In focus – Commercial real estate concerns for US banks

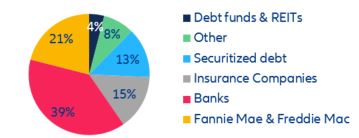

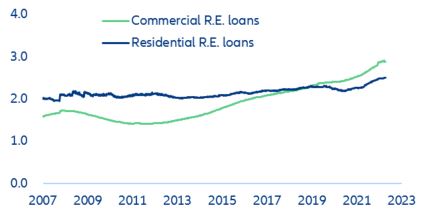

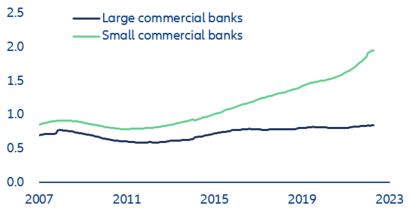

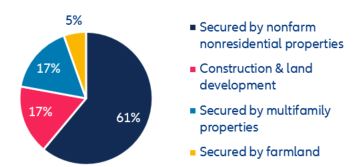

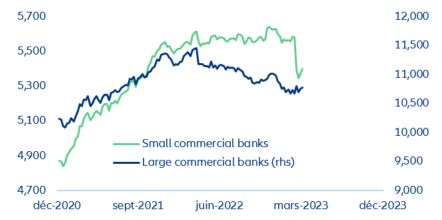

- Some US banks remain under pressure, especially those with large exposure to commercial real estate (CRE). The office sector in particular has come under market stress. While CRE credit risk has remained stable so far, declining market valuations have resulted in more stringent lending standards, especially for smaller US banks, which hold a disproportionately large share of CRE loans. In parallel, credit demand has noticeably weakened.

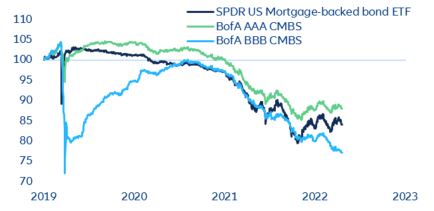

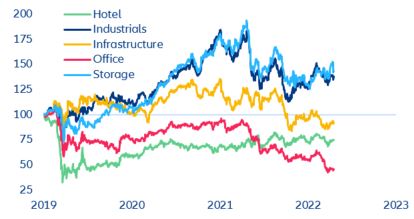

- Potential risks from CRE extend beyond the banking sector. CRE-related fixed-income public markets have already corrected by about 20-30%, with increasing differentiation depending on credit quality. Similarly, CRE-related equities have declined in value and Real Estate Investment Trusts, despite being more liquid, have sold off after redemption pressures from investors.

- The impact of CRE losses call for increased scrutiny. Rising impairments of CRE exposures weighing on solvency would further constrain lending activity and complicate the Federal Reserve’s job in keeping a restrictive monetary stance; such an adverse scenario is also likely to further test the resolve of policymakers to shore up investor confidence if more banks book rising unrealized losses from fixed-income holdings.