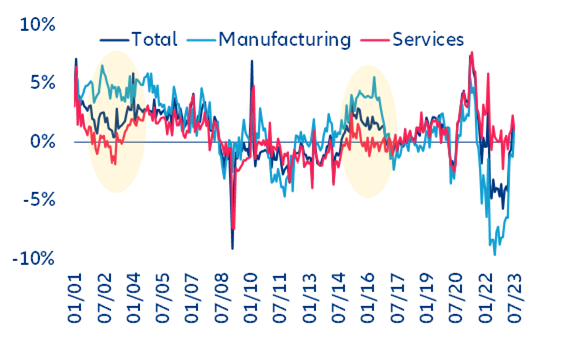

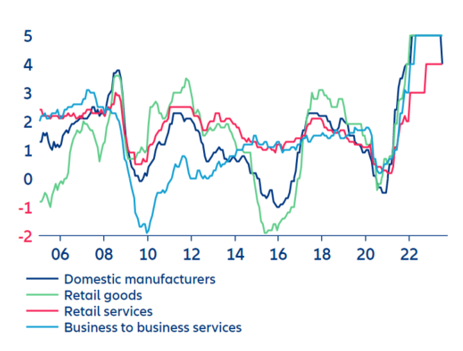

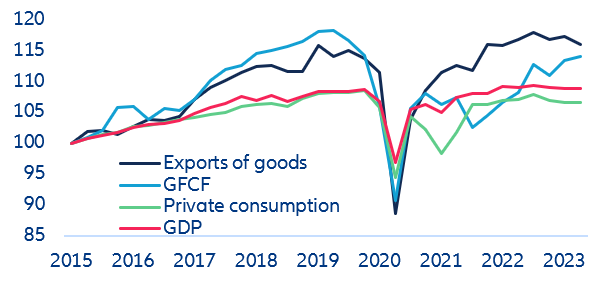

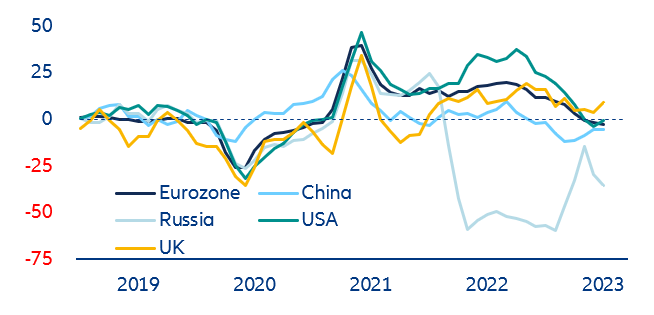

Finally, an inventory correction will cause a further fall in manufacturing output. After a more-than-usual increase in inventories when pandemic-related shortages ceased, retailers are now paring back their stocks of inputs and finished goods amid flagging demand. With its huge export-oriented manufacturing sector, Germany will again be hit harder than most other European economies.

Will the government’s latest rescue plan save the day? Some of the cyclical issues are intertwined with more structural headwinds that hold Germany back. These include pervasive labor shortages, excessive energy costs partly caused by misguided energy policies in the past, high regulatory and tax burdens, slow digitization and policy uncertainty. Compared to the troubles of 1995-2004, however, Germany today enjoys record employment, high demand for labor and a rather comfortable fiscal position. That makes it much easier to adjust to shocks. Nevertheless, the current downturn may serve as a wake-up call. While growth-enhancing reforms were blocked until 2002 by the then center-left coalition, the current government shows less resistance and recently put forward a rescue plan. The 10-point economic plan tries to tackle the headwinds and to create stimulus for the economy. The Growth and Opportunity Act makes up the core and complements existing measures to provide tax support for companies and climate-friendly investments. These include an investment premium, tax-loss deduction, improved depreciation terms, a temporary reintroduction of declining-balance depreciation options for movable assets and residential buildings and strengthening tax incentives for research and development. They are expected to result in a tax cut of EUR7bn per year up to 2028. The expanded depreciation options provide a stimulus of EUR500mn specifically for housing construction.

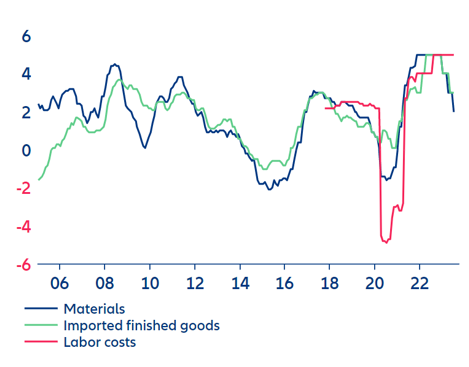

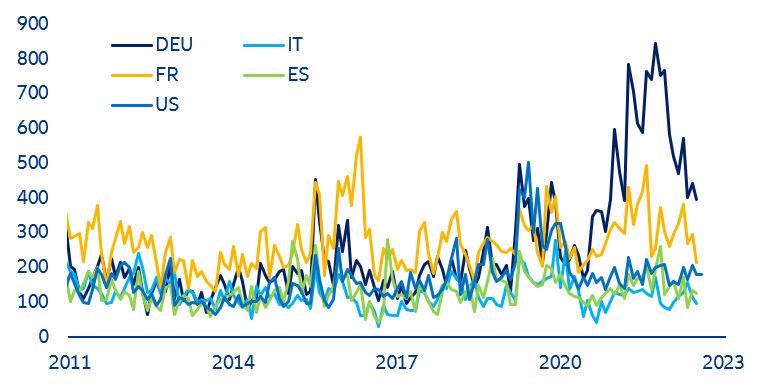

While the plan is a step in the right direction, and will give growth a small boost, it is too small to restructure a EUR4trn economy. Even before announcing the current plan, the government attempted to create some stimulus for investments through industrial policy. But the problem is not a lack of funds, it is the nature of the administration itself. Germany currently has to pay the price of its partially misguided past energy- and managing-rather-than reforming policy choices. As net-zero targets are achieved and energy prices remain higher for longer, a loss of some of energy-intensive industries is inevitable. This will hurt as the chemical and metal industries are among the most research-intensive ones and produce more innovations on average than other industries. As they generate about 20% of industrial value add in Germany and employ about 16% of the industrial workforce, this will have a significant impact on prosperity.

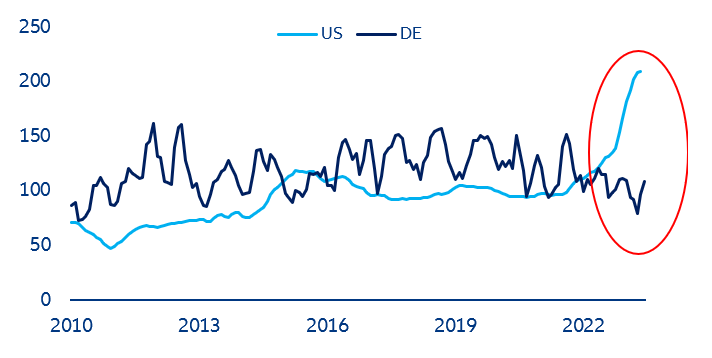

Germany’s transformation process is already in full swing. Companies have begun to leave Germany for locations with cheaper energy. Nevertheless, the German government has proposed an 80% electricity price subsidy for heavy industry (Industriestrompreis), which carries a EUR30bn price tag – though this is not yet decided. It has also drafted subsidy plans for clean production in heavy industry worth around EUR20bn and EUR20bn of subsidies have already been earmarked for chip production plants, of which EUR10bn alone will go to Intel. Yet, it remains to be seen whether this will be enough to drive private investments in Germany, the way investments associated with the Inflation Reduction Act contrary have pushed up new plant investments in the US (Figure 13).