk openly about the possibility of leasing it. Transit fees were already raised several times in 2022-2023 and shipping brokers agree that there is still room for an increase without significant consequences on traffic volumes, given its competitive advantage over alternative routes.

The combination of silenced dissent and increasing mistrust towards international lenders leaves the door open for different outcomes, while another Egyptian pound (EGP) devaluation appears imminent. The differential between the nominal value of the EGP and its fair value is reaching another peak following those of late 2022 and early 2023. With several other countries on the continent devaluing their national currencies inter alia to attract investors, this could be the Egyptian government's next move, hoping the status quo holds up.

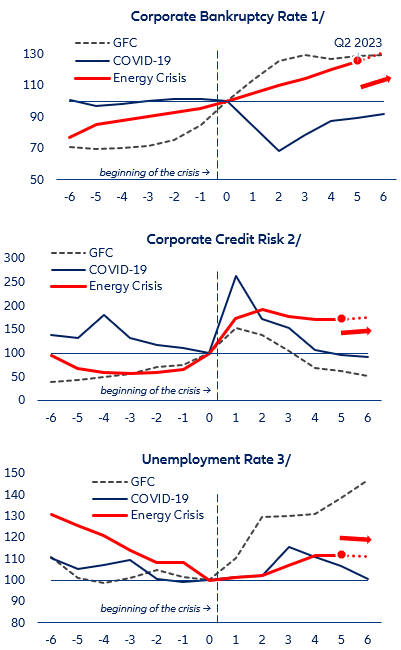

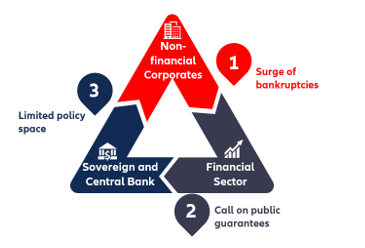

Unlike the sovereign debt crises, an escalation of social tensions could have a contagion effect on several African countries, also given the uncertainties about the role of Wagner paramilitary in the area and increasing insecurity. While all eyes have been on the state of African governments' accounts and the risk of transmitting sovereign crises for months, the main risk to the continent may instead lie in social risk. No other sovereign defaults have emerged at the time of writing since Ghana's deafening crisis in December 2022, although public finances have been deteriorating in Egypt and Tunisia in particular. Several African governments are looking for their own way out with lenders (concessional lenders, China, former colonial powers, other African governments). Three years after a currency crisis, real GDP is typically between 2-6pps lower than where it should be based on long-term growth. In most cases, however, output losses start materializing before the currency collapse takes place. In fact, it turns out that the collapse of the currency itself boosts production. Previous research shows that output growth slows down in the year leading up to currency devaluation and during the same year. However, the likelihood of a positive growth rate in the year of the collapse is over two times more likely than a contraction, positive growth rates in the years that follow currency collapse are likely and the persistence of the crash matters. Instead, it will be the responsiveness of individual economies and the resilience of the social contract that will tell whether a cost-of-living crisis will also bring social disruption across the region.

![Figure 1: Loans to households for house purchases (monthly flows) [left] and overall trend [right]](/en_global/news-insights/economic-insights/Eurozone-doom-loop/_jcr_content/root/parsys/wrapper_copy_copy_co/wrapper/wrapper_copy_copy_co/wrapper/image.img.82.3360.png/1689178807894/13072023-figure1.png)

![Figure 15: Liabilities of private non-financial corporations [top] and sovereign exposure to private non-financial corporate debt via guarantees and central bank asset purchases [bottom] (% of GDP)](/en_global/news-insights/economic-insights/Eurozone-doom-loop/_jcr_content/root/parsys/wrapper_copy_copy_co/wrapper/wrapper_copy_copy_co_1730082260/wrapper/image.img.82.3360.png/1689180664423/13072023-figure15.png)

![Figure 18: Eurozone – first order Impact on banks (net losses equivalent to number of years of profits) [top] and governments (higher fiscal deficit from contingent liabilities, central bank exposures and lost taxes as % of GDP) [bottom]](/en_global/news-insights/economic-insights/Eurozone-doom-loop/_jcr_content/root/parsys/wrapper_copy_copy_co/wrapper/wrapper_copy_copy_co_551694921/wrapper/image.img.82.3360.png/1689180979850/13072023-figure18.png)