Executive Summary

The US equity market rally since 23 March has surprised and wrong-footed more than one professional investor. We see four valid explanations for the current decoupling between the U.S. equity market and economic fundamentals.

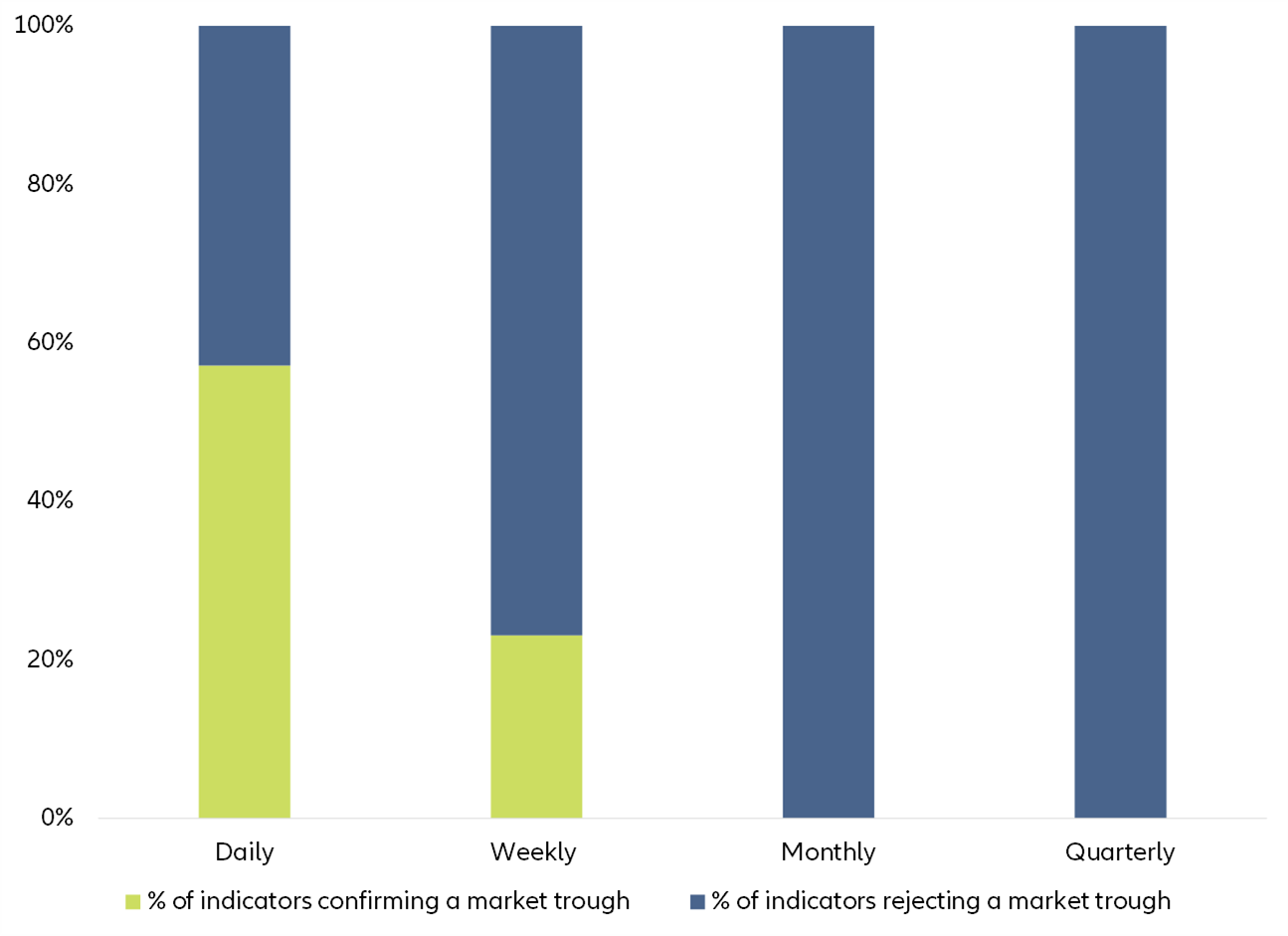

- Diverging expectations in the shape of economic recovery and economists’ consensus.

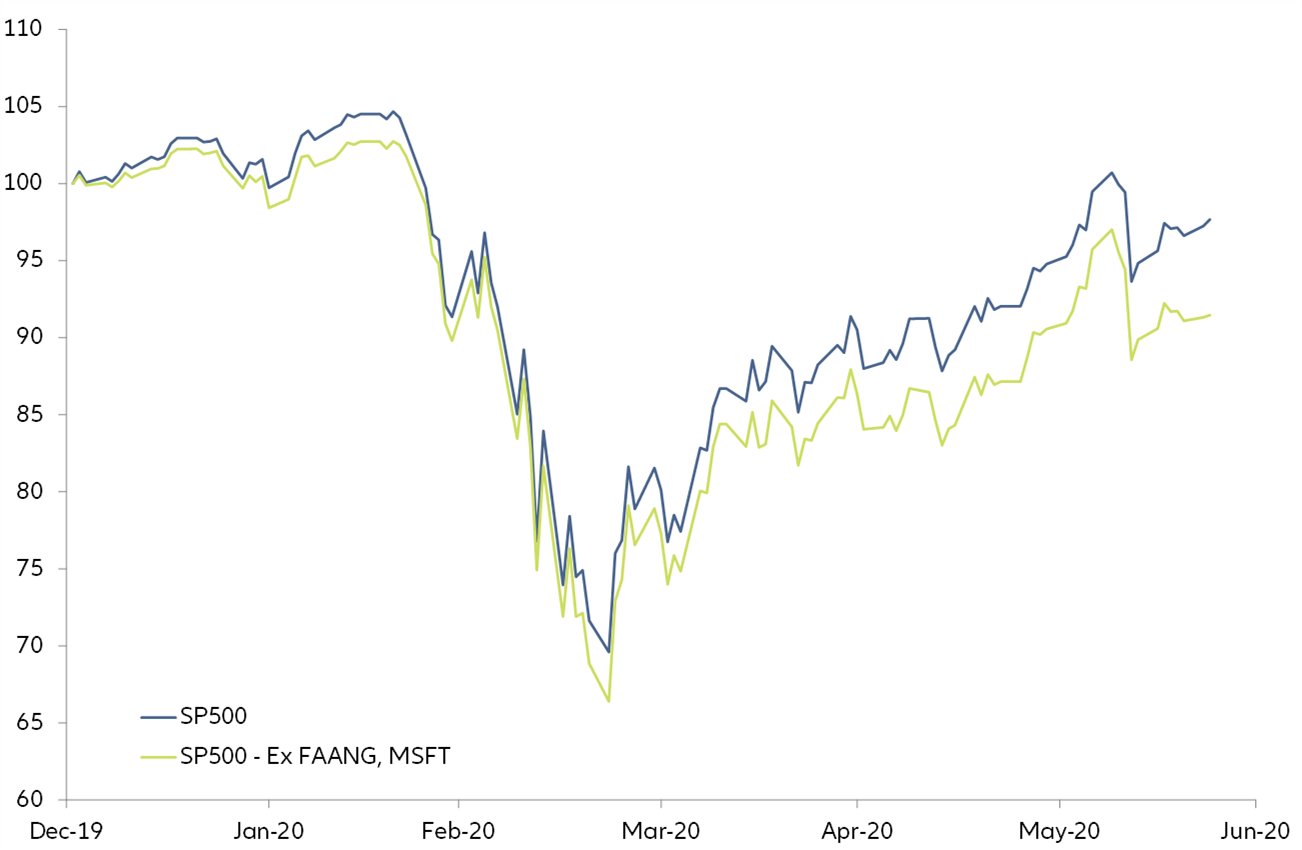

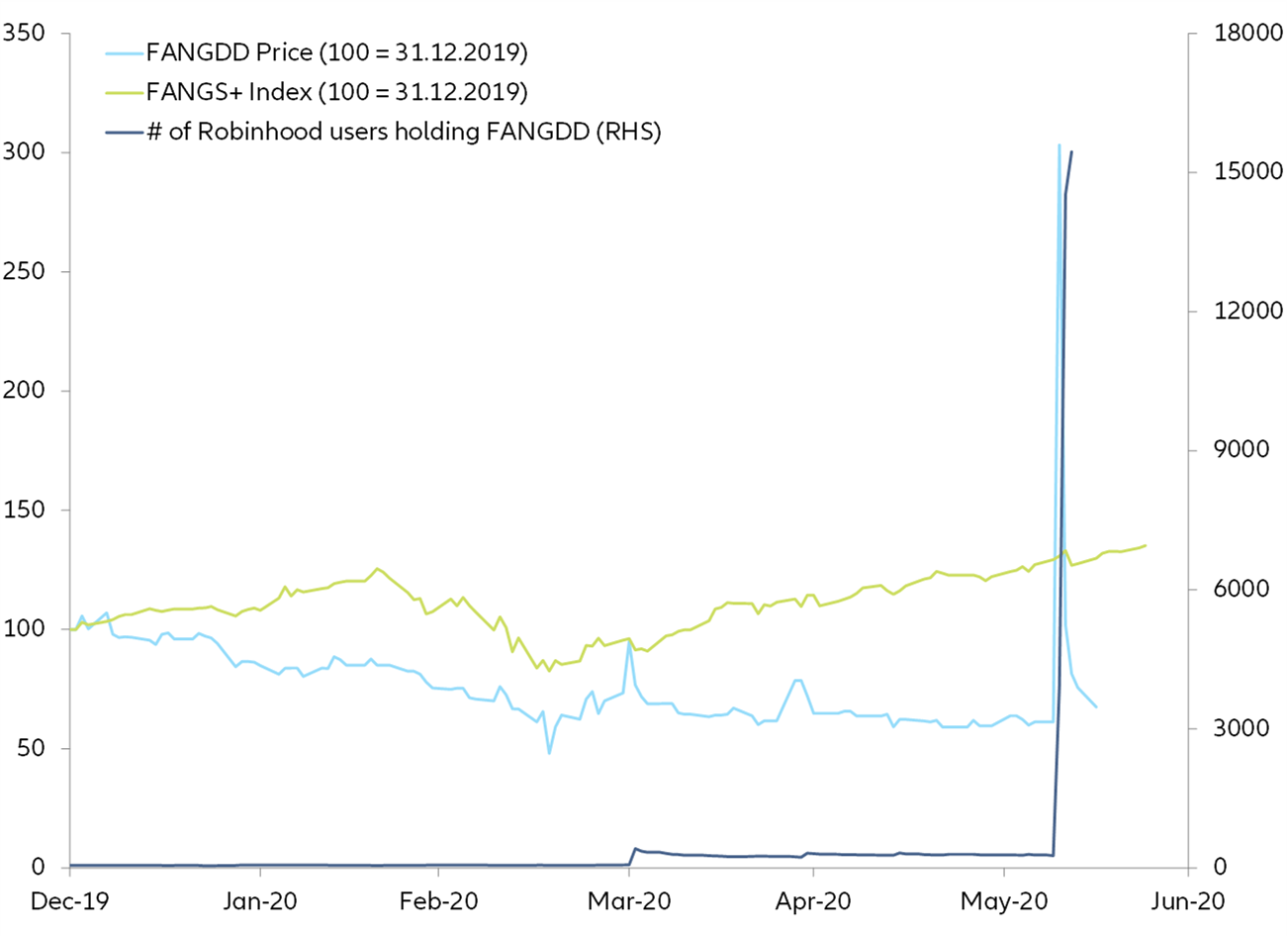

- Diverging earnings expectations among sectors (technology) or stocks (FAANG).

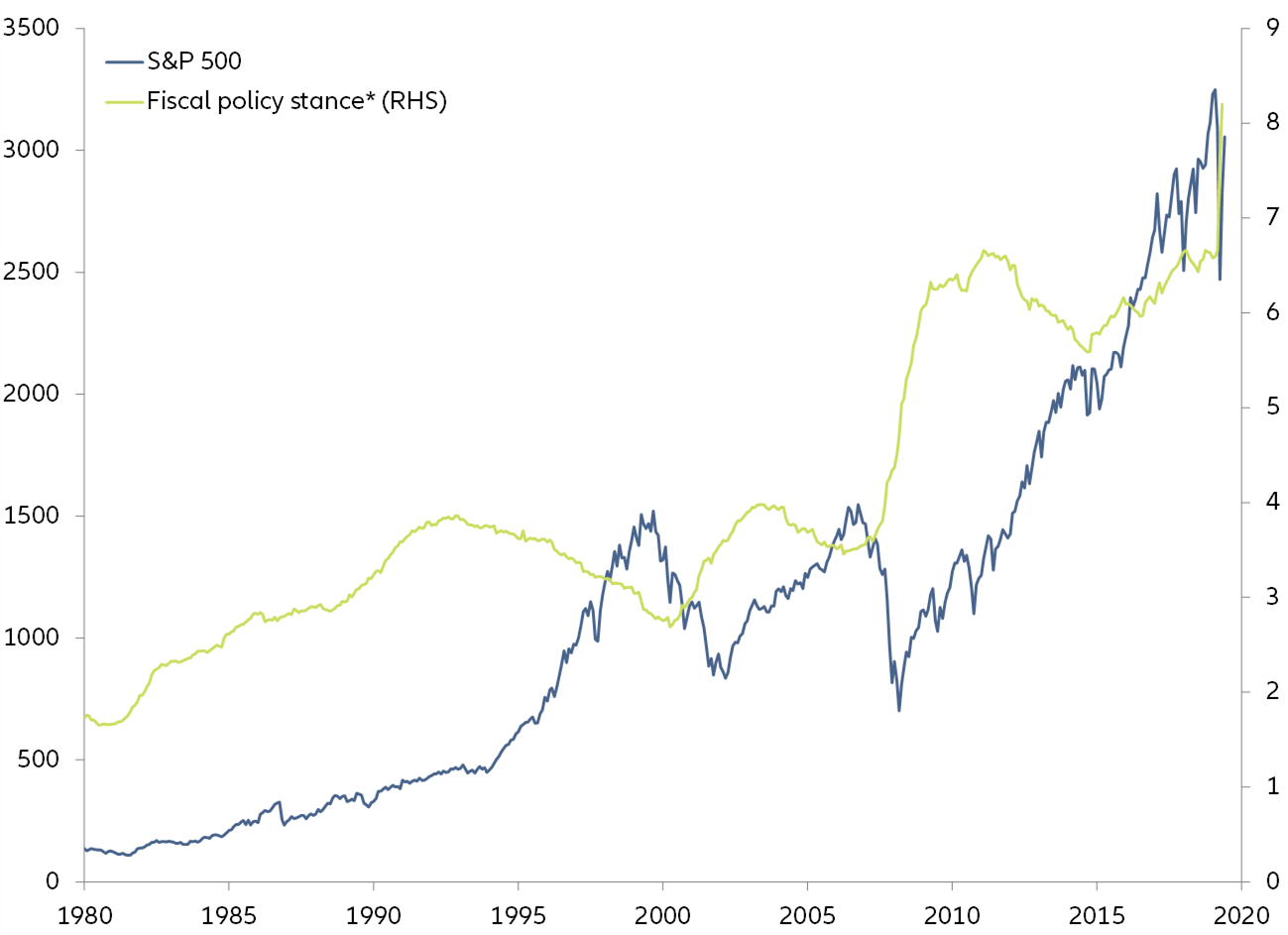

- “Pavlovian markets” only reacting to announcements of expansionary monetary and/or fiscal policy.

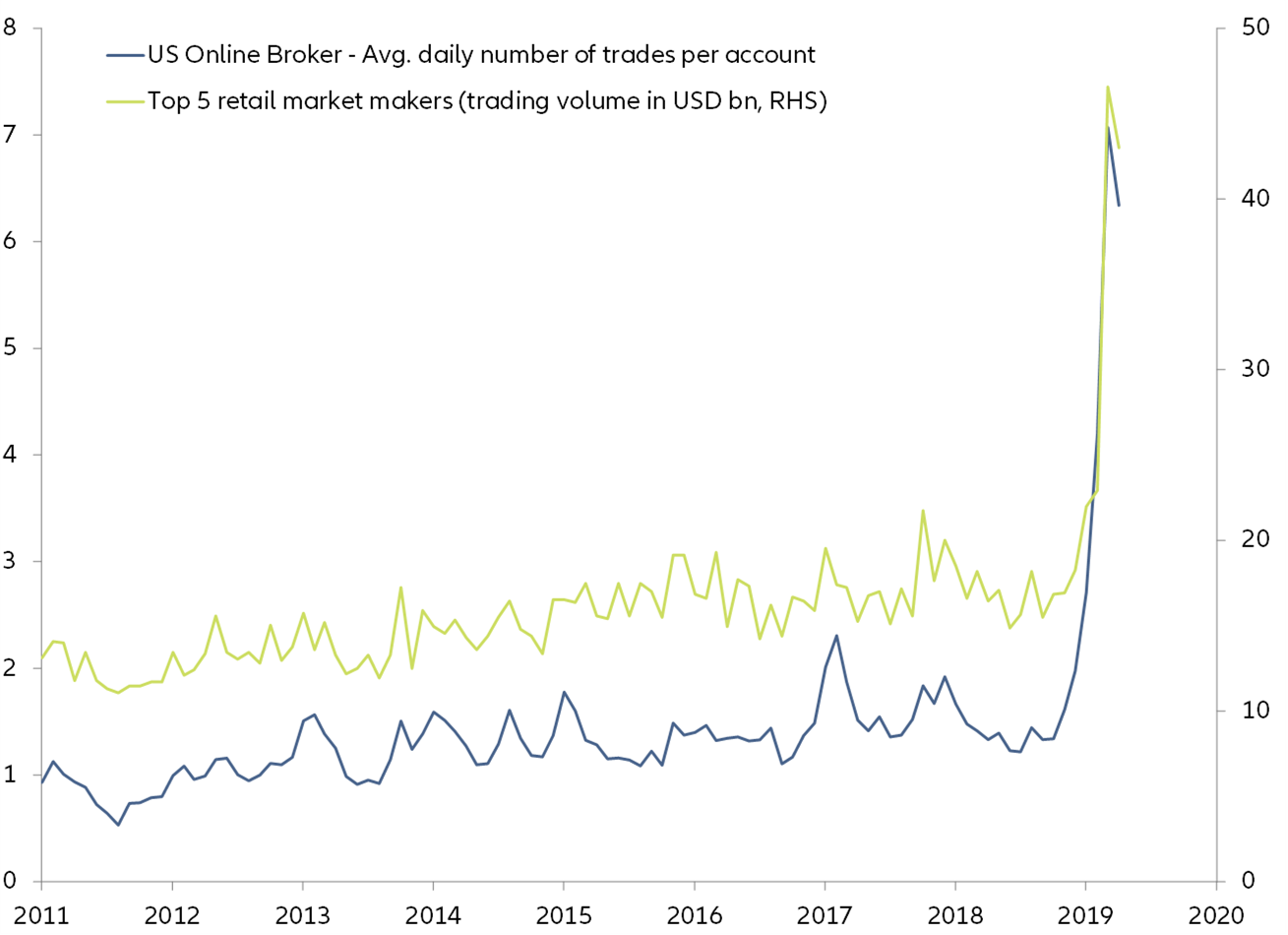

- A technical rally, the momentum of which comes from the “new retailers” and is reinforced by systematic investment strategies.

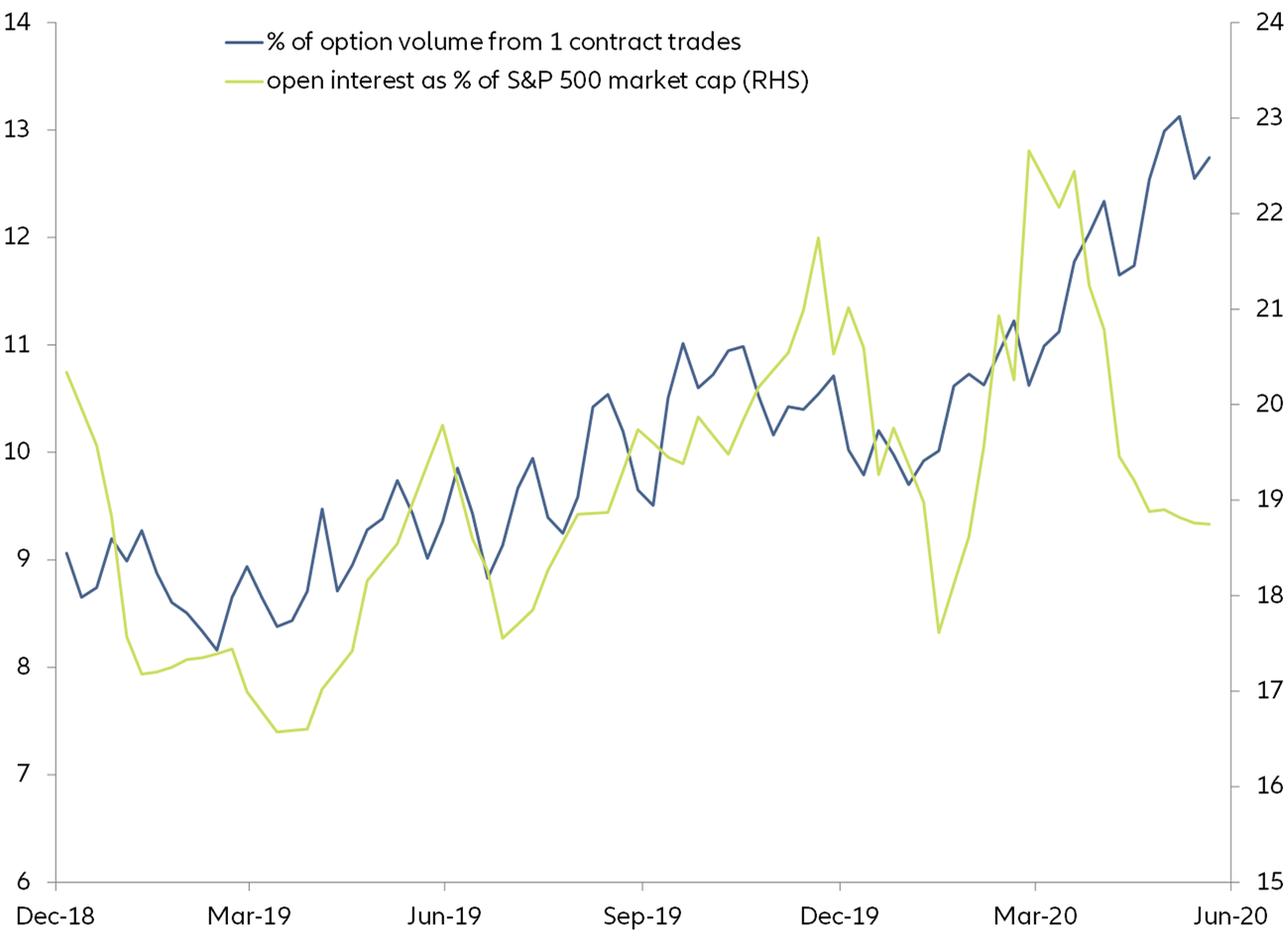

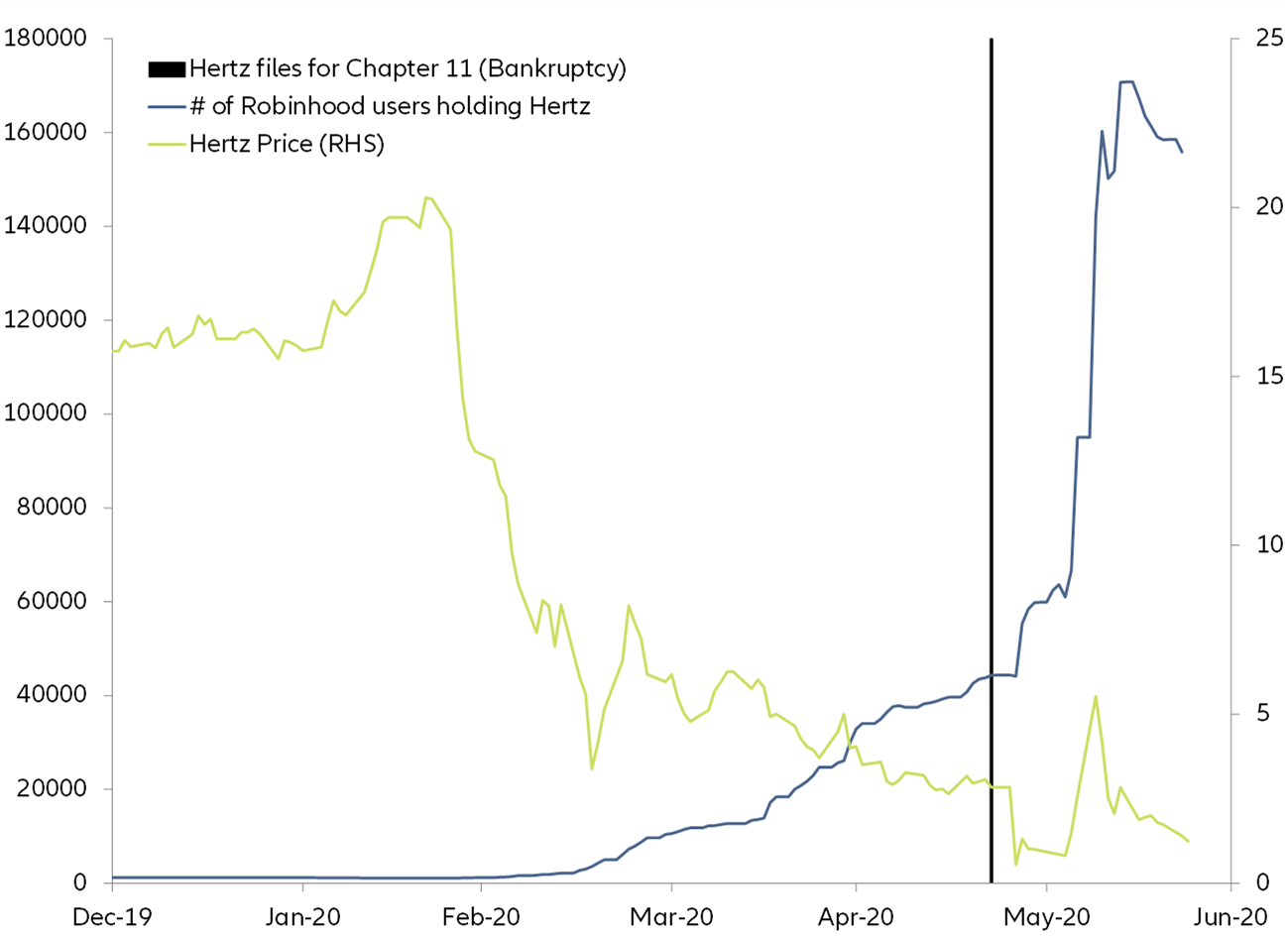

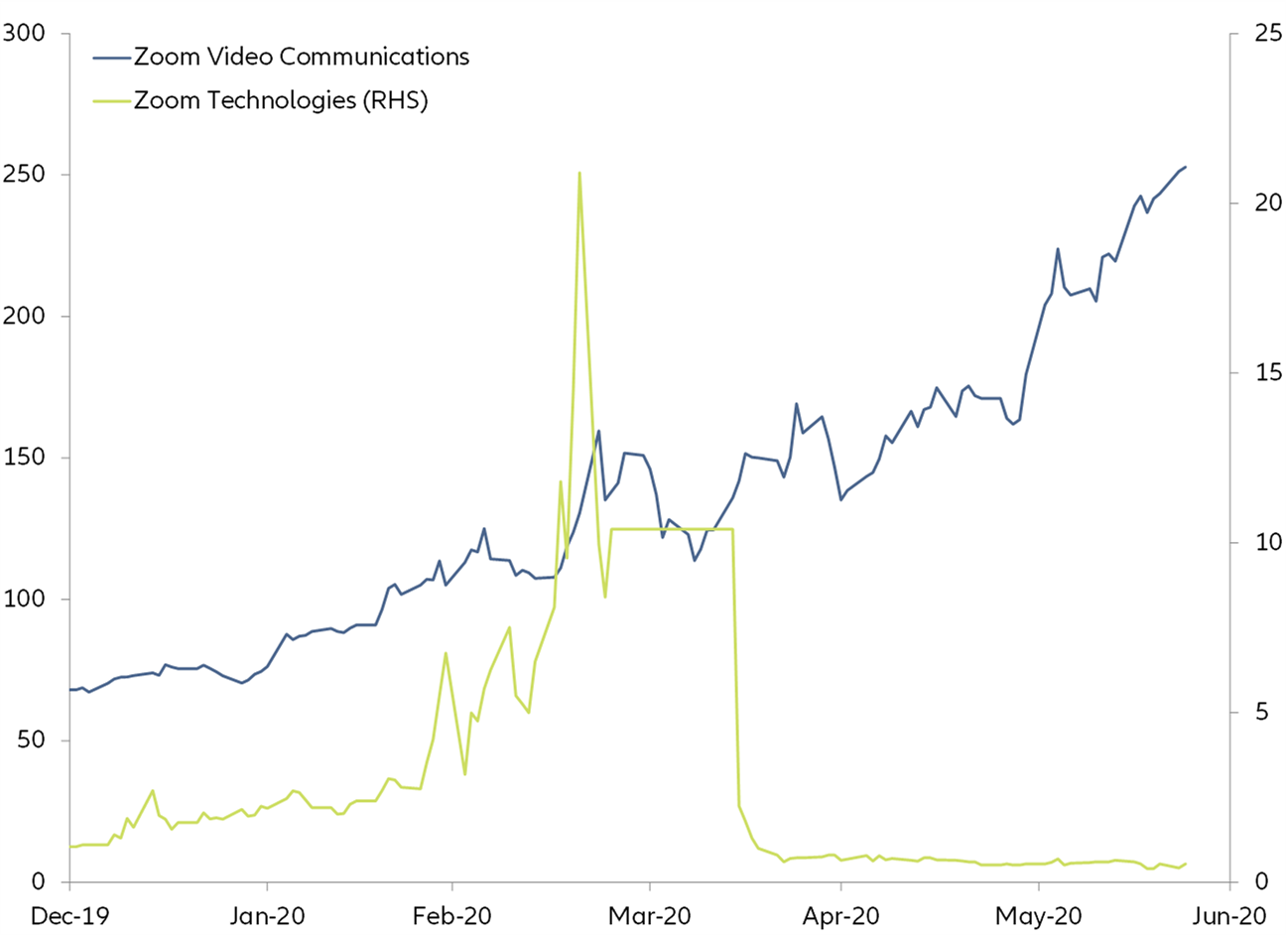

We consider the last two arguments are the most convincing. New retail investors’ expectations are formed in different peer groups than those of professional or experienced retail investors: it is not financial media that prevails but social (lifestyle networks). The investment behavior of the "new retailers" shows an alarming extent of risk-taking (consciously or by lack of financial literacy) not least by the extensive use of derivatives. In certain market segments, "new retailers" have already become very significant (distressed equity, penny stocks). The current U.S. equity market conditions seem fragile to us due to the decoupling from fundamentals and the highly speculative investment rationale, as well as the regulatory and operational risks.

Four explanations for the disconnect between the equity market and the real economy

The U.S. equity market rally starting 23 March has surprised and wrong-footed more than one professional investor. While the real economy is heading for the worst recession since WWII, equity markets seem to have already left behind this wall of worries. How can this puzzle be solved?

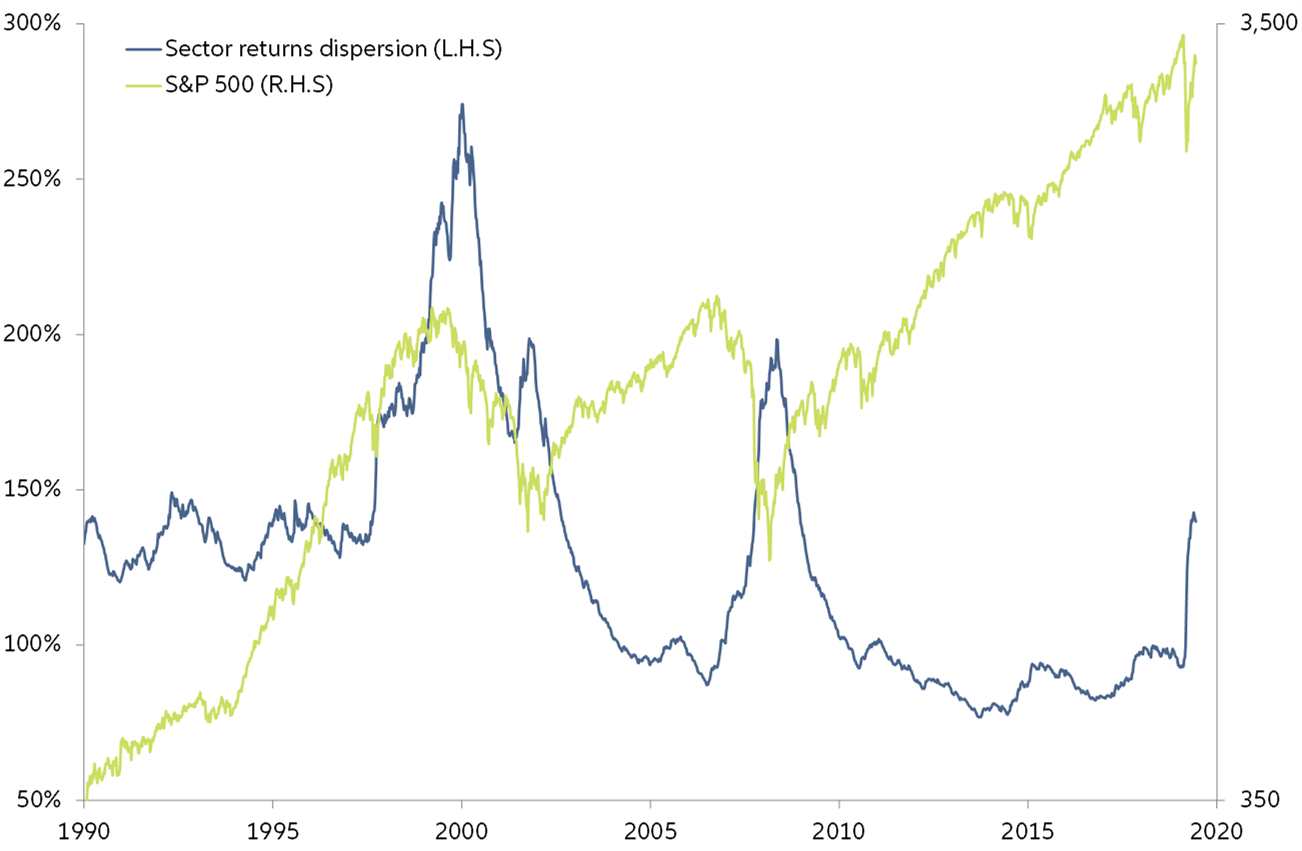

We consider four explanations as being potentially valid to explain the decoupling between the real economy and equity market performance. The first three are based on expectations theory, which means that the current state of the market embodies aggregate rational expectations of market participants for the real economy, monetary policy or single stocks. The difference between the three explanations lies in the interpretation of which expectation element is dominant in the current market.

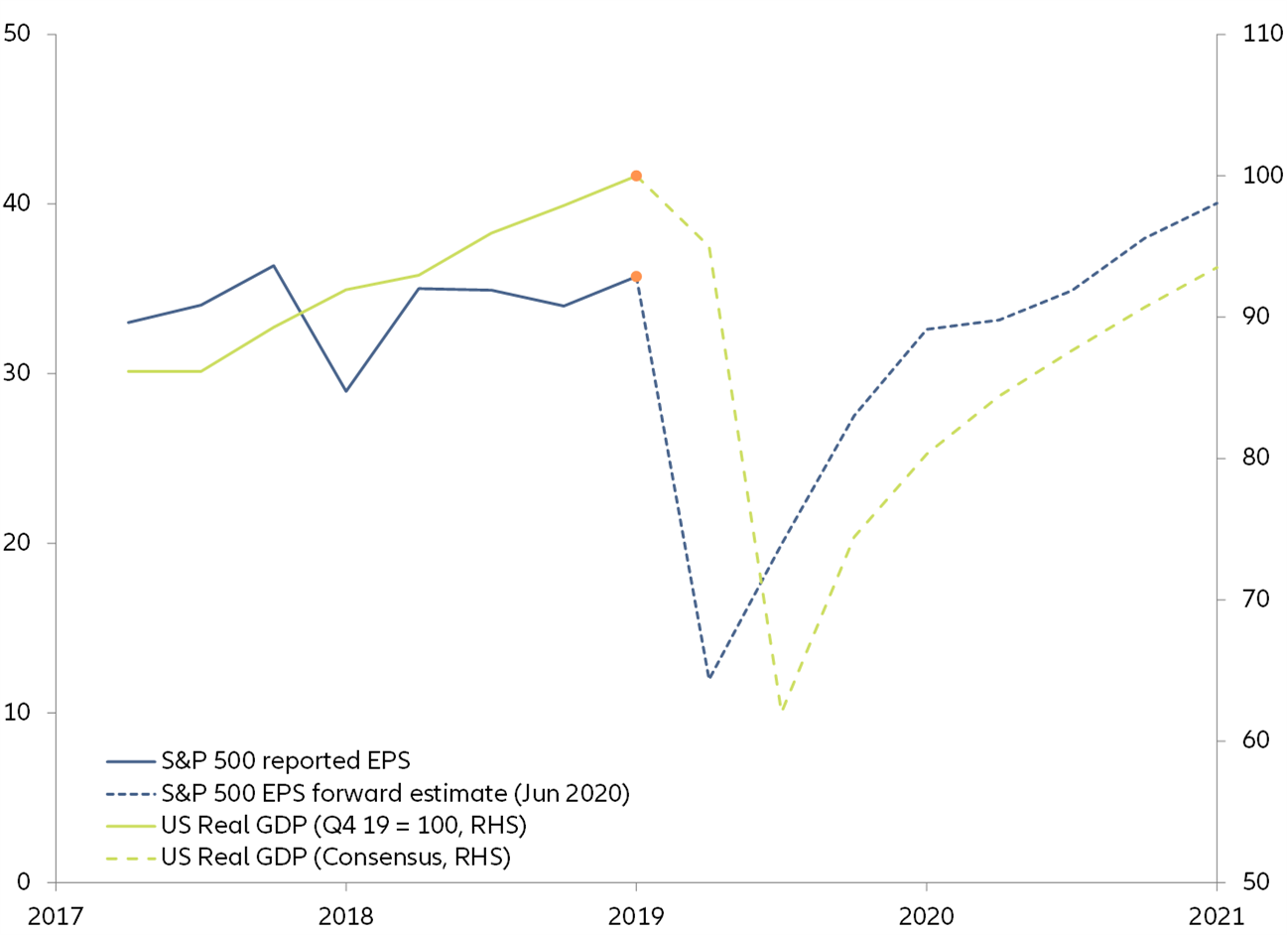

V-shape vs consensus. The first explanation is based on diverging expectations between equity market investors and policymakers, bond markets and international organizations as to the shape of the U.S. economic recovery. As of today, the equity market is pricing in a rapid recovery of the entire U.S. economy, with the S&P 500 expected to return to pre-crisis EPS (Earnings per Share) in H1 2021 (Figure 1). Meanwhile, international organizations (IMF, OECD) and the economists’ consensus expect the economic recovery to be much slower, with pre-crisis levels only being reached one year later in H1 2022. This means that equity markets don’t see any long-term scars on the U.S. economy from the Covid-19 crisis or that they expect the large listed U.S. companies to decouple from the rest of the U.S. economy strongly, consequently driving U.S. equity indices higher.

Figure 1: EPS vs. growth consensus, are we on the same page?