EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

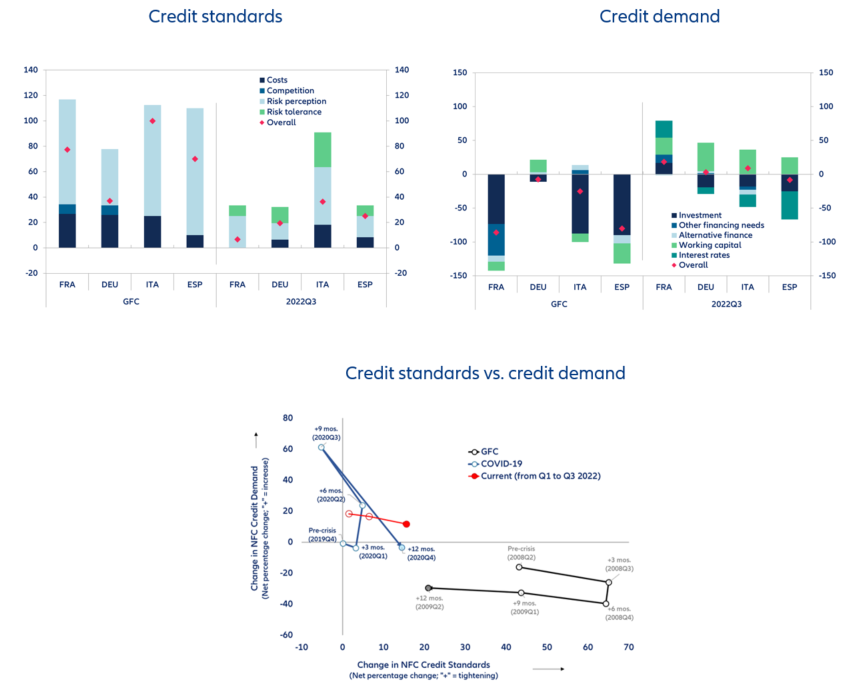

- Against the background of rising interest rates and a worsening economic outlook, still favorable credit dynamics in the Eurozone are unlikely to last for much longer. After a year of stabilizing lending standards, banks have become significantly more risk averse. Credit standards are likely to tighten further as banks’ declining risk tolerance, the higher cost of funds and balance-sheet constraints will affect credit supply over the next few months. The extent of net tightening is similar to levels recorded during the early stages of the Covid-19 crisis in 2020.

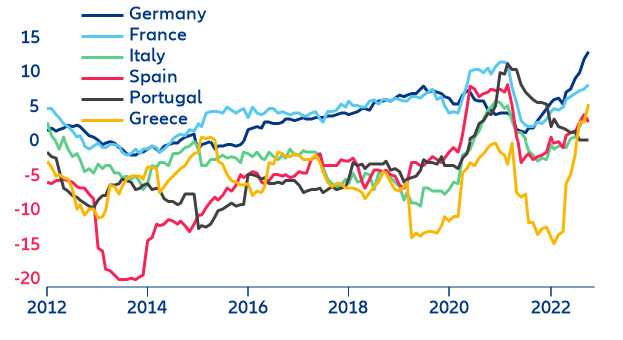

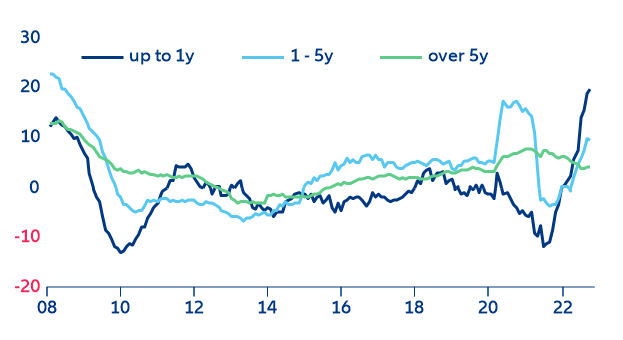

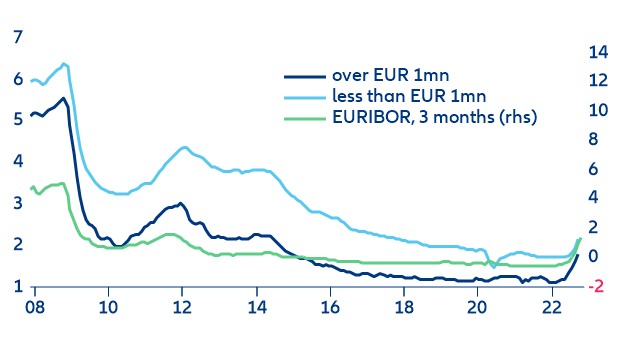

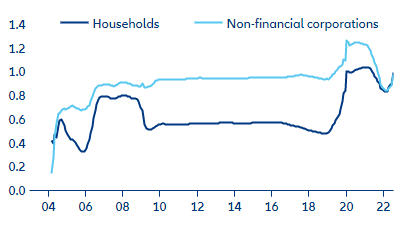

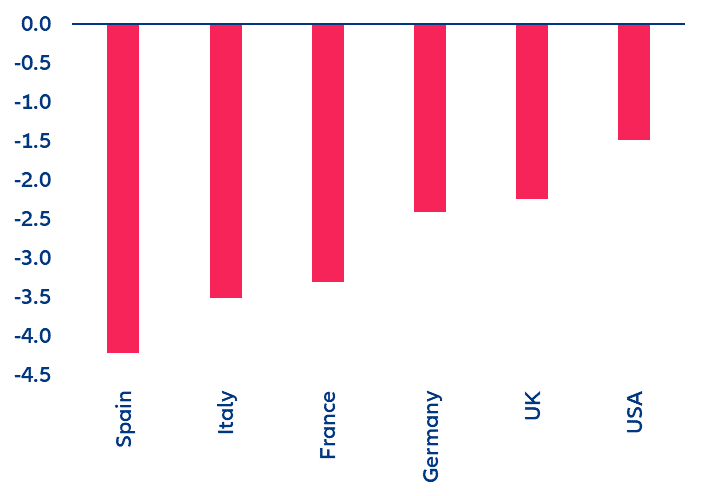

- For companies, we expect an average increase in interest rates by +200bps in the first half of 2023. Looking ahead, the rise in non-financial corporates’ financial debt to new records in absolute terms, combined with the global tightening of financial conditions, are set to intensify interest expenses and to add to companies’ costs. We forecast that further increases in the policy rate would raise average interest rates for corporates by an additional 200bps by mid-2023, which in turn will cut firms’ margins by more than -3pps. Italy, Spain and France are most at risk. However, note that more than 50% of corporate loans increased their maturity to above five years, with less than 20% below one year.

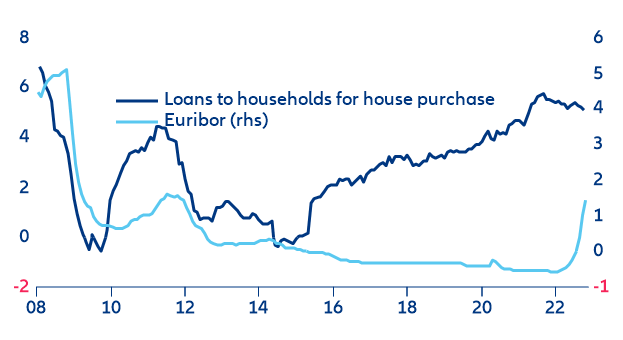

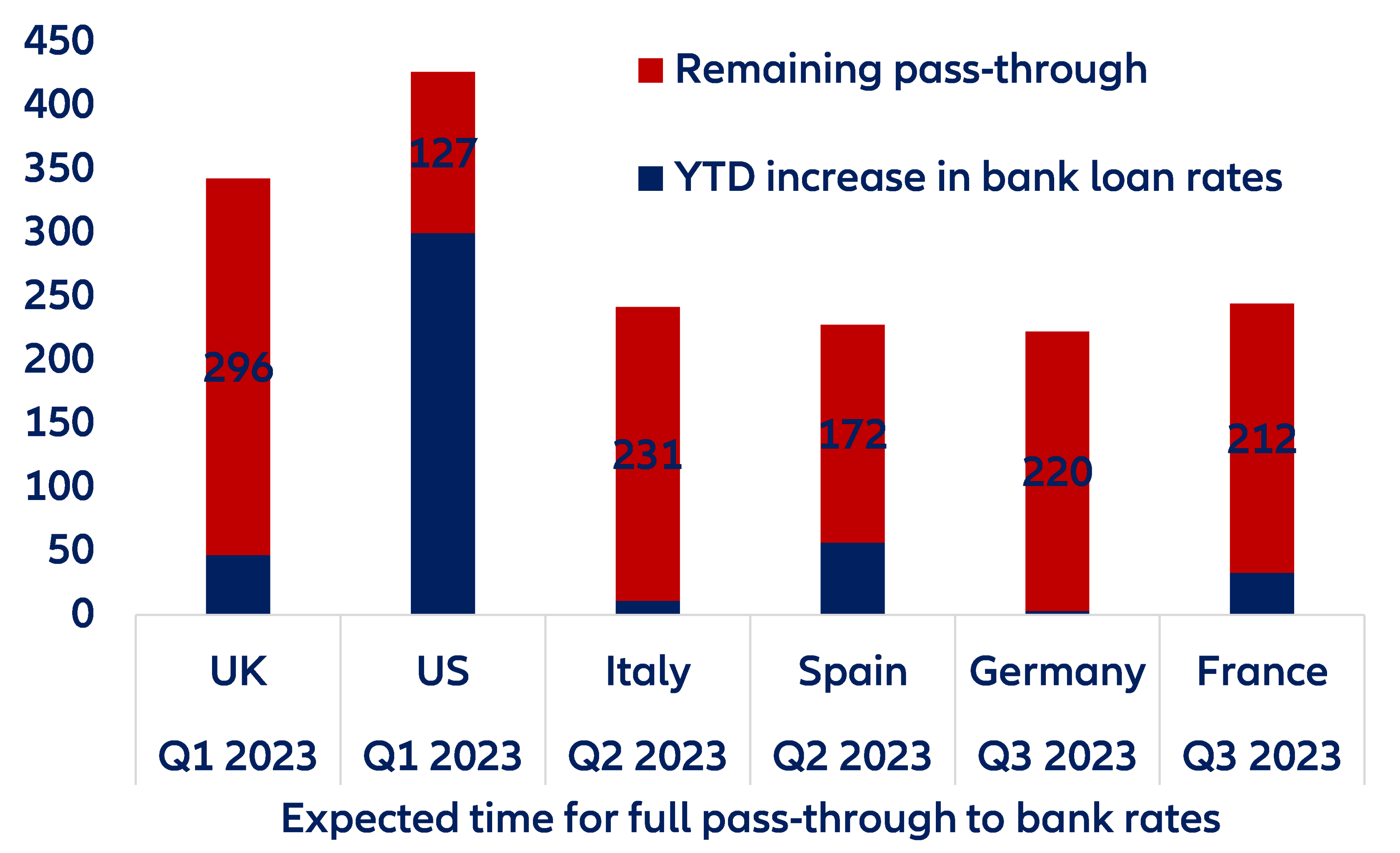

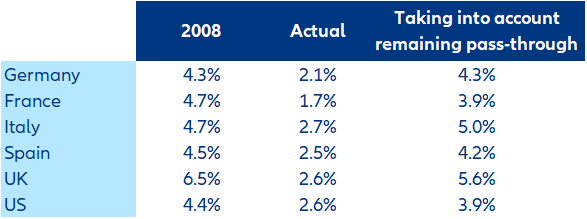

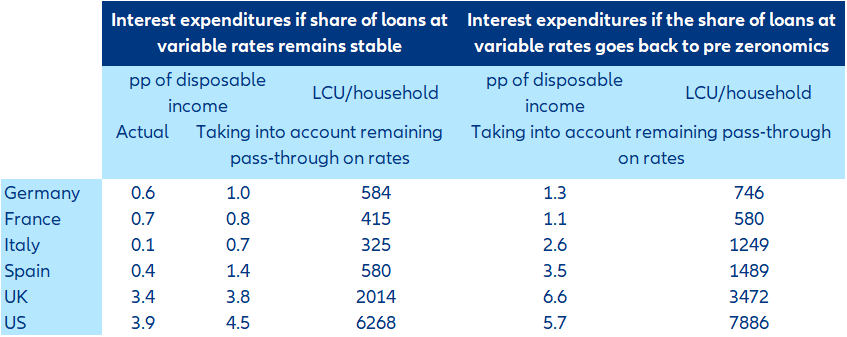

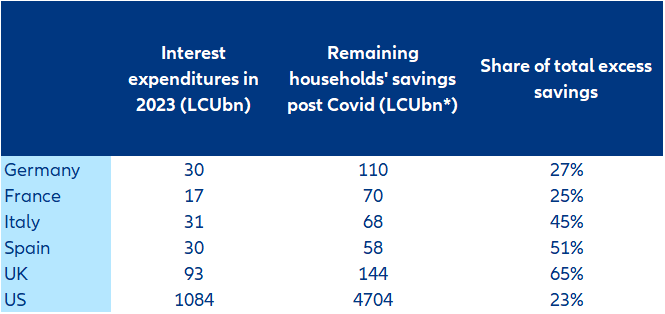

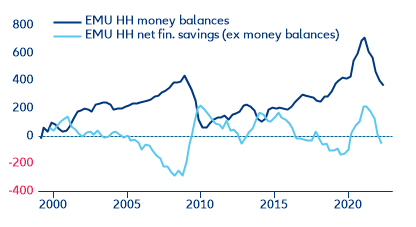

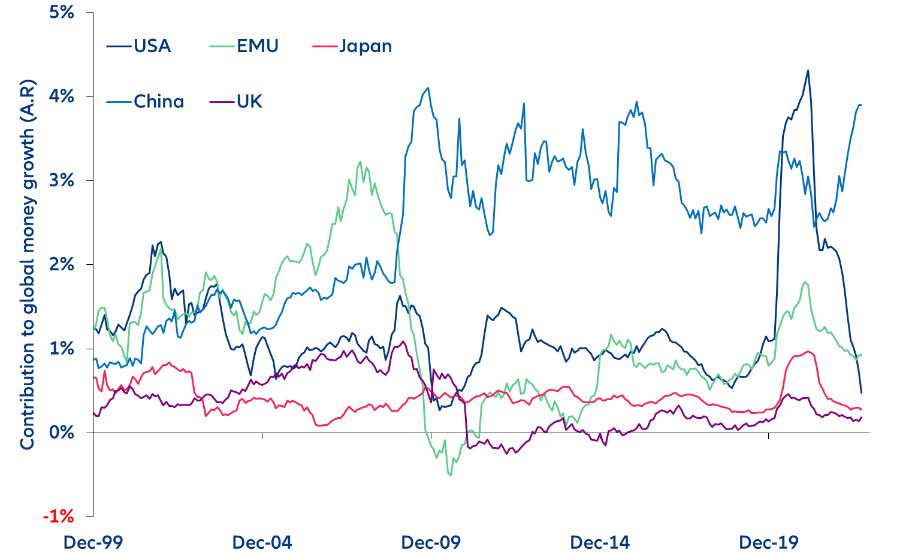

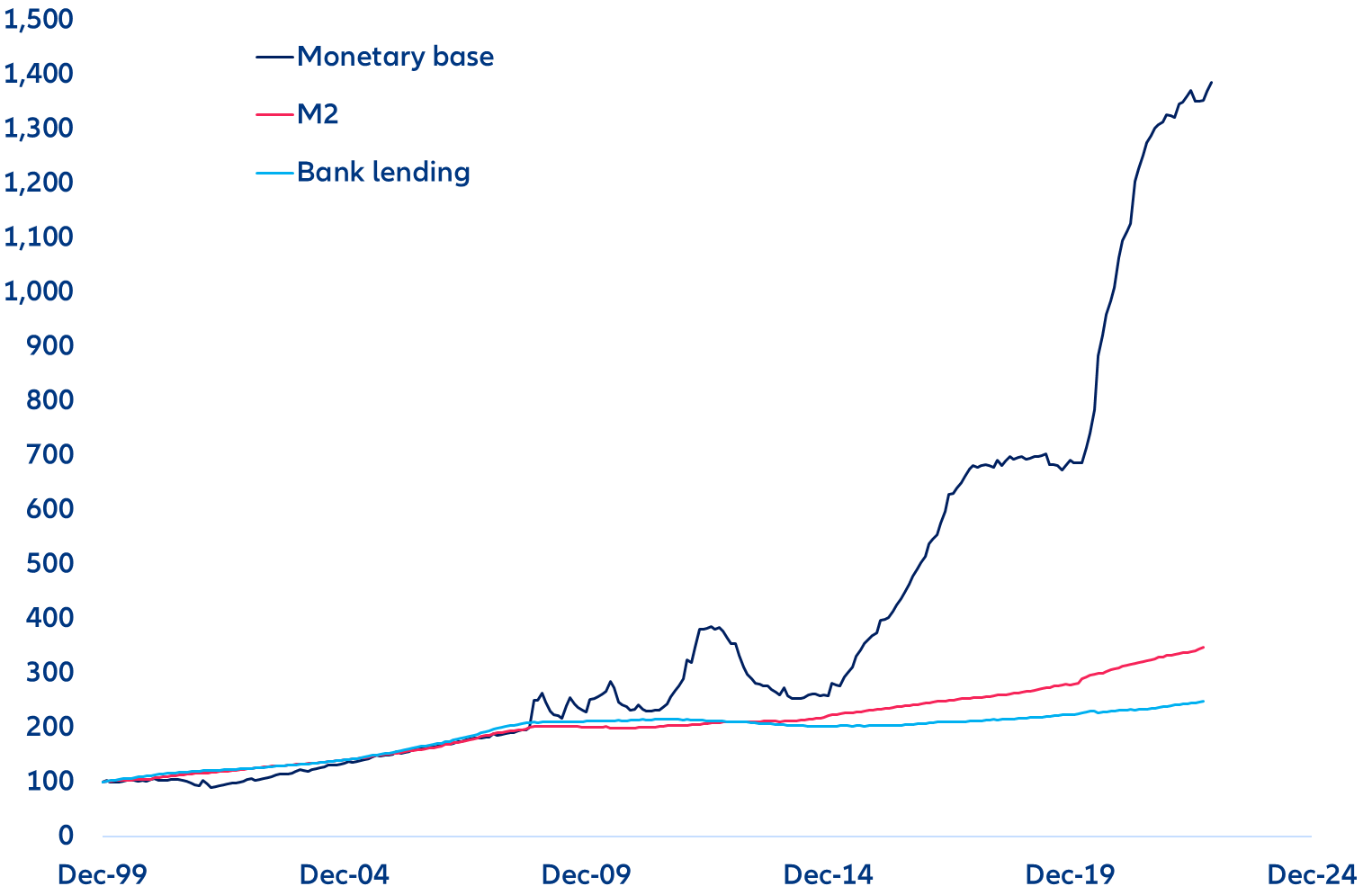

- For households, the interest rate pass-through is likely to reach 210bps on average. This shock could be partially compensated by excess savings related to Covid-19 and precaution. Looking at the share of loans at variable rates (i.e. less than 10% of total loans against close to 40% before 2012), we estimate that the loss in terms of Eurozone household purchasing power will stand at -1pp on average, equivalent to close to EUR500 per household. Interest expenditures in 2023 would represent around 20% to 30% of total post-Covid savings in Germany and France, 45% in Italy and more than 50% in Spain. Overall, despite a high inflation rate, the velocity of broad money remains well below its pre-Covid level, which means that the bulk of the increase in money supply has been absorbed by a higher demand for precautionary balances (i.e. money that does not change hands, as opposed to transactions balances).

Eurozone credit demand has remained strong, but banks are getting worried.

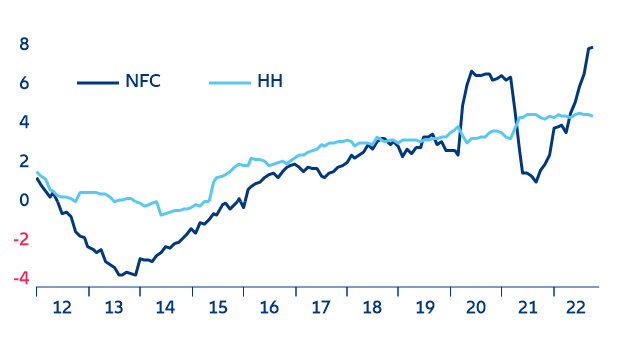

Despite rising interest rates and a deteriorating economic outlook, credit dynamics have remained favorable in the Eurozone - but not for good reasons (Figures 1-5). Overall annual credit growth to the private sector averaged at +5.7% in September. Lending remained particularly strong for firms (at +8.9% y/y in September), especially for shorter maturities as surging energy and raw material prices increased companies’ working capital requirements. Conversely, loan demand by firms over the longer term has markedly slowed as uncertainty about the energy crisis and the potential for renewed supply-chain disruptions have dented business prospects. Declining business confidence has also dampened firms’ net demand for loans to finance investments. At the same time, declining consumer confidence and a softening housing market have weighed on household borrowing during the last quarter.

Figure 1: Eurozone - credit growth to private sector (y/y %)