It is too soon to tell the long-term effects of the Covid-19 crisis on inequality in Latin America, but income and labor markets already seem to be Patient Zero. The pandemic has exacerbated the existing structural inequalities in Latin America’s labor markets, including a very high skill premium in terms of wages; a high correlation between the ability to work remotely and education, hence with pre-pandemic income; a very high ratio of the minimum wage to the mean or median wage, which indicates a larger share of economically vulnerable workers, and the predominance of the informal sector, whose workers have no access to furlough schemes or unemployment insurance. In this context, job and income losses hit the lower-skilled and uneducated workers the hardest. In addition, preexisting occupational differences in terms of gender and age have translated into greater disparities and future vulnerabilities as the burden of additional housework and care responsibilities fell on women. As a result, the earnings gap is set to grow further.

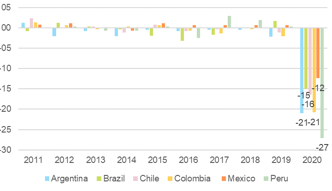

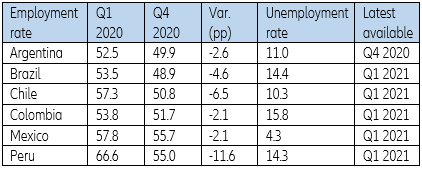

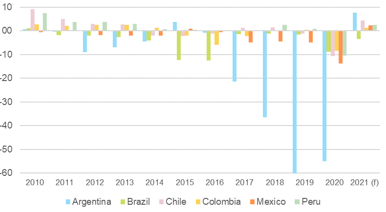

Figure 1 demonstrates the sharp decrease of total weekly hours worked to population, a measure of labor force dynamics, in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru. The largest contraction in 2020 was seen in Peru (-27% y/y), while Argentina and Colombia both recorded a decline of -21% y/y. Mexico saw a sharp decrease of -12% y/y after six years of positive growth. In terms of the rate of employment, the story is similar: Peru had almost 12pp decrease, while in Chile the employment rate was -6.5pp lower and in Brazil -4.6pp lower.

Figure 1: Growth of ratio of total weekly hours worked to population (aged 15-64), growth in %

Figure 1 demonstrates the sharp decrease of total weekly hours worked to population, a measure of labor force dynamics, in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru. The largest contraction in 2020 was seen in Peru (-27% y/y), while Argentina and Colombia both recorded a decline of -21% y/y. Mexico saw a sharp decrease of -12% y/y after six years of positive growth. In terms of the rate of employment, the story is similar: Peru had almost 12pp decrease, while in Chile the employment rate was -6.5pp lower and in Brazil -4.6pp lower.

Figure 1: Growth of ratio of total weekly hours worked to population (aged 15-64), growth in %