EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

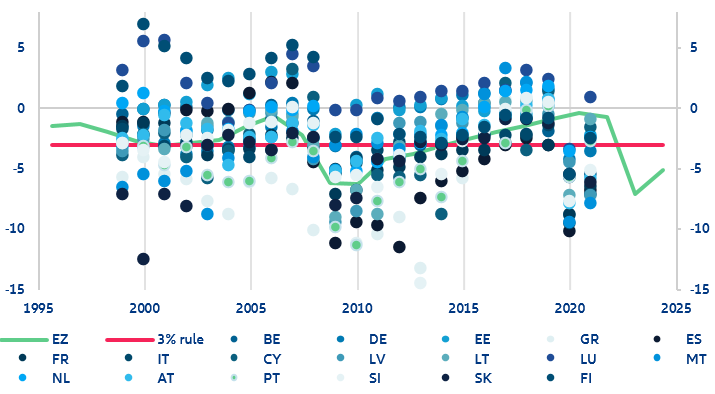

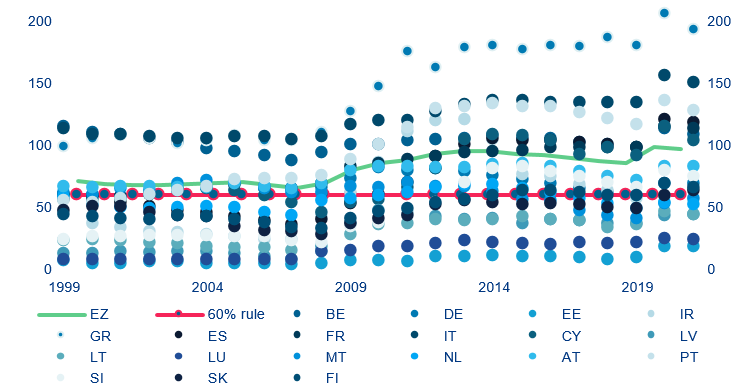

- In the coming days, the European Commission is expected to propose the most ambitious overhaul of the EU fiscal framework in more than two decades. Given the rapid rise in debt ratios during the pandemic and the current energy crises, the application of the current rules, which are currently suspended, would require unrealistically large – and counterproductive – fiscal adjustments by some high-debt countries. The key points that need to be addressed include the pro-cyclicality and complexity of the EU fiscal framework, as well as its lack of transparency, its inability to differentiate between growth-enhancing and other public spending and lackluster enforcement. While the general budget and debt rules (3% of deficit-to-GDP and 60% of debt-to-GDP) are expected to remain unchanged – not least to avoid time-consuming and politically charged treaty changes – there seems to be a general preference for country-specific multi-year net expenditure paths with built-in flexibility for countries investing in priority areas (in return for stricter oversight and stronger enforcement). Reducing the number of multiple, potentially conflicting operational targets is also likely to improve transparency and compliance.

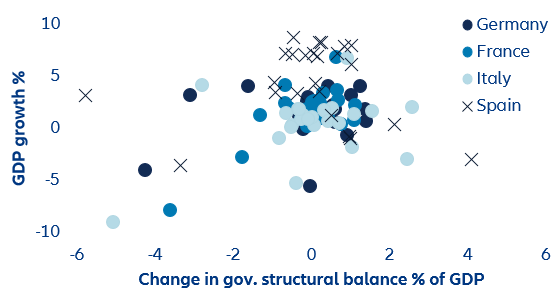

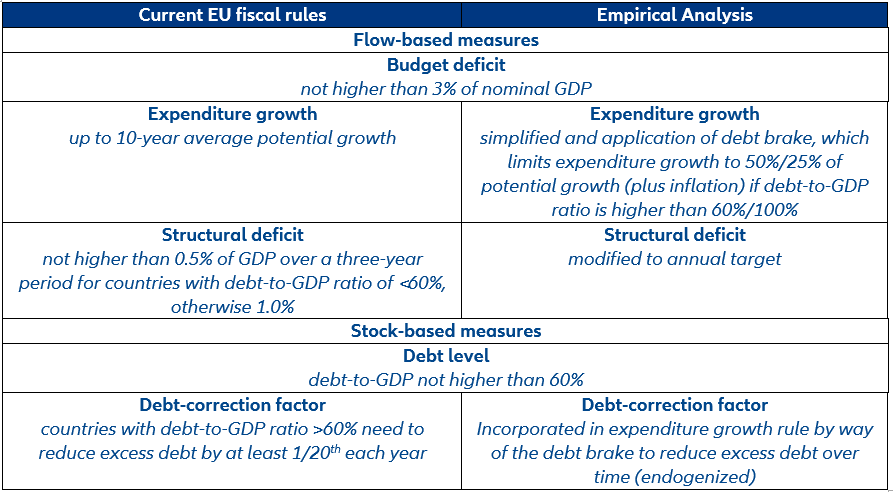

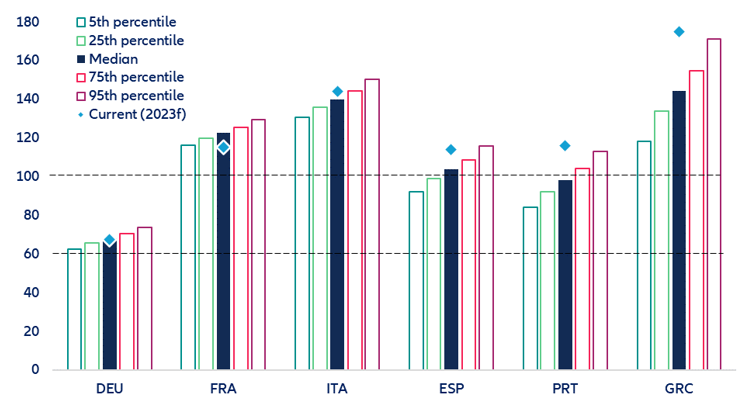

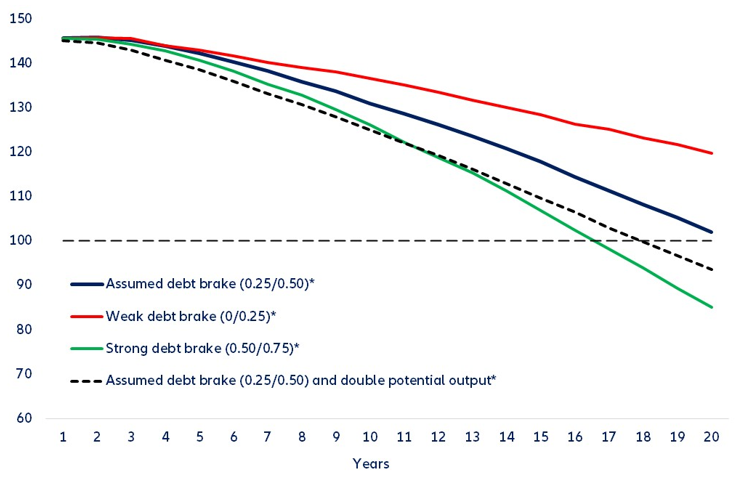

- Our simulation results suggest that a simplified expenditure rule can significantly reduce the pro-cyclicality of current fiscal rules while guiding growth-friendly fiscal policy towards a credible debt path. A pragmatic expenditure growth rule—if combined with a debt-brake mechanism—can provide more flexibility to country-specific circumstances, including a longer time window for fiscal adjustment. We find that most countries would be able to reduce their debt-to-GDP ratios by at least 10pps over the next 10 years, but only Germany in our sample will be able to meet the critical threshold for a debt-to-GDP ratio of 60%. Large interest rate shocks would slow the pace of debt consolidation, especially for France, and to a lesser extent for Italy and Spain, but less than under a structural deficit target governing the fiscal stance. In addition, an expenditure rule can significantly lift real growth by up to 0.2pp on average in the largest Eurozone economies and up to 0.6pp for Greece and Portugal (compared to alternative rules). In contrast, compliance with a structural balance rule would come with a high degree of uncertainty about debt consolidation over the longer term, especially during times of high interest-rate volatility.

- Reforming the fiscal rules should ideally be complemented by a permanent centralized fiscal capacity for stabilization and investment. Given the high debt levels in most Eurozone countries, structural pressures will constrain fiscal space at the national level, especially in the most vulnerable economies. Since current investment plans at the national level still seem to fall short of actual investment needs, setting up a central fiscal capacity could be a viable alternative by (i) providing incentives for compliance with the fiscal rules if access is made contingent on compliance, (ii) boosting public investment in the EU and (iii) enhancing Eurozone resilience.

An urgent need to reform

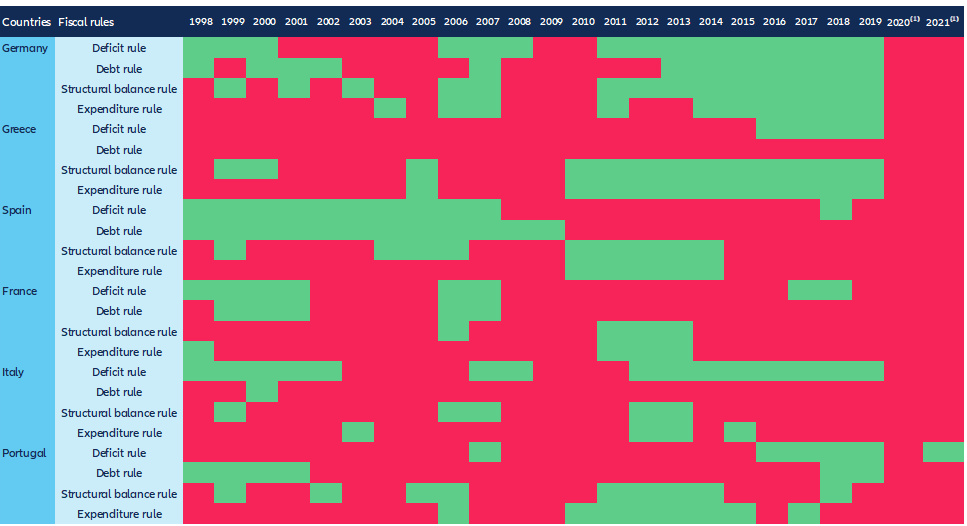

There is widespread recognition that the EU fiscal framework needs to be reformed. While monetary policy in the Eurozone is fully centralized, fiscal authority rests mostly with national governments. Thus, the EU adopted fiscal rules under the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 to coordinate fiscal policy across member states to ensure sound public finances, and in turn safeguard fiscal sustainability within the currency union. However, surging public debt since 2007 amid significant cross-country heterogeneity suggests that current fiscal rules are no longer fit for the purpose and need to be reformed. The current framework involves an intricate set of constraints, which complicate effective monitoring and public communication, and create risks of inconsistency and overlap between different parts of the system. As a result, many high-debt countries failed to reduce their debt ratios in the years preceding the pandemic, despite relatively robust growth.

Figure 1: Pro-cyclical nature of EU fiscal rules (%)