EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

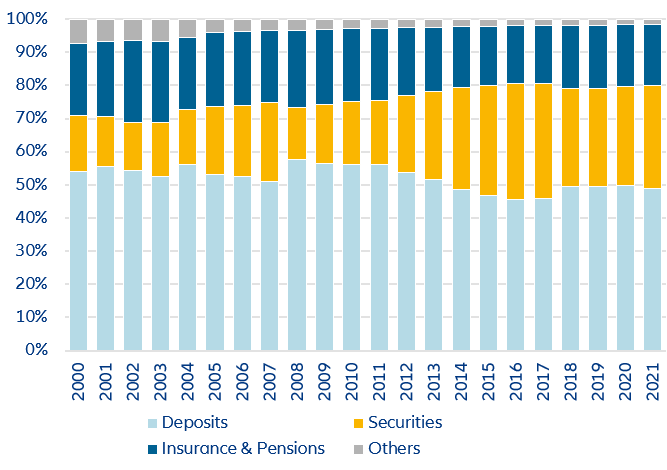

- Total gross financial assets in Asia reached a new record high, but the share of life and pension assets in private households’ portfolios kept declining. Total gross financial assets increased by +9.4% and reached a new record high of EUR62.4trn in 2021, 25% above the corresponding figure for Europe. However, the gradual decline of the share of life and pension assets continued: Since 2008, this has dropped by 5pps to 18.4%; in Europe, life and pension assets are almost twice as important.

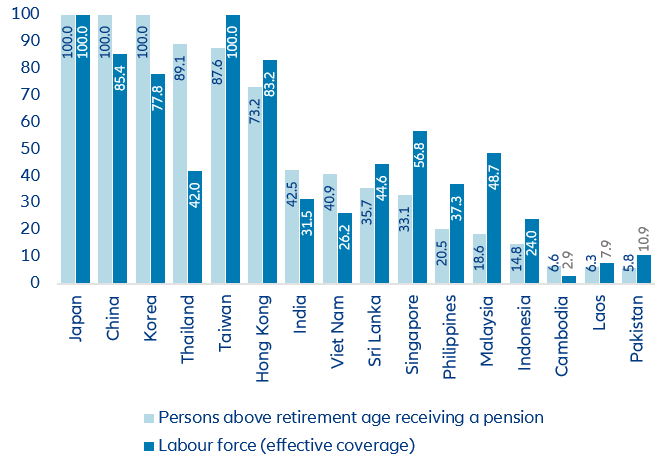

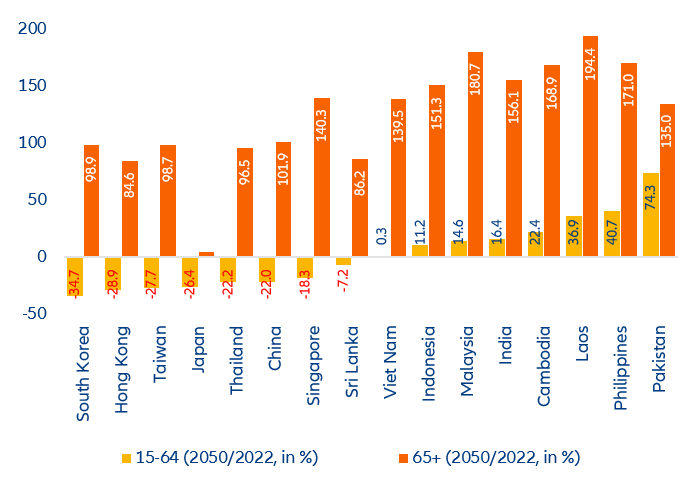

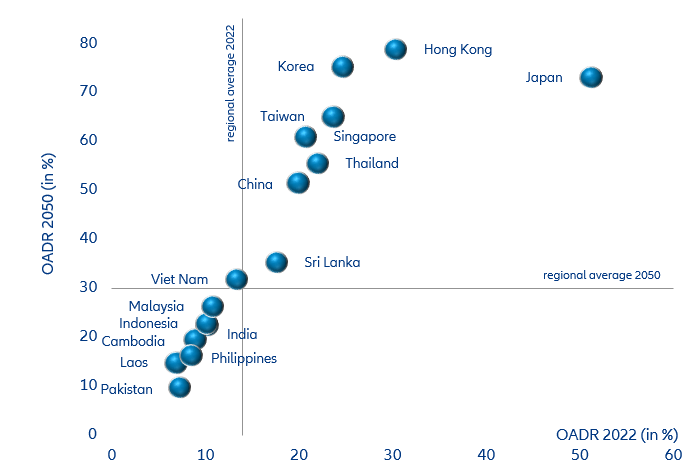

- Asia’s old-age dependency ratio set to more than double until mid-century. In Europe, the same demographic shift took almost 60 years. By 2050, 1bn pensioners will live in Asia. Supplementary capital-funded pension pillars have to play an important role in emerging markets as merely pay-as-you-go or tax-financed pension systems will not be sustainable in the long run.

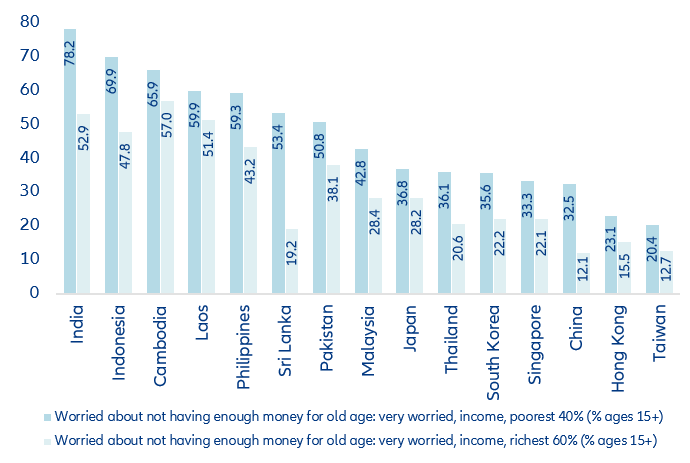

- Tax-incentives and subsidies to reverse the decline in popularity of private, capital-funded pension provision are essential. Moreover, Asia’s emerging markets have to increase their efforts to improve the accessibility of financial services and financial literacy. Both are essential for building up a capital stock and private pension provision.

Gross financial assets have hit a record high in Asia, but pension assets are not keeping up.

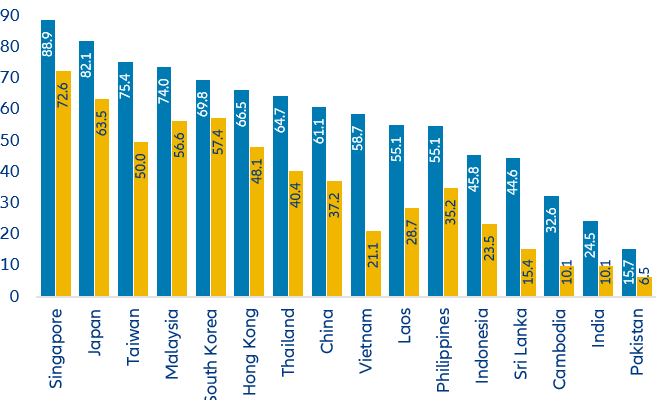

Total gross financial assets of Asia’s private households increased by +9.4% in 2021, reaching a new record high of EUR62.4trn. This corresponds to EUR16,380 per capita, compared to the global level of EUR41,890. China and Japan account for 75% of the region’s gross financial assets total, with China’s private households holding an estimated EUR31.8trn or 51%, while those in Japan hold EUR15.8trn or 25%. Ten years ago, the roles were reversed: Japan’s private households held 45% of the region’s financial assets and China’s share was 30%. What has not changed is their huge lead compared to the other countries in the region. Private households’ gross financial assets in the third-richest country Taiwan added up to EUR3.9trn, which corresponds to 6% of total assets, just ahead of South Korea, where they amounted to EUR3.6trn. Of the remaining countries, only India (EUR2.7trn) and Singapore (EUR1.0trn) reported gross financial assets above the EUR 1trn threshold. In the other countries, gross financial assets ranged from EUR702.4bn in Thailand to EUR24.7bn in Cambodia.

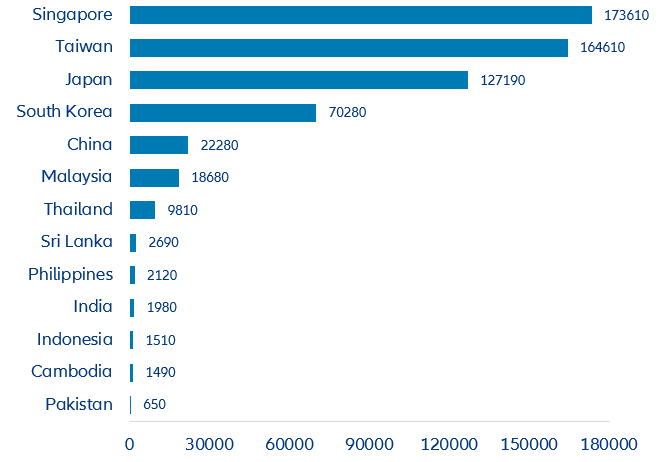

However, taking into account the population size highlights the wealth disparities within the region. In Singapore, gross financial assets per capita amounted to EUR173,610. In Taiwan, they reached EUR164,610 and in Japan EUR127,190. In South Korea, the fourth of region’s mature markets, gross financial assets per capita were EUR70,280, or about 40% of the value in Singapore. China, Malaysia and Thailand make up the midfield in this ranking, with gross financial assets per capita amounting to EUR22,280, or merely 13% of the average financial wealth of a Singaporean in China; EUR18,680 in neighboring Malaysia and EUR9,810 in Thailand. In the remaining Asian countries, gross financial assets per capita were markedly below the EUR5,000 threshold. That means that even though the gap between the richest and the poorest in terms of gross financial assets per capita has almost halved since 2010, individuals in Singapore have 265 times the average financial assets per inhabitant in Pakistan. Moreover, convergence has slowed since 2019 and even reversed in 2021 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Gross financial assets per capita