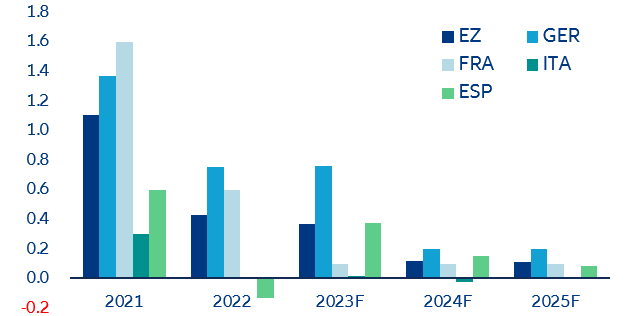

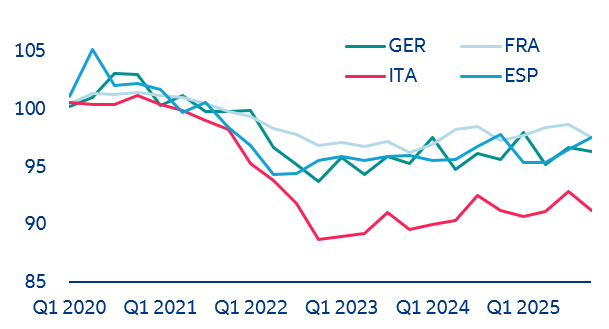

Germany is pursuing fiscal consolidation through a strict budget course in the coming years – but it could be disrupted by a shadow budget. German fiscal policy will remain much more supportive than the pre-pandemic period. Due to the current cyclical and structural headwinds, the call for fiscal stimulus is high and the government announced an economic package worth EUR32bn of corporate tax cuts – spread over four years and probably financed by budget cuts rather than increased spending. Clarifying the fiscal outlook is thus challenging as many budget questions remain open.

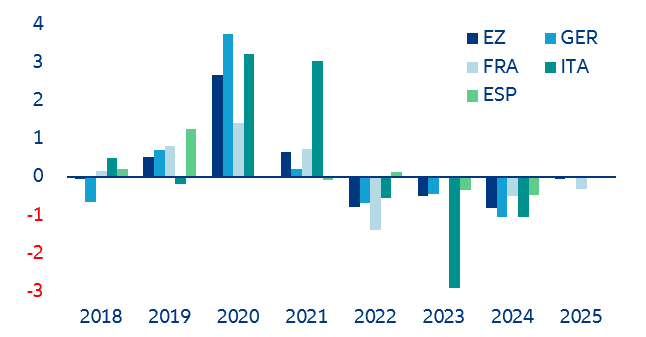

A large share of fiscal action in recent years has been in off-budget spending, and it will probably continue to do so. Despite record spending, the federal government is in a bind. The desires of the government coalition are too high and thus borrowing is much higher than officially stated. To comply with the debt brake anchored in the basic law (“Grundgesetz”), net borrowing is only possible to a very limited extent. According to the draft, new debt should be EUR16.6mn in 2024, which is around EUR30mn less than in 2023. Fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP will improve from -3.7% in 2023 to -1.9% in 2024. While the budget deficit is expected to drop from 2.6% of GDP in 2022 to around 2.25% in 2023, 1.25% in 2024 and even 1% in 2025, mainly due to a reduction in spending on pandemic- and energy-crisis related support.

Overall, Germany's fiscal policy is expected to remain looser than before the pandemic, with a budget deficit projected for 2025 compared to a surplus in the years leading up to 2019. While the structural primary budget is likely to turn positive again in 2025, the surplus will be smaller than pre-pandemic levels. This balanced fiscal stance seems reasonable, considering Germany's current inflation levels and tight labor market, as well as the recognition that its pre-pandemic fiscal policy may have been too restrictive and contributed to below-target inflation.

However, due to federal special funds outside of the federal budget, such as for the Bundeswehr or the climate and transformation fund, real government spending in 2024 will be around EUR540bn instead of the officially stated EUR445.7bn. In addition, the government had already booked almost EUR90bn into the budget when the debt brake was temporarily suspended. The special funds have been criticized as they interfere with Parliament’s budget law. In addition, it would be more accurate to speak of “special debts” as debts and spending programs worth billions are hidden in there. The official path to fiscal consolidation in Germany is thus undermined by a shadow budget.

Meanwhile, France is kickstarting a modest fiscal consolidation amid a challenging macroeconomic backdrop. The French government is set to unveil its 2024 budget bill on 27 September. The Ministry of Finance is floating around EUR16bn of savings (around 0.6% of GDP) to target a fiscal deficit of -4.4% of GDP after -4.9% in 2023. It has already announced that it will forecast real GDP growth at +1.4% in 2024, a -0.2pp downgrade compared to its previous vintage. Nevertheless, the government’s real GDP growth still looks optimistic relative to the consensus forecasts (+0.8%; Allianz: +0.7%). The -4.4% deficit target may thus be difficult to achieve amid lower tax collections.

Tax revenues since the beginning of the year have already been weak amid falling VAT collections. They could undershoot next year because of weakening social contributions amid much slower job creation. The bulk of savings the government will count on will come from the phasing out of the tariff shield and other energy subsidies – this should bring around EUR10bn of lower spending relative to 2023. Besides these ‘’automatic’’ spending cuts as the energy crisis subsides, the government is looking for savings on health and labor market spending (potentially EUR1.7bn of savings on the latter).

On the revenue side, the government plans to hike or create new taxes to fund the green transition, such as a tax on flights departing from France. Housing policy is also expected to be tightened: For instance, the ‘’Pinel’’ tax credit (subsidizing investment in new housing for leasing) may be removed while the scope of ‘’zero interest rate’’ housing loan subsidy could be reduced. Against this backdrop, the government announced it will raise tax brackets in line with inflation to avoid an increase in the effective income tax rate for taxpayers (a long-lasting pledge of President Macron). This will mean a substantial EUR6bn of foregone revenues for the state. In all, we expect the government to miss its deficit target of -4.4% of GDP (we expect -4.6%) but broadly to stick to its consolidation plans despite lacking a majority in Parliament.

In Italy, tax credit expenses have added clouds to the fiscal outlook. Though the high inflation environment has helped to reduce the public debt ratio in the last couple of years (-10.5pps to 144.4% in 2022) via a higher denominator and a boost to government revenues, fiscal balances have not significantly improved since the massive stretch made during the pandemic and continued throughout the energy crisis. In Italy, a generous tax credit scheme (see Italy’s superbonus – housing boom and bust) has generated expenses larger than initially expected, also producing downward revisions to the 2021-22 fiscal deficits.

The government will submit the update to the 2023 budget on 27 September and soon after that the new fiscal targets for the next years. Though we expect some consolidation efforts, also in light of the likely reintroduction of the Stability and Growth Pact in 2024, the government will be stretched to cover unplanned costs as well as to meet electoral pledges (i.e. the tax wedge cut). Latest official estimates published in June foreseen a government deficit of 4.5% in 2023 and 3.7% next year (compared to our forecast of -5% and -3.8%, respectively) but higher financing needs (linked mainly to the tax credit, the revaluation of pensions and the delayed payment of the third instalment of NGEU funds) are not being compensated by the still higher revenues boosted by inflation. Moreover, economic activity has been slowing down.

Finally, interest payments will challenge further the fiscal position as the debt burden is gradually increasing as higher rates will kick-in on the debt that has to be rolled over. After a decade of a declining trend, we estimate that the interest payments to GDP will stay close to 4% in the coming years.

Spain has a good fiscal consolidation plan but its effectiveness remains to be seen. Whatever the outcome of the general election in July 2023, the need to address public finances will be unavoidable, limiting any attempt to pursue a more expansionary fiscal policy. Indeed, the 2023-2026 stability program presented by the government proposes a gradual reduction in the budget deficit, driven by the recovery of the Spanish economy from 4.8% of GDP in 2022 to 3.9% in 2023 and 2.5% in 2026.

While the economic recovery in 2021-2022 and rising inflation as a result of the energy crisis have helped improve the deficit and debt ratios, the next Spanish government will need to take further action in the future. While a left-wing government would likely raise taxes, a right-wing alliance would likely focus on cost-cutting. It should be noted that the fiscal effort over the next few years is likely to be significant, given the pressure from the pension reform that came into effect this year, which links pensions to the previous year's inflation index. The IMF estimates that this reform could add 3.2-3.5% to pension expenditure by 2050, on top of the 1pp increase due to population aging. As part of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRPP), the European Commission has asked the Spanish government to reintroduce an adjustment factor that would adapt initial pension benefits to changes in life expectancy and the intergenerational equity mechanism. Failure to adopt these measures would reduce future tranches of EU recovery funds allocated to Spain, which is one of the main beneficiaries of the mechanism. We expect the budget deficit to average 4% of GDP in 2023-2026 and the gross debt to improve slowly from 112% of GDP in 2022 to 108% of GDP in 2026.

Eurozone governments and institutions have been working on setting the ground rules to return to a more advisable application of the EU fiscal framework, envisaged for 2024. Negotiations are still ongoing but it is clear that some form of discipline will be needed, also to not erode all the monetary policy efforts made so far. The negotiations have focused on more flexible and tailored rules to avoid harming countries’ economic growth and to avoid procyclical rules, as well to stimulate green investment and the green transition. Though it is urgent, we expect a political agreement will be very challenging to reach. But we believe countries will make their best efforts in the coming months, a must to ensure their debt-reduction paths will be sustainable and credible in the medium term.