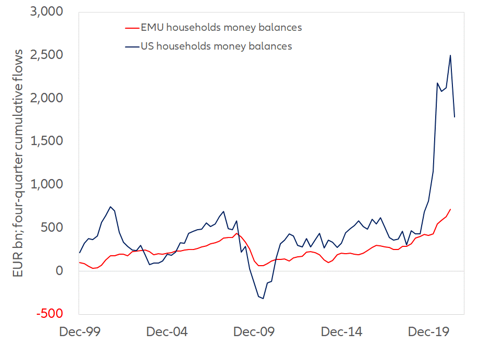

Figure 1 – Four-quarter cumulative change in households’ money balances in the US and the EMU

Money supply, saving & hoarding: What you see is not what you get

Figure 1 – Four-quarter cumulative change in households’ money balances in the US and the EMU

According to many an analyst, such an unusually large increase in privately held money balances indicates excess saving. The argument follows that when people tap into their savings, which they will inevitably do to correct the current excess, money balances will fall, unleash pent-up demand and a strong recovery will ensue.

As a matter of fact, one could (and actually should) deepen the excess saving argument by better distinguishing the two components of what laymen as well as some experts loosely call saving, namely:

- saving proper, or outlays other than consumption outlays,

- and (marginal) hoarding, or money not spent at all because it has been added to preexisting precautionary money balances.

If one hastily defines saving as that part of income that is not spent on consumption, one may be led to falsely believe that hoarding is part of saving, confusing money that is spent, but not on consumption, with money that is not spent at all. Focusing on the hoarding of precautionary balances, this investigation claims that the increase in outstanding money balances that inspires the excess saving argument systematically under- or overestimates the firepower set aside by private agents.

As a matter of fact, the excess saving argument underestimates by about 20% the quantity of money withdrawn from circulation and set aside by people in response to the Covid-19 shock. Saving proper has not really increased, but hoarding has, and much more than suggested by the cumulative increase in aggregate money balances since Q1 2020. Relevant to the growth and inflation outlook is the fact that the excess saving argument also underestimates the challenge of unleashing the purchasing power that people have stored for rainy days. The unlocking of hoarded money balances is not as straightforward as assumed by those who let the money supply alone guide their inflation expectations, at the risk of ignoring the demand for money. If people now held money balances above and beyond what they desire to hold, they would strive to get rid of excess liquidity and money velocity would increase. This has yet to happen. If there is something for policy to deter, it is hoarding; and if there is something to stimulate, it is saving.

Some money balances count more than others

On the one hand, at any time, the money supply consists of the money balances held by households, and of the money balances held by businesses. On the other hand, at any time, households and businesses have two motives to hold money balances: the transactions motive, and the precautionary motive.

It follows that the money supply can also be split into transactions balances (balances that do circulate because people and businesses pay their bills with them), and precautionary balances (balances that do not circulate because people and business hoard them as a precaution against a possible fall of their nominal income). For the sake of completeness, let us add that precautionary balances should be understood to include the money balances that people hold for speculative purposes. As long as people expect asset prices to fall further, such speculative balances do not circulate either.

The numerical example presented in Appendix A shows how we could directly measure transactions balances and precautionary balances

(or aggregate hoarding). It defines marginal hoarding as an increase in precautionary balances and shows that such an outcome is possible even when aggregate money balances are constant. That hoarding can happen even when the money supply does not increase at all invites caution when interpreting increases in money supplies such as the ones observed in 2020. The dual nature of the money supply means indeed that a variation in the money balances held by households and businesses, an easy-to-observe phenomenon, may have two not-so-easy-to-disentangle causes: a variation in the demand for transactions balances, or a variation in the demand for precautionary balances, or a combination of both. Like it or not, we cannot draw any conclusion about the magnitude of hoarding from an increase in the money balances held by private agents, since we have two variables, but only one equation. If transactions balances have decreased, the mere increase in money balances underestimates the quantity of money set aside, or withdrawn from circulation, by private agents.

Appendix A further shows that hoarding causes money velocity to fall and that, to quantify marginal hoarding, one needs to estimate the demand for money. In what follows, we investigate the behavior of both money velocity and the demand for money since early 2020.

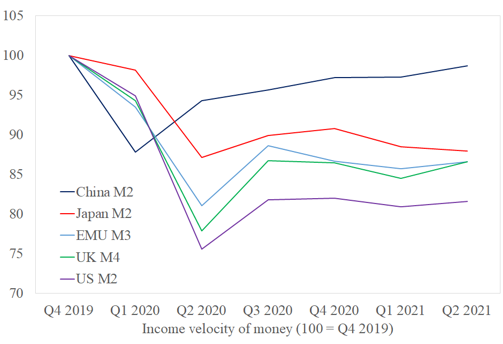

Hoarding leaves an unmistakable footprint on money velocity

If hoarding can occur even when the money supply does not vary, a fortiori can it occur when, as seen since early 2020, the money supply does increase. As we have just seen, we can infer from the decrease or increase of money velocity whether hoarding or dishoarding is happening. The sharp decline of money velocity in the early stages of the crisis, its limited recovery in Q3 2020, and its stability ever since indicate that hoarding, rather than saving proper, has been and remains the hallmark of the current economic and monetary environment.

Hoarding (or dis-hoarding) indeed leaves an unmistakable footprint on nominal spending and money velocity. To see that, let us start from Newcomb-Fisher's equation of exchanges, which says that nominal spending (a flow of money) equals the money supply (a stock of money) times its velocity, that is, how frequently money changes hands during a given period.

In a perfect world, we should tally all transactions: the transactions on final goods and services that make (nominal) GDP as well as transactions on intermediate goods and services, and securities transactions. At the risk of neglecting the transactions settled with bank notes and coins (for a large part, the money of the black economy), the sum of the debits on bank accounts during a given period could provide an estimate of aggregate nominal transactions. With that, economists could compute the transactions-velocity of money. For lack of such comprehensive measurement, economists are content to take nominal GDP as a proxy for aggregate nominal transactions and to compute the income-velocity of money (the ratio of nominal GDP to the money supply). Such is the approach followed in the present investigation.

Figure 2 – Income-velocity of money in major economies since Q4 2019 (=100)

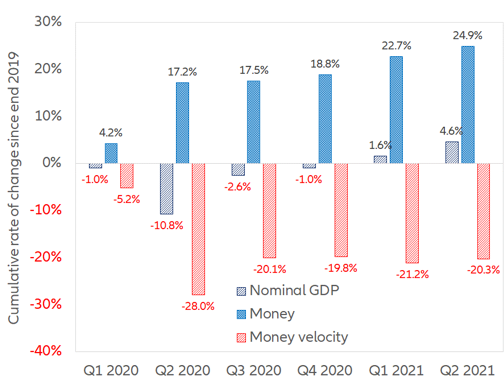

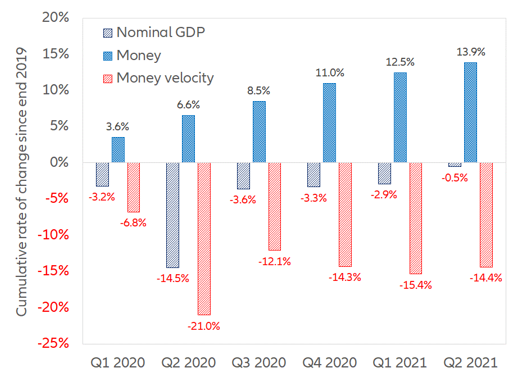

As we mentioned above, according to the Fisher-Newcomb equation of exchanges, nominal spending equals the money supply times its velocity. It follows, as shown in Figures 3 and 4, that the rate of change of nominal spending equals the rate of change of the money supply plus the rate of change of money velocity. If, as it has been the case since Q4 2020, money velocity is more or less constant, the rate of change of nominal spending roughly equals the rate of change of the money supply. What has then enabled the money supply to grow?

In our fractional reserve banking systems, “loans make deposits”; money creation depends on the banks’ willingness and ability to lend as well as on their clients’ willingness and ability to borrow. Since the outbreak of the Covid crisis, the bulk of the increase in central banks’ and commercial banks’ assets has stemmed from an increase in their claims (loans proper and bond purchases) on governments. Put differently, combining easy monetary policy with fiscal expansion has been and still remains the recipe that has enabled money supplies to grow. Confident, if not exuberant, expectations have not done it, yet.

Figure 3 – Cumulative rates of variation in nominal GDP, the money supply and money velocity in the USA since end 2019

Economists are not short of plausible explanations of its long-term downward trend. With long-term interest rates being as low as they are, the opportunity cost of holding money balances is in turn low. More generally, the prices of all kinds of financial assets being as elevated as they are, people may rather hold cash than risky assets. An increasing concentration of income and wealth in a few hands could increase the velocity of money in asset markets, but not necessarily in the markets for goods and services.

The link between inflation expectations and money velocity is a typical chicken and egg problem that may involve positive feedback loops. Like short-term inflation expectations, long-term inflation expectations tend

to be backward-looking. But on top of that, despite the recent acceleration of inflation, they are still low and rather inelastic. Alongside a rising sentiment of economic insecurity, subdued long-term inflation expectations may incite people to cling to their money balances.

A thorough discussion of the long-term decline of money velocity is beyond the scope of this investigation, the subject matter of which is the cyclical fluctuations of money velocity around its long-term trend.

In the shorter term, money velocity increases when people hold more money balances than they desire and strive to get rid of excess liquidity.

A policy that would aim at pushing up the velocity of money, a policy for that matter still unconventional, should therefore ensure that the supply of money exceeds its demand. This may require some continued coordination between monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Failing such a nudge, the unleashing of the money set aside (hoarded) in 2020 is unlikely to happen and we will be waiting for Godot. The recent discrepancies between the money supply and the demand for money are too small to generate significant fluctuations of the velocity of money and, by the same token, of nominal growth.