Additionally, heat-affected employees reduce their working hours and experience work slowdowns and make errors. Reduced labor productivity as a result of extreme temperatures is a well-documented phenomenon. The negative effects are more pronounced in poor countries which often have higher exposure (e.g., Africa, South Asia) and vulnerability (e.g., housing quality, air conditioning). The decisive factor for productivity losses is the number of days with extreme heat (typical measure: days above 90°F/32°C). According to Foster, Smallcombe, Hodder et al., the capacity to perform physical work dips by approximately 40% when temperatures hit 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Furthermore, when temperatures soar to 100°F/38°C, the decline in productivity is even more dramatic, plummeting by two thirds. Behrer, Park, Wagner et al, using US wealth data, claim that hotter temperature can reduce labor productivity, work hours, and labor income. They find that one additional day >32 °C (90 °F) lowers the annual payroll by 0.04%, equal to 2.1% of average weekly earnings. They also find smaller impacts of heat in regions with higher average wealth. These effects are due to a combination of reductions in labor supply, labor productivity, labor demand and an increase in firm costs. The estimates, which consider annual temperature fluctuations, account for intra-year adaptations such as inter-temporal labor substitution. This adaptation occurs when workers and companies try to compensate for productivity lost during a hot day or week by catching up during a cooler period within the same year. However, trying to explicitly quantify the effects of low temperatures on the payroll did not show significant impacts.

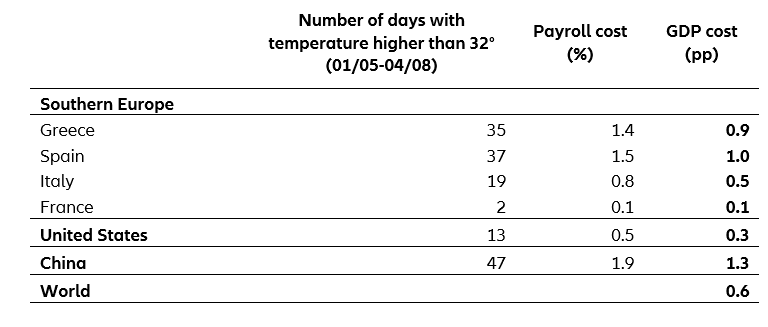

Using a first approximation, we estimate the impact of this year’s heatwave on GDP in the United States, Southern Europe, and China. Based on elasticities from the two academic articles above, we ran a ‘back of the envelope’ calculation of the consequences of the recent heatwaves. In all humility, this first-order estimate comes with several strong assumptions:

(i) temperature data is not final and we limited ourselves in scope to six countries; (ii) we used daily country averages instead of grid cell data; (iii) the elasticities for payroll impacts were calibrated on US county-level data, and payroll to GDP sensitivity was taken as two-thirds; and (iv) other channels of impact such as agricultural productivity were not taken into account.

Results show that China, Spain and Greece may have lost close to a point of GDP from the current heatwave, while Italy’s loss is closer to half a point, the US lost to a third of a point and that of France is negligible (0.1pp). All in all, using weights in global GDP, the heatwave’s toll is close to 0.6pp of GDP growth for 2023 which is important and highlights the burden of physical climate risk.