EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

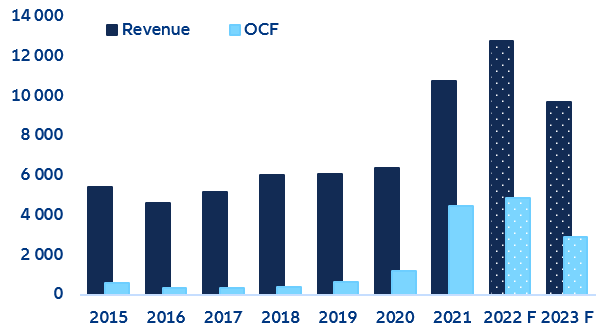

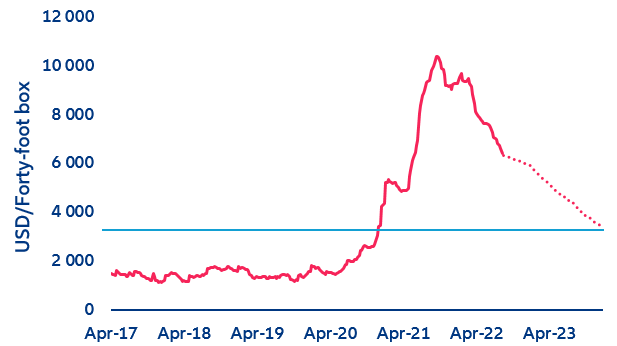

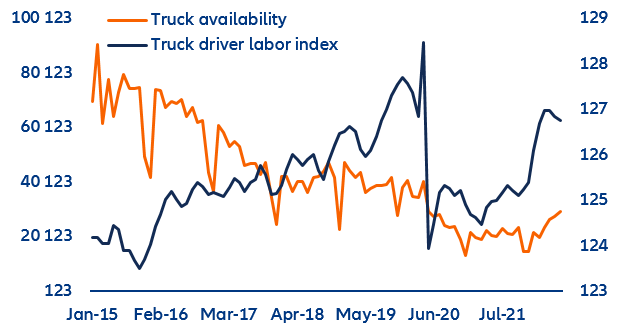

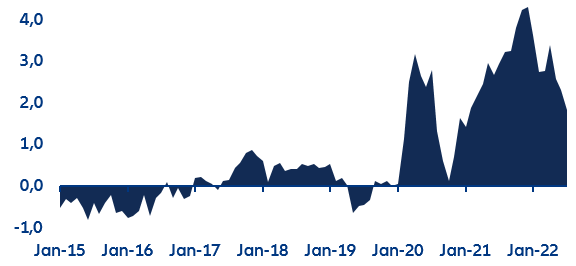

- 2022 will be a record year for container shipping companies. We expect the sector’s revenue to jump by +19% y/y and its operating cash flow to grow by +8% y/y. While freight rates have fallen -32% year-to-date, they are still well above the pre-pandemic average (USD6,400/forty-ft box vs. USD1,450/forty-foot box). Freight rates are likely to remain elevated in 2023 (USD 4,550/forty-foot box), given the delayed delivery of new vessels, new regulations on CO2 emissions, continued truck-driver shortages and higher prices for fuel, containers and vessels.

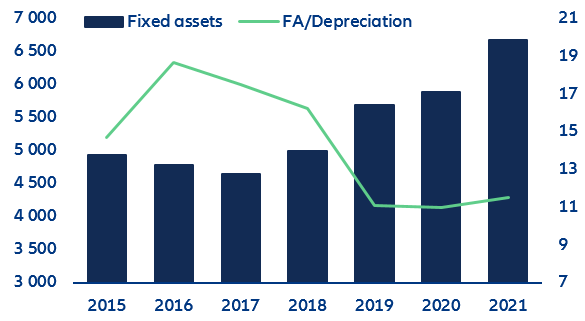

- Higher-than-expected cash generation has helped liners comply with new ESG standards (with investments growing by +61% y/y in 2021). In addition, gross debt fell -5% y/y in 2021 and we expect companies to deleverage further in 2022 and 2023 (-16% and -11% y/y, respectively), which will be crucial in a context of increasing interest rates.

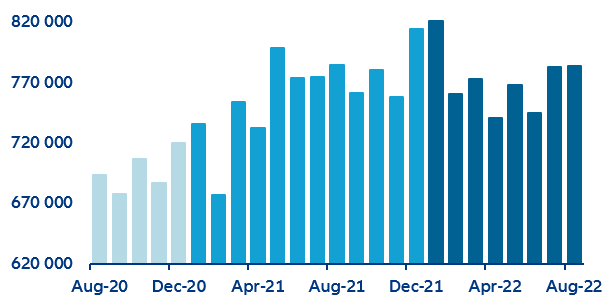

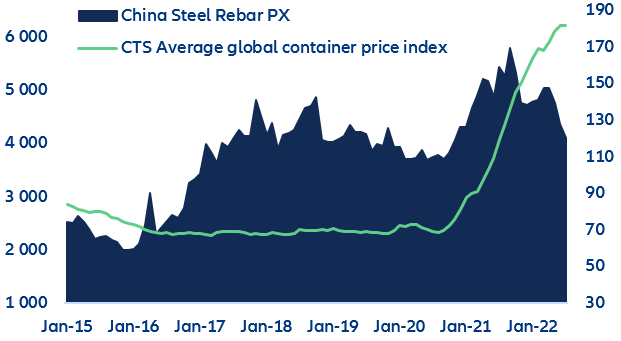

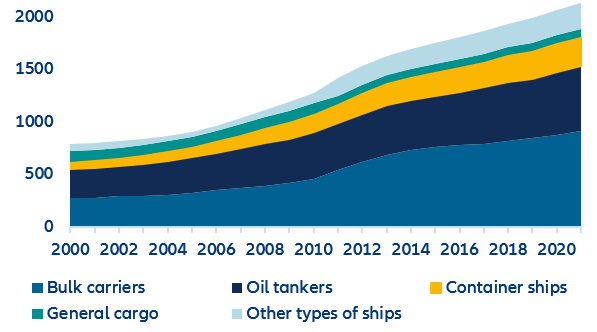

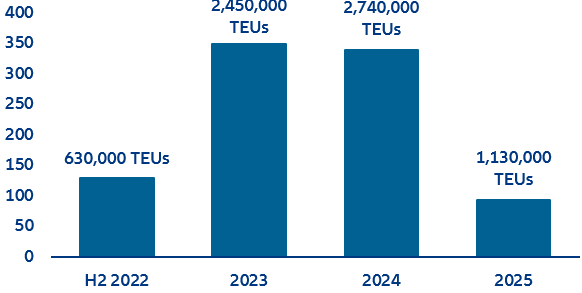

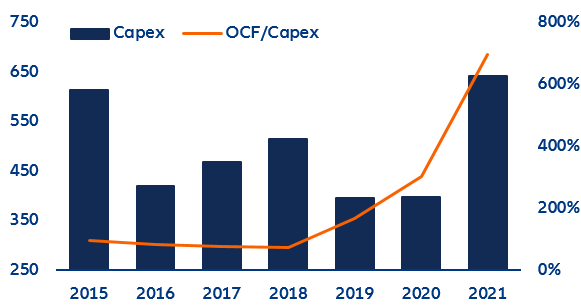

- However, despite increased capital expenditures (capex), shipping capacity will not increase as much as expected nor as fast as desired. The recent investment efforts, although huge, have not been in line with the sector’s capability (cash from operations grew by +274% in 2021 on average) and most of the capex increase is explained by the fact that the price of new vessels doubled last year, not because of larger new orders. In addition, while 35% of orders should be delivered in 2023 and 39% in 2024, these ships are likely to modernize the fleet instead of fully expanding it as IMO 2023 regulations force companies to retire older ships.

Freight rates will not return to pre-pandemic levels in the short-term.

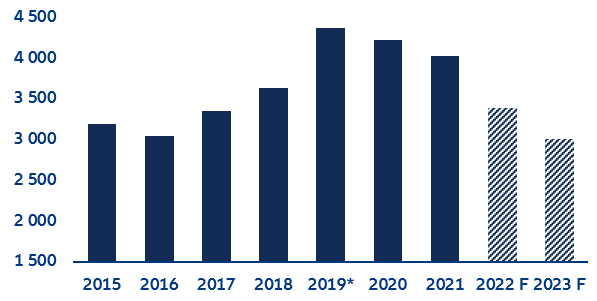

After almost doubling its revenues in 2021, the global container shipping sector is heading for another record year as freight rates show no sign of returning to pre-pandemic levels in the short term. Considering a sample of 30 global shipping companies, the sector’s average revenue growth rate was +70% y/y in 2021, totaling around USD11bn per company. The average net profit came to USD3.5bn, particularly high for a sector that barely reached breakeven during the past five years.

Figure 1: Average revenue and operating cash flow (OCF) of the global industry (USD mn)