Covid-19 will upend the old pecking order in the global economy – and in climate policy. China is not only leading the economic recovery post-Covid-19 but also seems to be shifting from laggard to leader in climate policy, with President Xi Jinping’s pledge for net-zero emissions by 2060. The EU, too, raised its climate targets significantly in the framework of its “Green Deal” and underpinned them with its bold EU Recovery Fund. As for the U.S., the upcoming elections could be a turning point when it comes to climate leadership.

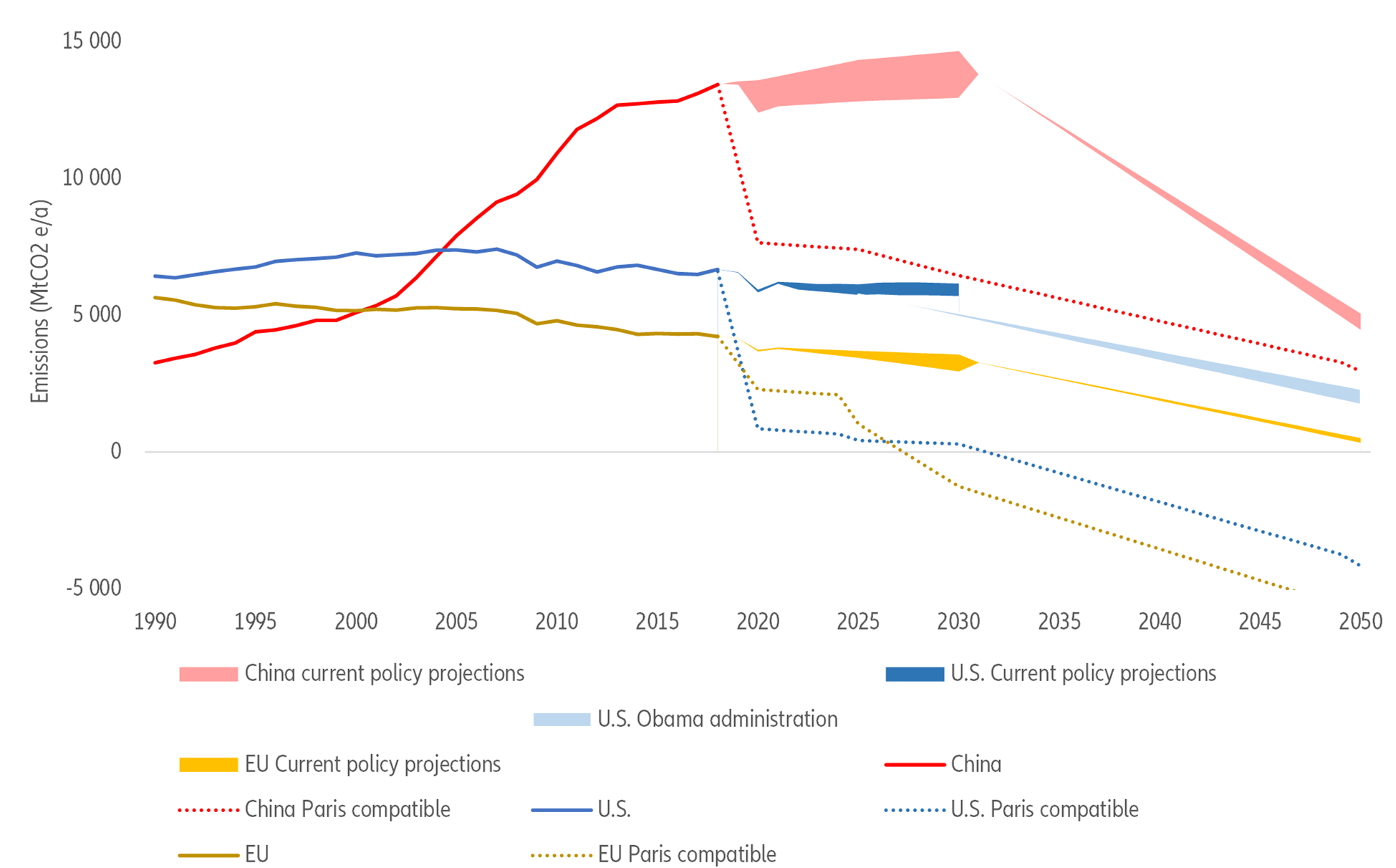

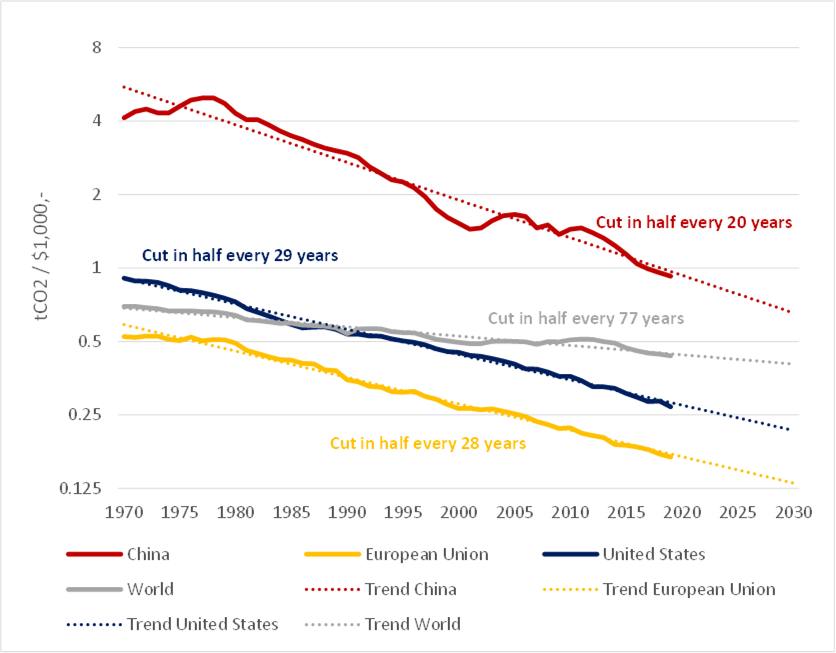

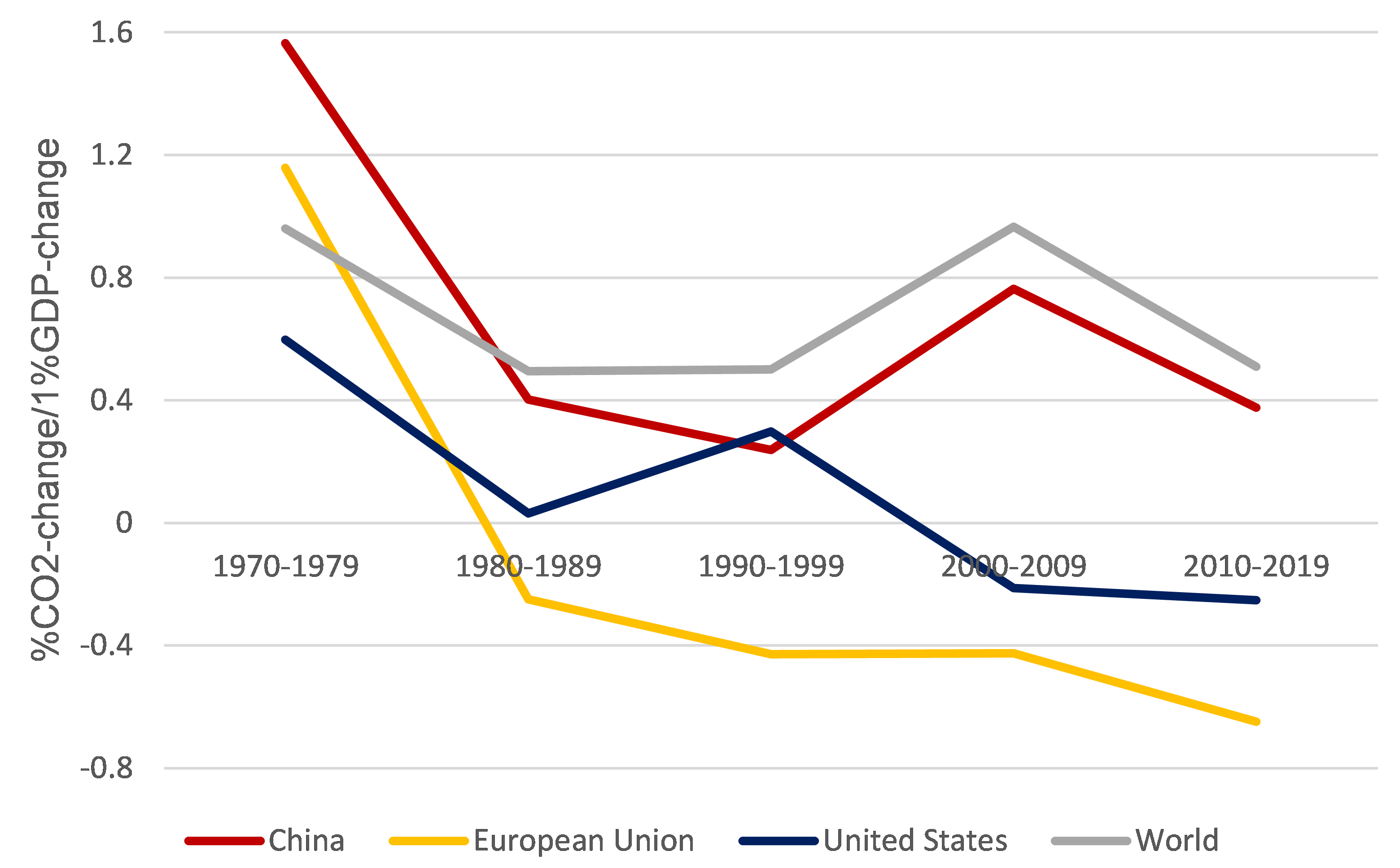

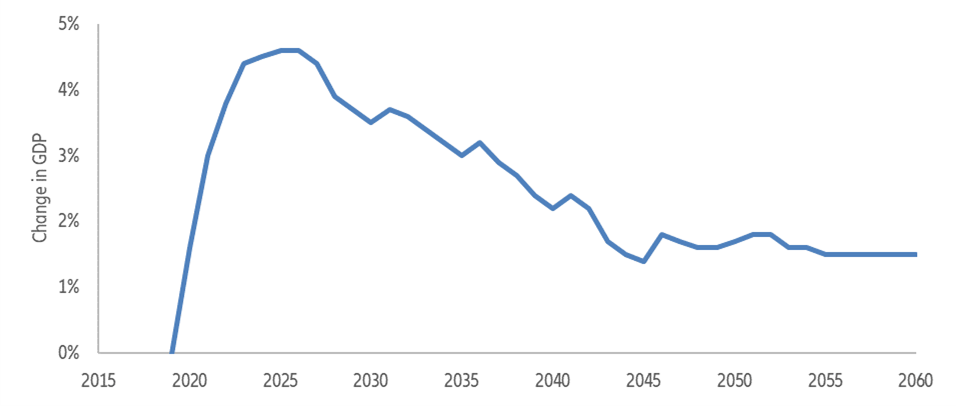

This gearing up of climate policy is welcome – and overdue. Decoupling economic growth from emissions growth isn’t enough. Based on today’s policies, the EU, China and the U.S.’s emissions combined will grow to 23.6 billion tonnes of CO2 in 2030, far above the 5.5 billion tonnes that would be compliant with Paris Climate Agreement goals. Their combined shortfall of 18.1 billion tonnes of emission reductions is equal to 50% of 2018 global emissions. Emission intensity as measured by CO2 emissions per dollar of GDP has been cut in half every 20 years in China, every 29 years in the U.S. and every 28 years in the EU. Our analysis reveals that this trend has been astonishingly robust for the past 50 years. Following these trends, zero emissions will never be reached.

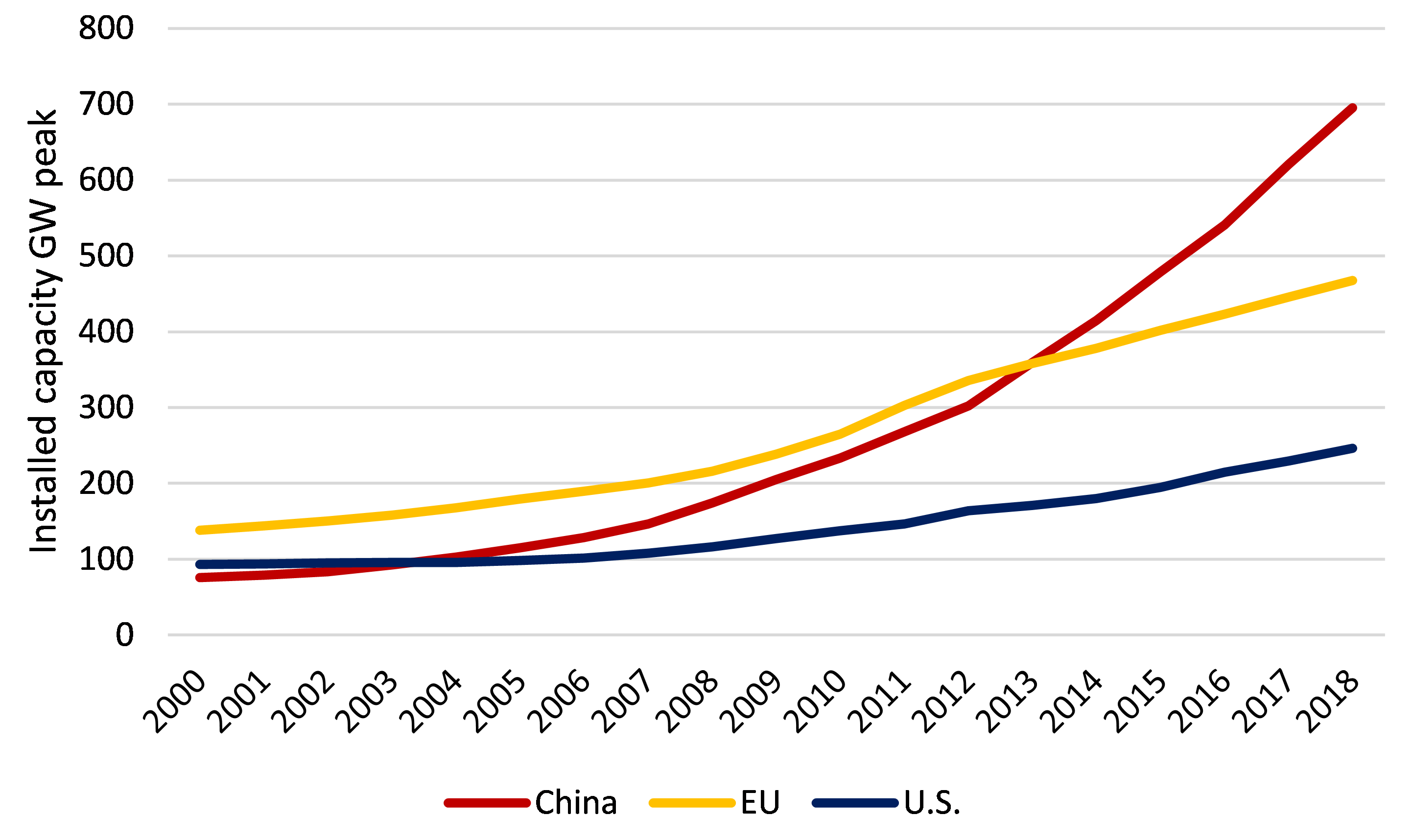

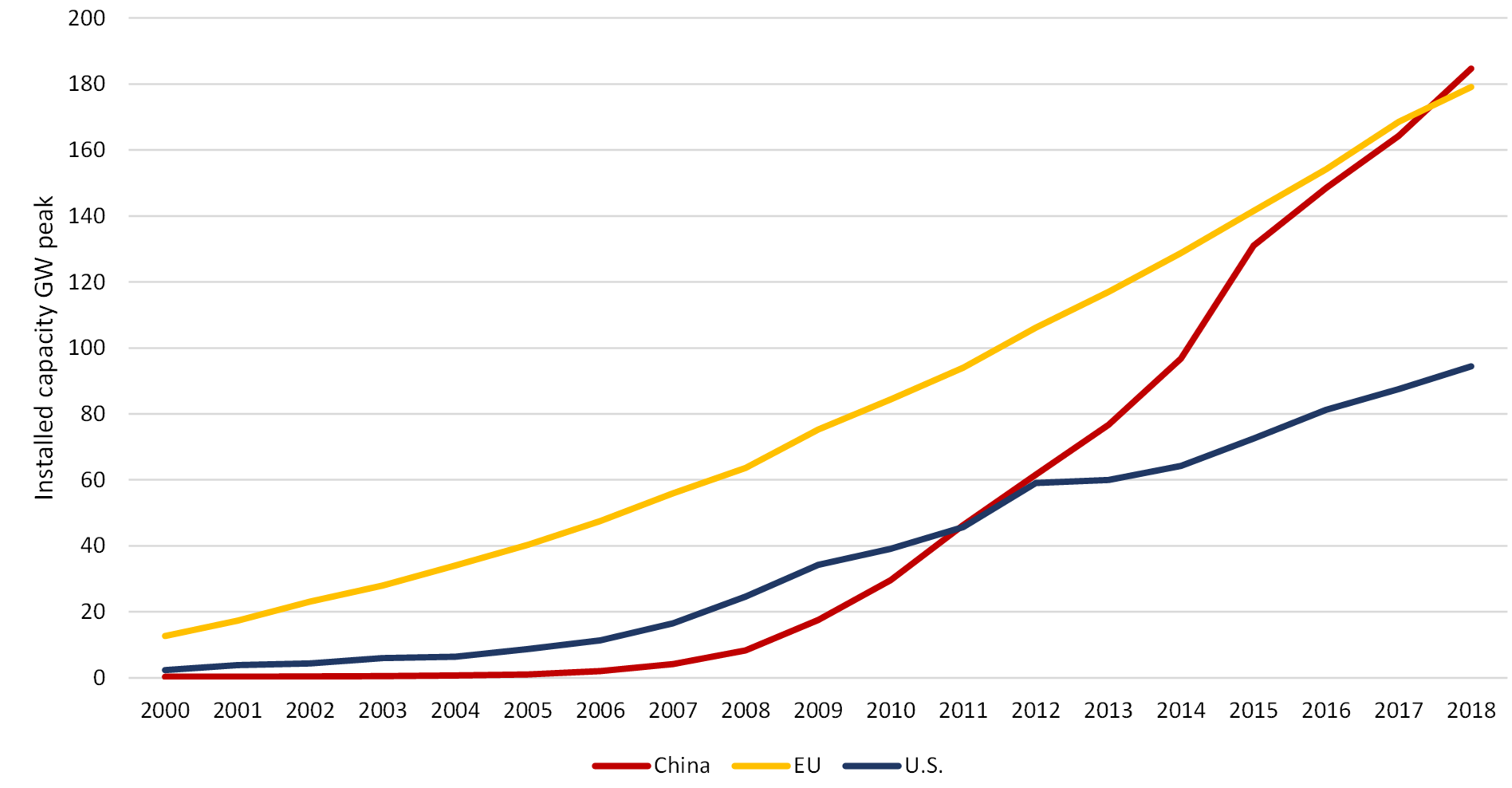

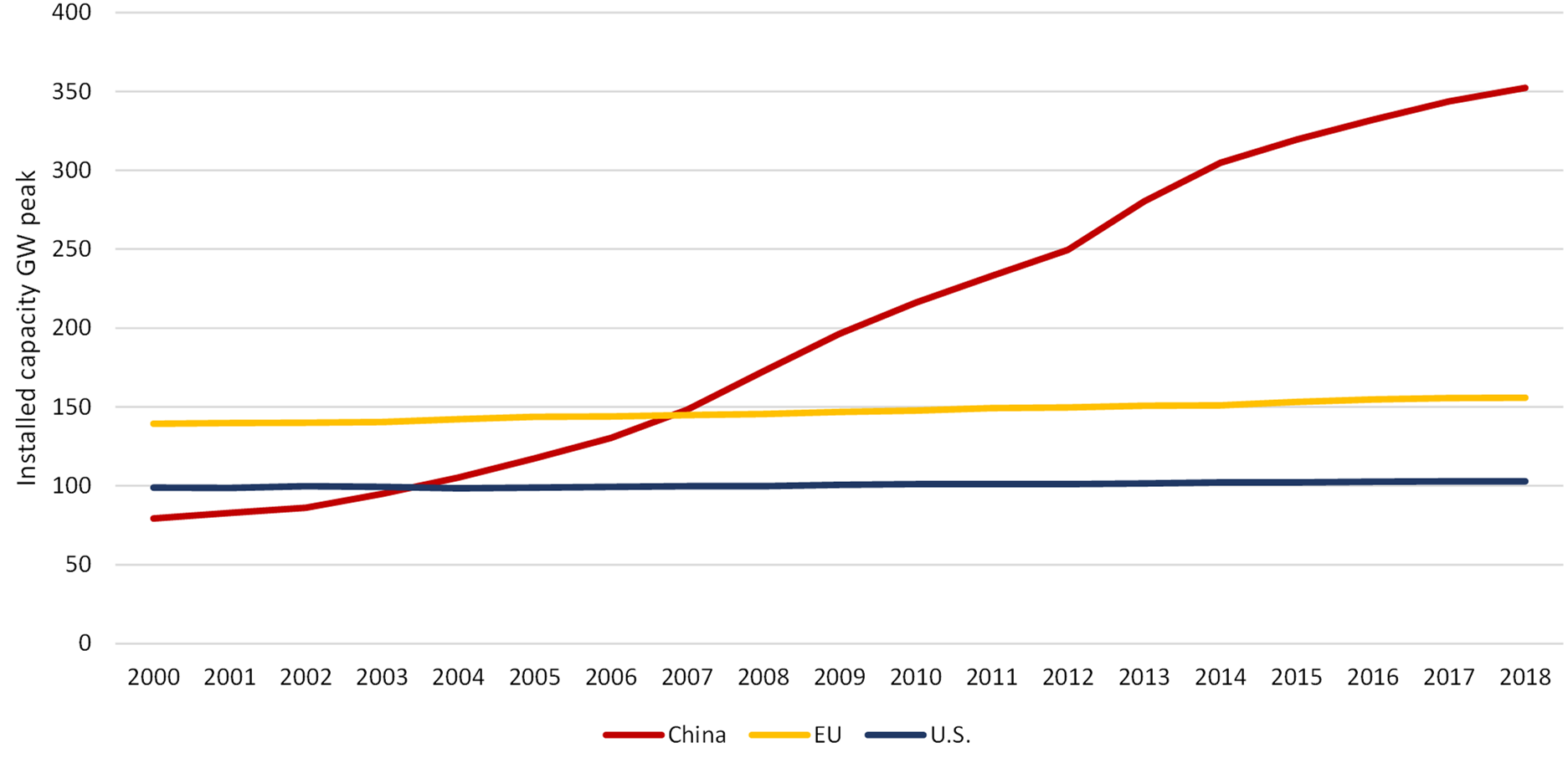

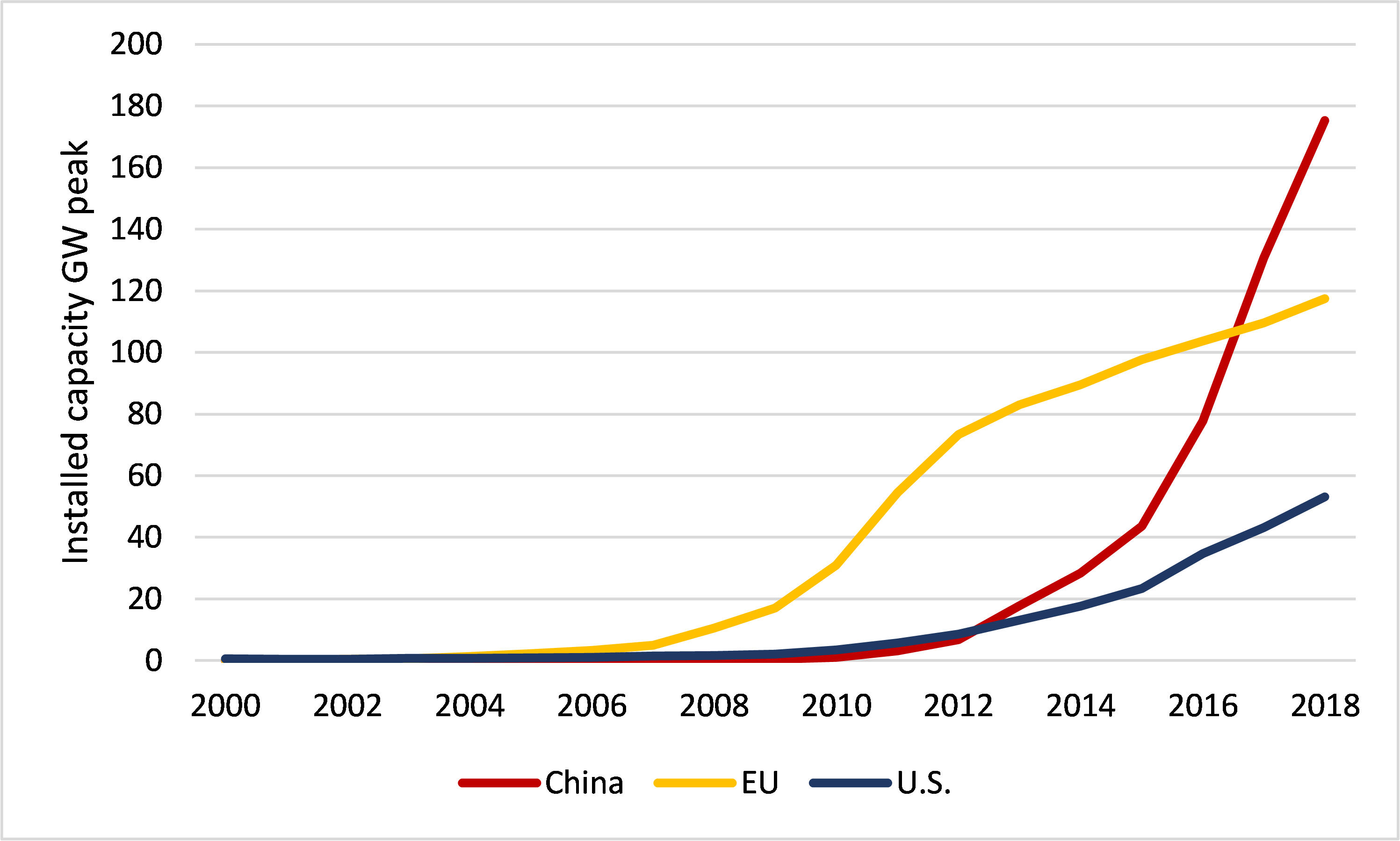

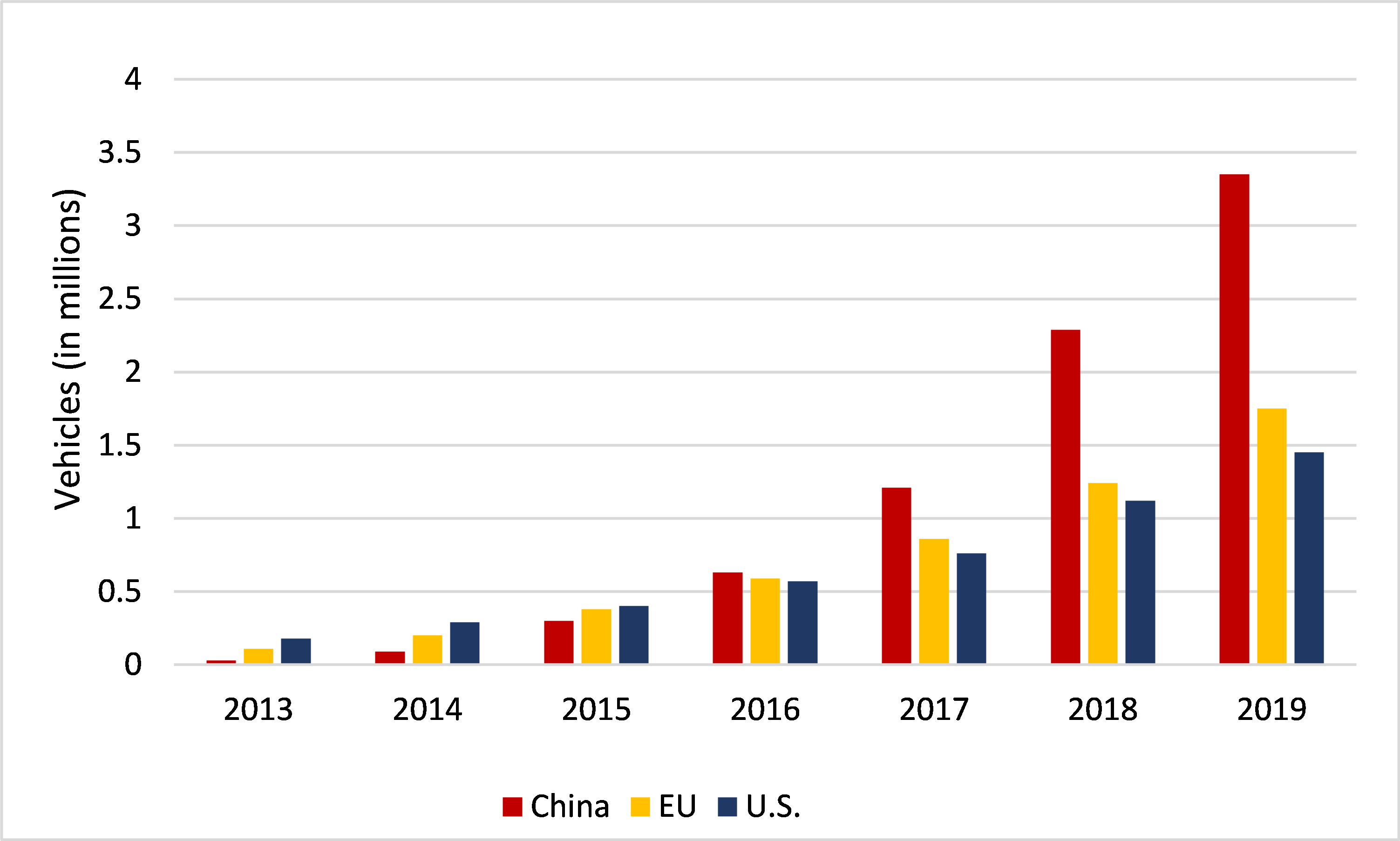

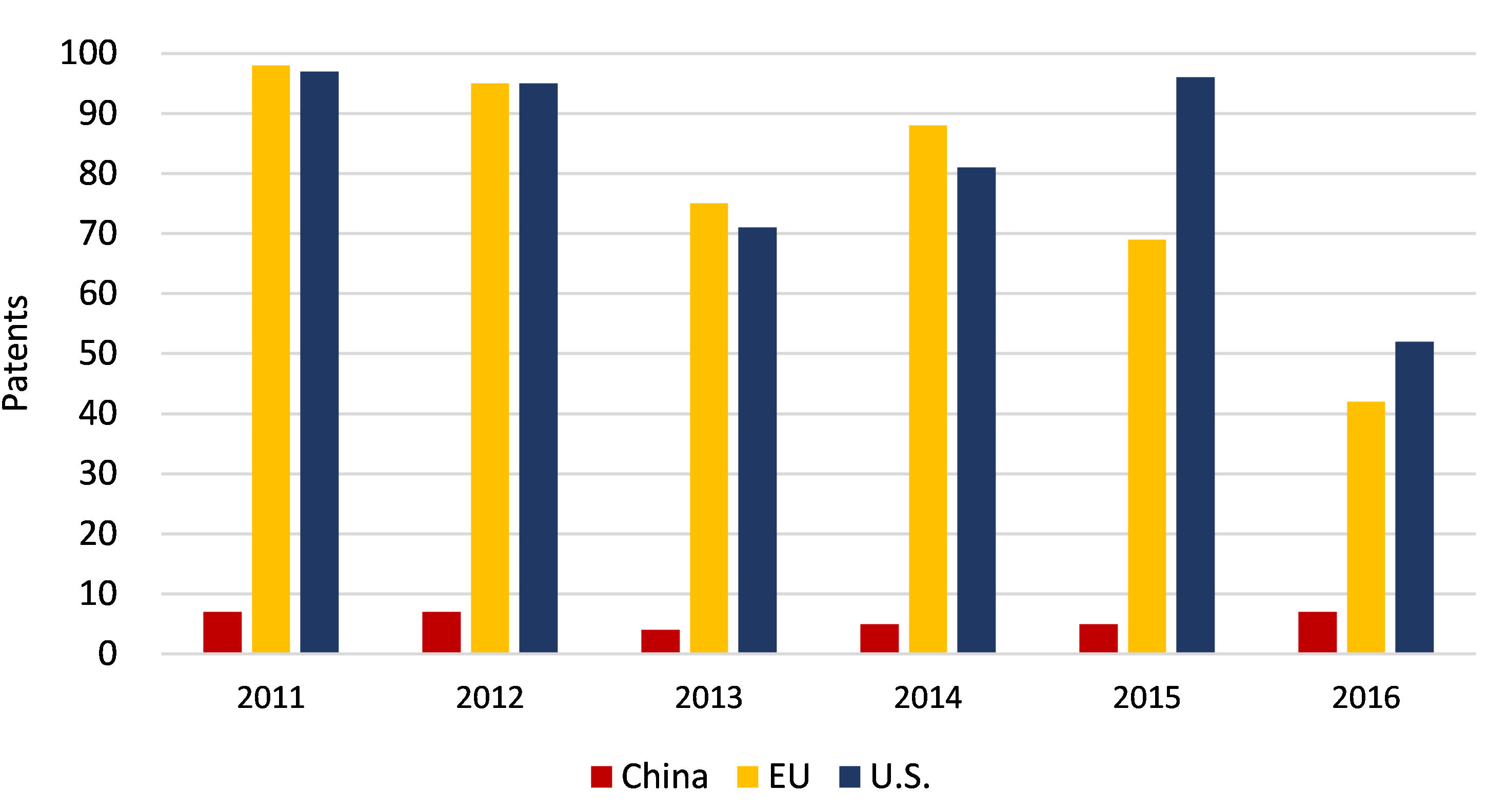

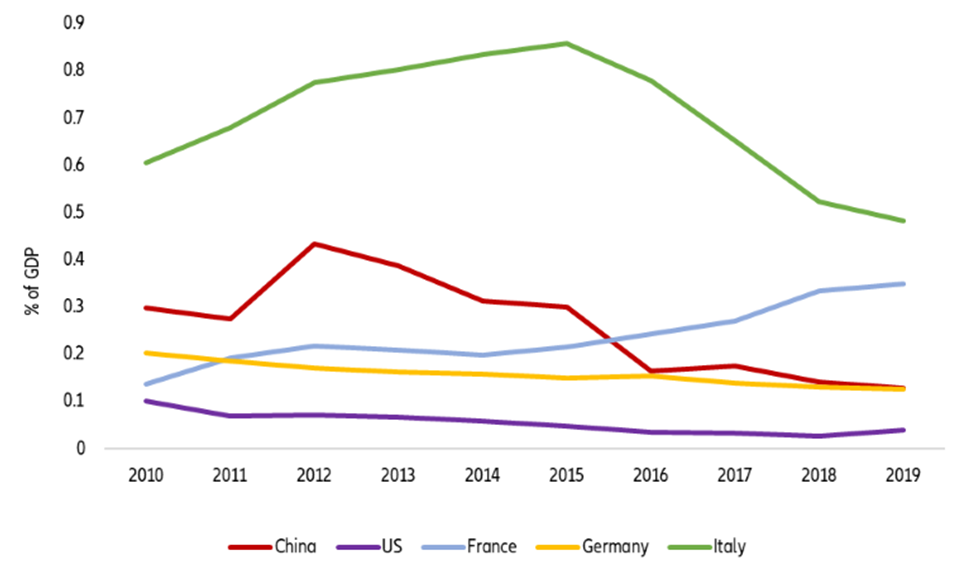

How do the three countries compare in climate policies? China is already leading the pack in renewable energy and electric vehicles, but is lacking in carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology and subsidies for fossil fuels. China’s rise in renewable energy is breath-taking: it has recorded an over 800% increase in installed capacity for renewable energy since 2000, while the EU and the U.S. saw “only” 230% and 160%, respectively. As a result, installed capacity in the U.S. is now around one third of that in China, and the EU stands at two thirds. Back in 2000, all three economies were more or less on the same level. In addition, China’s Electric Vehicles stock is higher than that of the U.S. and the EU combined. The U.S., however, is still leading CCS technologies and has the lowest subsidies for fossil fuel among the three economies.

The race for being a climate superpower is open – but it is too early to choose a winner. Our comparative analysis makes it clear that all three economies have to accelerate their climate efforts, materially and quickly. But all face different hurdles. China’s commitment towards climate neutrality lacks visibility. The EU’s Recovery Fund might be stuck or watered down in its Kafkaesque bureaucracy. And the U.S. has to overcome its highly divisive elections. Even after Covid-19, climate policy remains a race full of hurdles. But unlike the wrangle for technological and geopolitical hegemony, this might produce the right winner: the global climate.

U.S., EU, China: not on track to 1.5°C

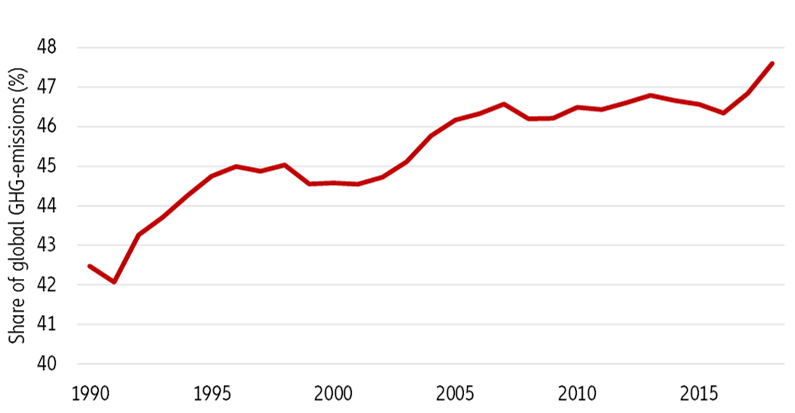

The Paris Climate Agreement, adopted in 2015 and approved in 2016, set a long-term goal to limit an increase in the global average temperature to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, compared to the previous less ambitious goal of 2°C. China, the EU (defined to include UK) and the U.S. accounted for almost half of all global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2018, with a clear upward trend (see Figure 1). So the performance of these three economies will be decisive for reaching the Paris Climate Agreement goals.

Figure 1: Combined greenhouse gas emissions of China, the U.S. and the EU