EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The automotive industry has been the number one casualty of the global semiconductor crunch: We estimate that it led to a shortfall of about 18mn vehicles around the world.

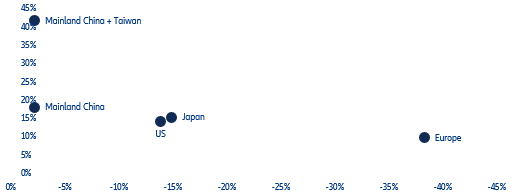

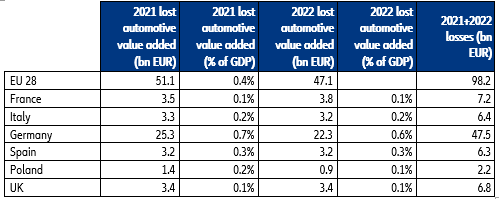

- Europe’s automotive sector has been hit the hardest, and its weak semiconductor sector did not help. We estimate that the semiconductor crunch will cost Europe about EUR100bn over 2021 and 2022.

- As vehicles will only get more ‘semi-intensive’, the automotive sector will need policy support to avoid more losses in the future. However, support should focus on segments where Europe is both a large manufacturing and final market, i.e. automotive and not consumer electronics.

The global automotive chip shortage has created a shortfall of 18mn vehicles.

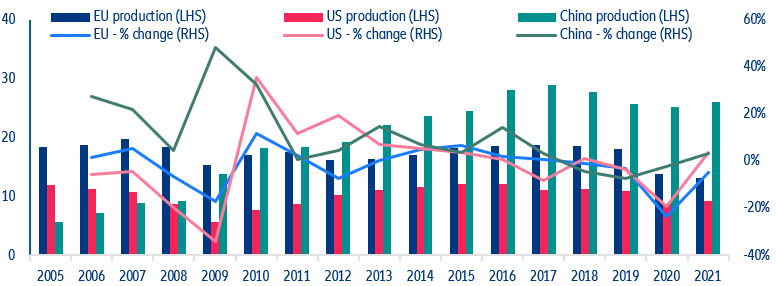

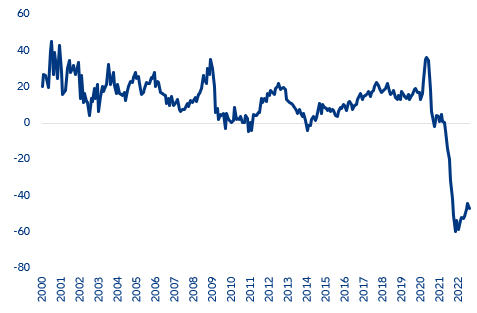

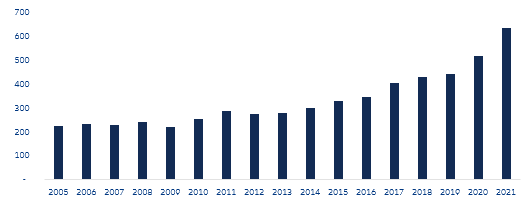

The automotive industry has been the number one casualty of the global semiconductor crunch. Bracing for tough times at the beginning of the pandemic, carmakers and automotive suppliers responded with deep cuts in semiconductor inventories and orders. As demand for cars recovered faster than expected in the second half of 2020, the industry discovered that chip manufacturers had reallocated production capacities to end-markets with booming demand, such as computers and data centers, leaving little capacity for the automotive sector. Nearly two years on from the first signals of a semiconductor shortage, car production remains far below its 2019 level, with a cumulated production shortfall of over 18mn vehicles globally. The situation has been comparatively worse in Europe where, unlike in China or North America, vehicle production fell to an unprecedented low of 13mn vehicles in 2021 (Figure 1). After signs of improvement in late 2021 and Q1 2022, the production recovery was again held back by additional supply-chain tensions caused by lockdowns in the wider Shanghai region and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Figure 1: Vehicle production (mn units, % change)