We now expect the bipartisan deal to agree on a modest net fiscal tightening (against our previous expectation of a modest net easing), amid more political divisions within the Republican party. Conservatives fiercely oppose government spending increases, so it would require at least some spending cuts agreed upon with the Democrats to get them to sign the deal. Fiscal tightening reinforces our call that the US economy will muddle through a recession this year, albeit a moderate one (we expect a -0.3% GDP drop).

Elysée Treaty 60th anniversary—recharging the Franco-German partnership to respond to the energy challenge and lead an imperiled Europe?

On Sunday, France and Germany will celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Elysée Treaty, which aims to strengthen the cooperation between the two nations after centuries of rivalry and conflict. However, the anniversary gives little reason to celebrate. Recent months have been marked by rising political tensions between the EU’s largest economies, which culminated in the cancellation of a Franco-German Council of Ministers in late October. Yet, with war raging just a few hundred miles away from Berlin, the very genesis of the Treaty has become an obligation for both countries to reaffirm their shared values in shaping Europe’s response to its multiple crises.

On the occasion of the anniversary, both countries have pledged to set out a common roadmap, which could provide a common vision and strategy for both countries but also more broadly for Europe. Beyond PR and wishful thinking, observers will especially be looking for common positions on topics that were divisive in 2022, ranging from more integrated energy systems and closer security cooperation to common industrial and trade policy.

One area of focus is likely to be how both countries can from a unified response to the US Inflation Reduction Act, which has already been discussed at the recent Franco-German economic and financial council meeting. There is shared concern on both sides of the Rhine that US subsidies could draw European companies to the US, in particular by the IRA’s most important provisions, such as its incentives for electric vehicles and zero-carbon electricity, which are “uncapped” tax credits and could reach up to USD800bn according to recent estimates. After considering the amount of private investment federal spending tends to catalyze, the IRA could boost total climate spending to roughly USD1.7trn over the next 10 years (almost twice the size of the EU’s Green Deal, which was announced with great fanfare three years ago).

The EU’s immediate response to the IRA has focused on seeking exemptions from the discriminatory clauses. It has attempted to do so by using the threat of a counter-subsidy package, which is unlikely to be effective as leverage. The European Commission has been given a mandate to come up with a plan early this year, which seems to include a further relaxation to the Temporary State Aid framework to facilitate scaled-up government support to key industries and technologies.

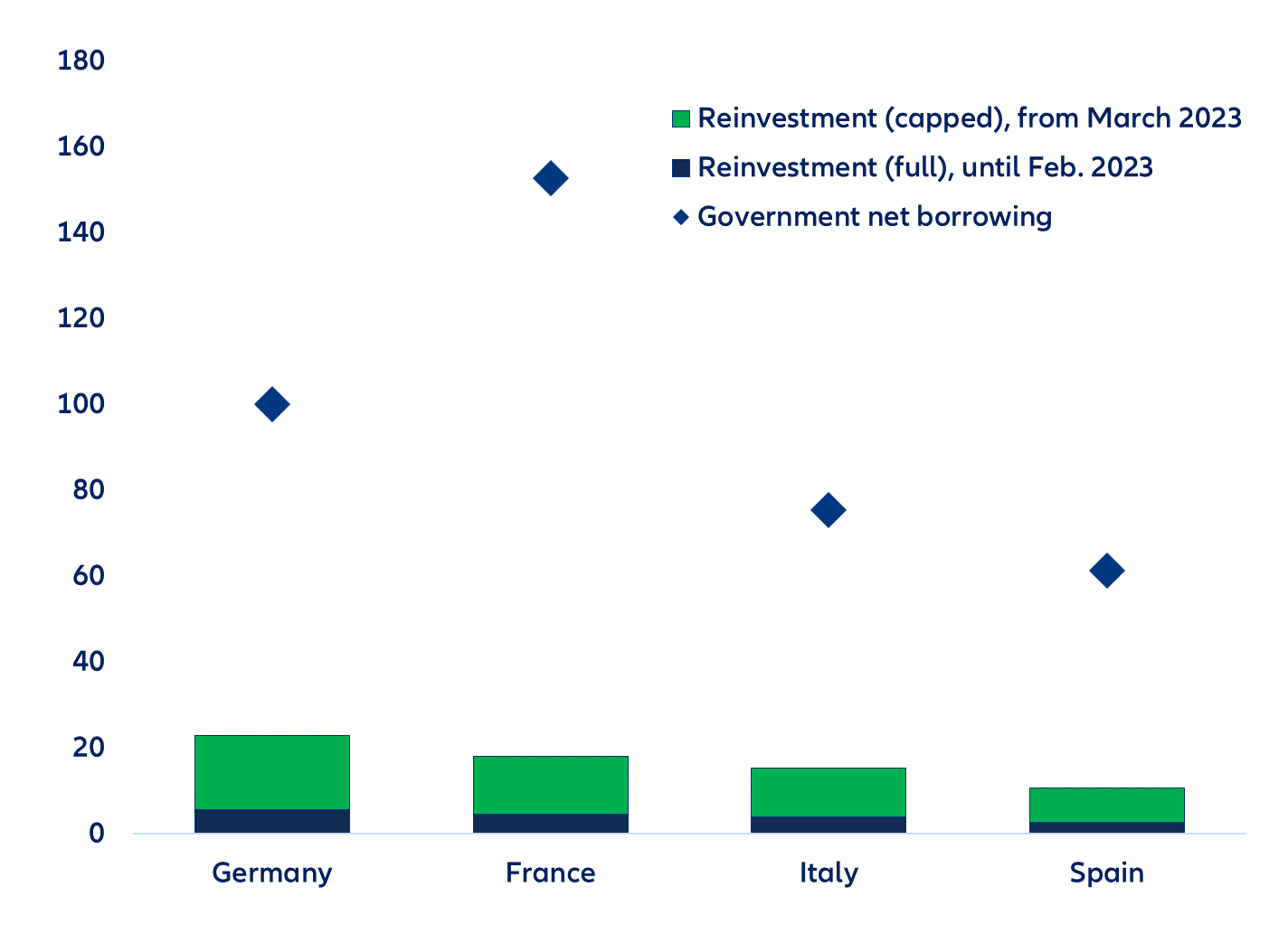

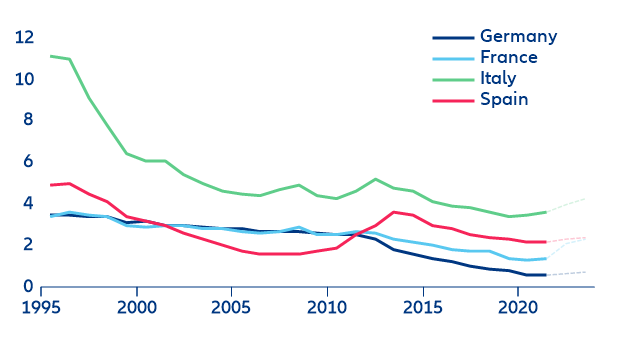

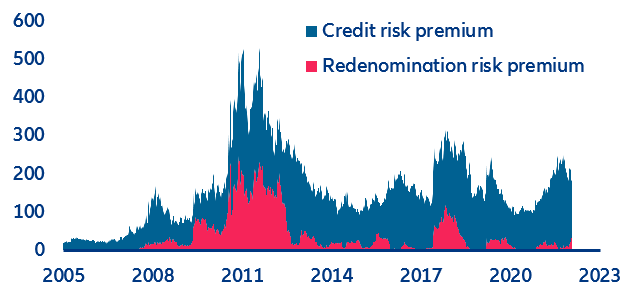

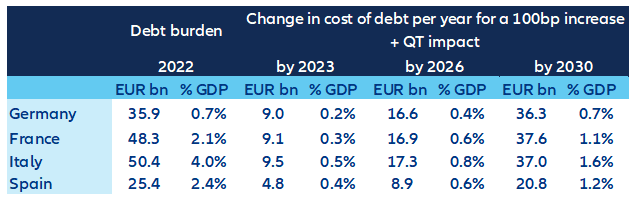

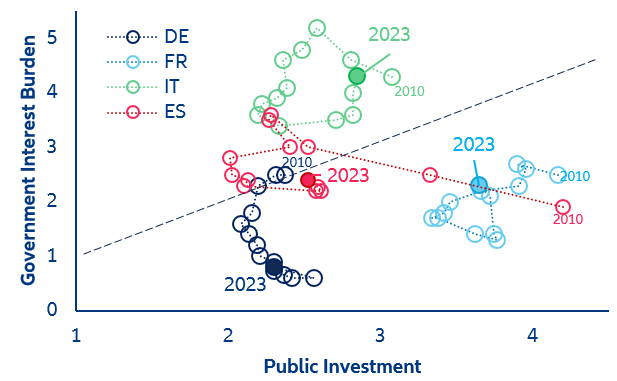

Enhancing the EC’s central fiscal capacity would be another plank of the EU strategy at a time when tightening financing conditions will constrain fiscal space in supporting climate-smart public investment. In our recent research, we found that, except for Germany, the largest Eurozone economies are already struggling to stabilize elevated government debt levels. As we show in this week’s feature (see below), even if government debt ratios remained unchanged, a lasting interest-rate shock (reflecting the ECB’s current hiking cycle) would mean that interest expenses will amount to 2% GDP in these countries by 2030. To put these figures into perspective, this additional budget burden due to higher financing costs alone exceeds total public investment.

Insolvencies in construction leading the global rebound

Rising insolvencies since last year are now affecting also large companies. According to our internal reporting, while business insolvencies massively concern SMEs, insolvencies of large firms, those with over EUR50mn of turnover, posted a noticeable rebound at the end of 2022 globally. In Q4 2022, the number of major insolvencies surged by +30 cases compared to the previous quarter, and +17 compared to Q4 2021, to reach 88 companies. This is a record high since Q4 2020 and slightly above the pre-pandemic average (74 over the period 2015-2019).

We expect larger insolvencies to remain broad-based but there are geographical (Europe) and sectoral (construction, retail) pockets of higher vulnerabilities. Globally, major firms benefit from larger cash buffers and higher pricing power, but the global context of slower macroeconomic growth, weaker financing conditions and specific issues (e.g. energy mix, supply-chain dependencies, FX, Covid-related policies) is increasing the risks for the earnings and cash flow of the most vulnerable ones, notably those most indebted or with a low-profit business model. In Q4 2022, all regions contributed to the rebound in major insolvencies, but Western Europe already stood out with the largest increase (+15 cases q/q to 46), ahead of Asia Pacific (+6 cases q/q to 22) and North America (+6 cases q/q to 11). The full-year outcome has almost the same ranking, with Western Europe registering more than half of the global count (138 cases out of 270) ahead of Asia (70), Central and Eastern Europe (32) and North America (27). China continues to post the highest number of top insolvencies, with nine out of the top 10 insolvencies in terms of turnover for 2022, including seven firms in the construction sector due to the real estate downturn. Globally, construction has already proved to be the most affected in 2022, with 64 major insolvencies (+17 cases compared to 2021), notably in Western Europe (30 cases) and Asia (24). In the last quarter, however, retail recorded the largest increase in major insolvencies, ahead of construction, metals (esp. in Western Europe) and services (esp. in the US).

Brazil: ready for a roller-coaster ride?

President Lula’s new term is off to a rocky start. But it is not vandalism by Bolsonaro supporters that is shaking markets so much as worries over the ballooning fiscal deficit. With Brazil's debt-to-GDP ratio at 88%, compared to an average of 45% in other major countries of the region, the recently approved BRL145bn (1.6% of GDP) spending package (known as Transition PEC) is putting the country's fiscal credibility at risk.

The beginning of the new administration has created some alarming points for investors: The decision not to privatize Petrobras and the upcoming change in fuel-pricing policy; contradictory statements from ministers, pointing to a lack of policy coordination; the extension of the federal tax exemption on fuel and Lula's conspicuous lack of comment on fiscal reform and debt management. As a result, Brazilian assets have not fully benefited of the positive mood in global markets. The financial sector and some of the big companies especially vulnerable to more interventionist policies have been the most affected (notably Petrobras).

In response to market stress, the government switched to a more conciliatory tone, and Finance Minister Fernando Haddad has taken measures to reduce the fiscal deficit in 2023 (estimated at 1.9% of GDP for now). But Brazil still has a long way to go. The measures focus mainly on the short term, focusing on increasing revenues rather than cutting expenses. Moreover, there is no guarantee the estimated targets are going to be achieved. In this context, we do not expect public debt to stabilize: it could reach close to 100% of GDP by the end of President Lula's mandate.

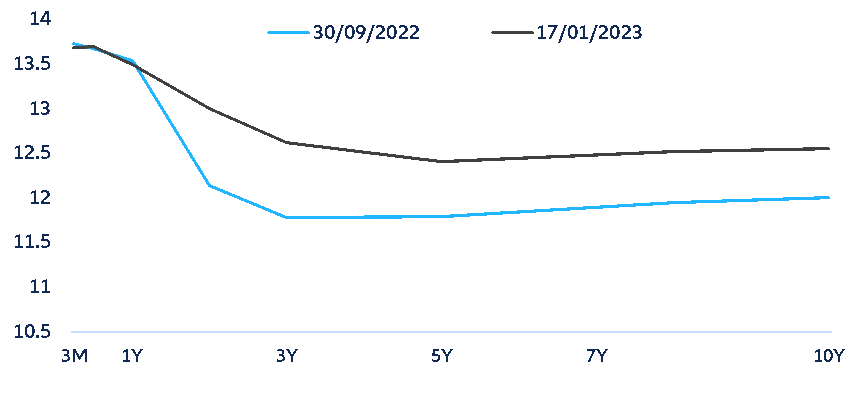

It is likely that the announcement was designed to give the government more time to work on a tax reform and a new spending cap rule, which could be announced in April, according to Minister Haddad, or no later than June). More structural measures like this will be fundamental to anchor expectations and leave room for the central bank (BCB) to reduce interest rates. A survey carried out by the BCB shows that markets have raised their inflation forecasts and foresee lower cuts for the Selic rate in 2023, clearly signaling markets' concern with a mismatch between monetary and fiscal policy. This has been observed as well in the movements experienced in the bond market where yields of medium and long-term maturities have move upwards since Q3 2022 (Figure 3), in dissonance with global sovereigns where the inversion has deepened, and the yields of long-term maturities have been stable or have fallen.

Figure 3. Brazil-BRL sovereign yield curve (%)