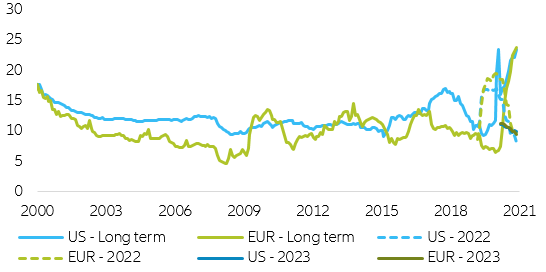

Figure 1: US short vs long end of the sovereign curve (in %)

Figure 1: US short vs long end of the sovereign curve (in %)

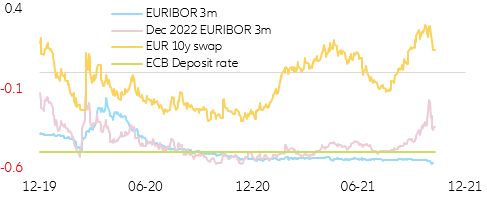

Figure 3: US long-term sovereign vs equity implied volatility (in %)

Besides the rapid demographic change, most markets have one further argument in common for striving for demography-proof i.e. sustainable and adequate pension systems: Due to their fiscal support measures to cushion the impact of the Covid-19 crisis, general government gross debt has increased and thus their future financial leeway to subsidize pension systems has shrunk. However, there are marked differences with respect to the degree of indebtedness: while the gross budget deficit of Japan is expected to reach 266%, that of Hong Kong will probably remain below 1% (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: The Covid-19 crisis has diminished governments’ financial leeway

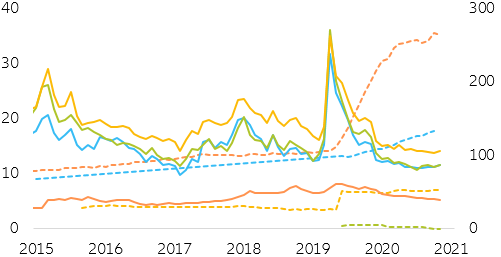

Sources: ICE BofA, S&P, Barclays, Refinitiv, Allianz Research

*investable universe proxied using IG BofA indices;

**full line indicates spreads and dotted line central banks’ ownership

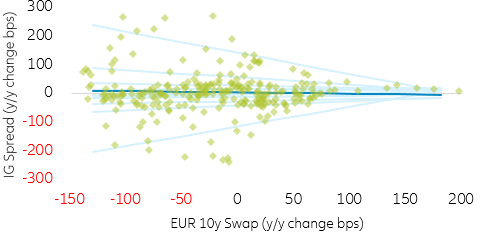

Figure 5: EUR IG vs EUR 10y swap quantile regression

Sources: Refinitiv, Allianz Research (Distribution split in 10 different quantiles)

*each light blue line indicates a different quantile regression, dark blue line refers to OLS

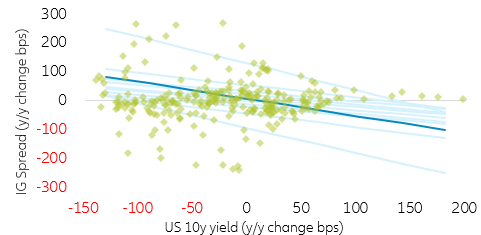

Sources: Refinitiv, Allianz Research (Distribution split in 10 different quantiles)

*each light blue line indicates a different quantile regression, dark blue line refers to OLS

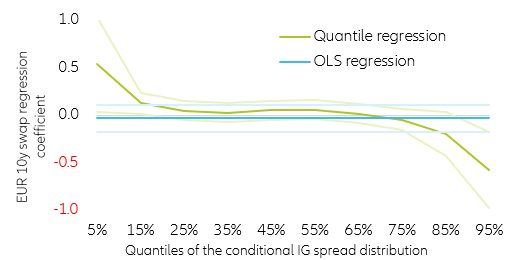

Looking at the coefficient throughout the quantiles, the picture becomes clearer: Most of the time (15 to 85% quantile), changes in long-term EUR nominal yields have no impact on EUR investment grade corporate spreads. Nonetheless, at the extremes of the spread distribution, things change. If spreads are in an extremely low environment (i.e. -200bps y/y change), the implied nominal yields coefficient is positive. In other words, falling yields translate into compressing spreads and vice versa. However, on the other side of the spread distribution, that is to say in large spread-widening environments (i.e. 100bps y/y change), the coefficient turns negative. This translates into declining long-term yields being consistent with widening corporate spreads, which is consistent with a flight-to-safety rotation (i.e. depending on the position within the distribution moves in yields can push spreads up or down) (Figure 7).

Figure 7: EUR 10y swap coefficient vs IG spread quantiles

Sources: Refinitiv, Allianz Research

*light colored lines indicate confidence intervals

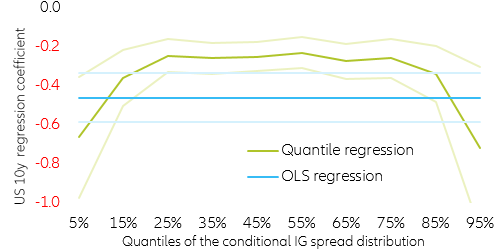

Figure 8: US 10y coefficient vs IG spread quantiles

Sources: Refinitiv, Allianz Research

*light colored lines indicate confidence intervals

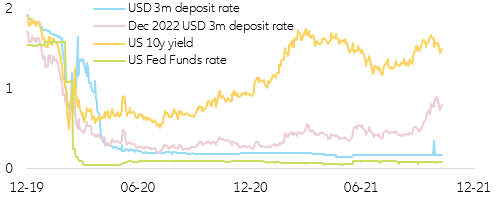

In this regard, we currently do not expect long-term sovereign yield interest to experience overly strong volatility in the coming months. The current flattening pattern suggests that, independent of the exact timing, market participants see monetary normalization to be moderate. The uncertainty about the persistence of current inflationary pressures and the monetary normalization path is therefore not feeding into the long end of the curve. This is also confirmed by the term structure decomposition of long-term sovereign yields: While the expectations component is on a timid upward trend (more in the US than in the Eurozone), the term premium as the main driver of yield volatility has stabilized, thanks to clearly communicated key rates and QE outlook (especially in the US). As long as central banks do not surprise by any emergency tightening measures, this stabilizing pattern should remain over the next quarters. Because of that, and since our base case scenario puts us right in the middle of both spread and long-term yields distribution, we expect a close to negligible effect on EUR investment grade spreads and US spreads.

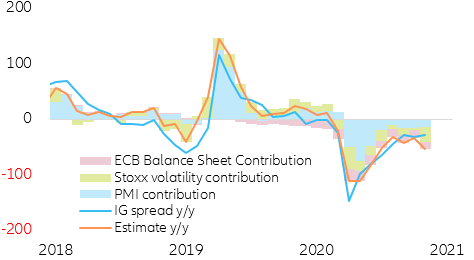

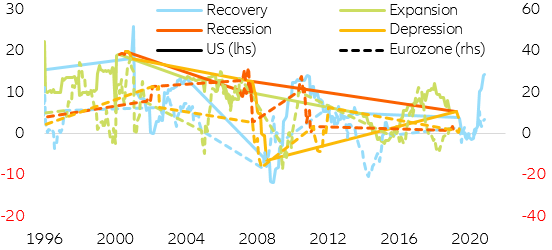

But are long-term yields all that matters? The combination of an economic component (represented by the Markit PMI), a market volatility indicator (represented by implied equity volatility) and the contribution of monetary policies (represented by the central banks’ balance sheets and/or the money supply growth) seems to better explain moves in investment grade corporate credit spreads both in the Eurozone and the US (Figure 9).

Figure 9: EUR investment grade spread decomposition (y/y change bps)

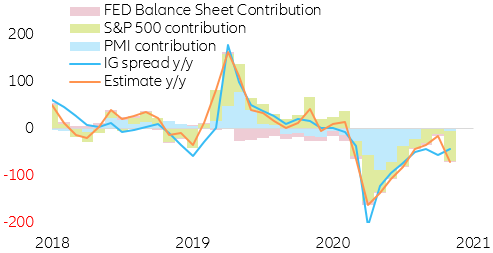

In the case of the US, the devil is in the details as it seems that US spreads’ reliance on equity volatility is far higher than that of the Eurozone, making them more vulnerable to changes in investor sentiment (it partly also leads economic sentiment as ultimately EUR and USD spreads are strongly correlated). At the same time, US spreads seem to be later in the cycle as the renewed economic tailwinds and the initial Fed intervention have been fully priced in, leaving spreads at an unstable equilibrium situation (Figure 10).

Figure 10: US investment grade spread decomposition (y/y change bps)

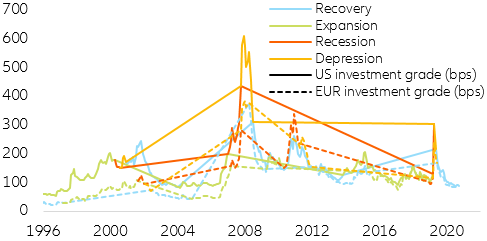

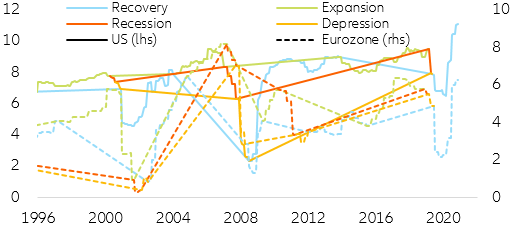

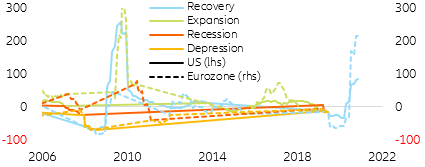

Figure 11: Investment grade spreads & business cycle (in bps)

Sources: NBER, ECRI, ICE BofA, Refinitiv, Allianz Research

* Business cycle phases defined as ½ distance using NBER peaks & troughs

** for the EUR aggregate French business cycles are used as it has the biggest weight in the BofA index

*** full line refers to US IG spread while dotted line refers to EUR IG spread

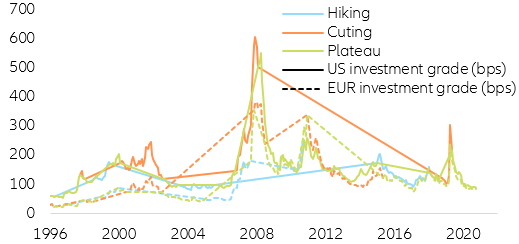

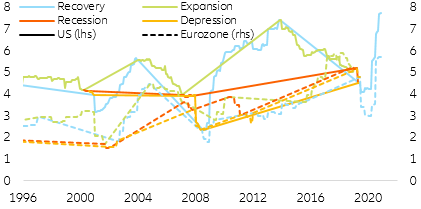

Figure 12: Investment grade spreads & monetary policy (in bps)

Sources: ICE BofA, Refinitiv, Allianz Research

* monetary policy cycle phases defined using last hike / cut

** full line refers to US IG spread while dotted line refers to EUR IG spread

Fundamentals also point towards market stability. Several fundamental valuation metrics are accompanying this stabilizing and recovering phase, with key credit cycle metrics showing signs of improvement and resilience. Along these lines, corporate debt to GDP is starting to decline as GDP growth recovers and corporate debt issuance slows down. This trend is consistent with other recovery and stability phases for corporate credit markets and hints towards a balance sheet consolidation phase. (Figure 13)

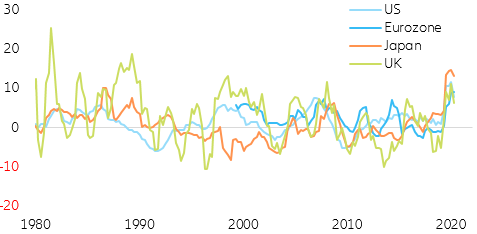

Figure 13: Corporate debt as a % of GDP (in y/y %)

Figure 14: Net profits margin (in %)

Sources: Worldscope, Refinitiv, Allianz Research

* full line refers to US while dotted line refers to Eurozone

Sources: Worldscope, Refinitiv, Allianz Research

* full line refers to US while dotted line refers to Eurozone

Sources: Worldscope, Refinitiv, Allianz Research

* full line refers to US while dotted line refers to Eurozone

Figure 17: Interest coverage ratio

Sources: Worldscope, Refinitiv, Allianz Research

* full line refers to US while dotted line refers to Eurozone

Figure 18: EPS market expectations (in %)