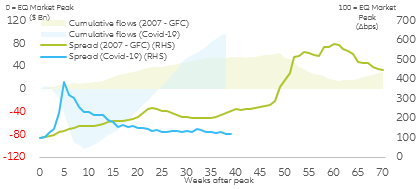

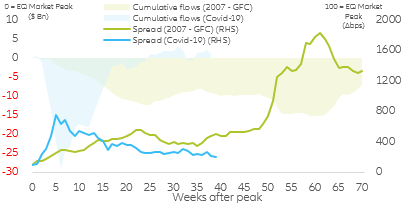

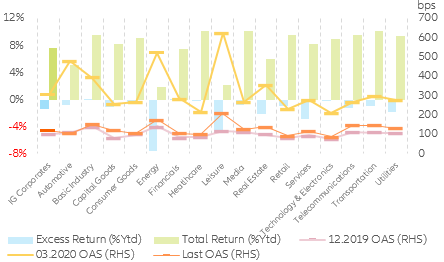

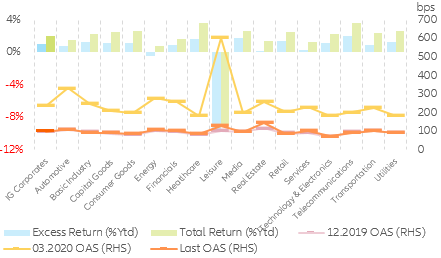

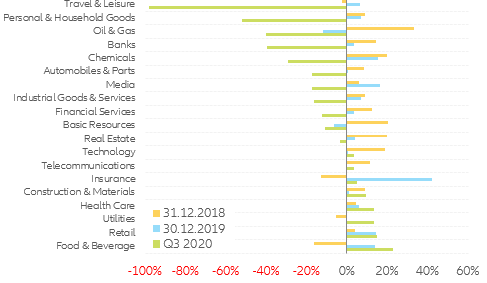

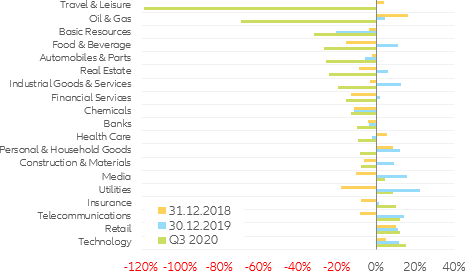

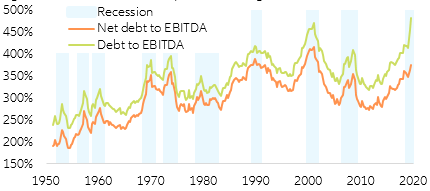

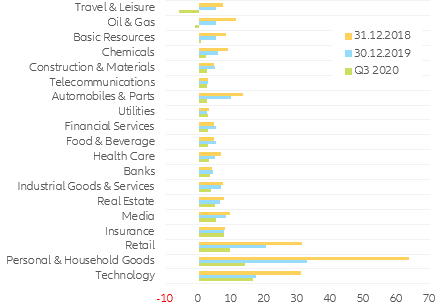

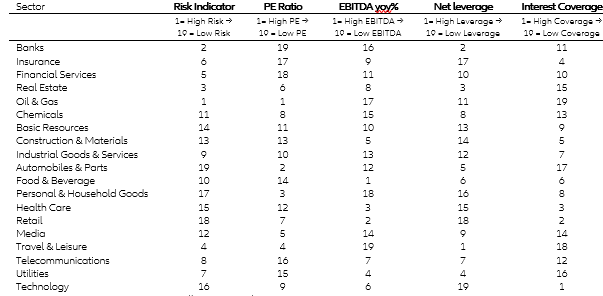

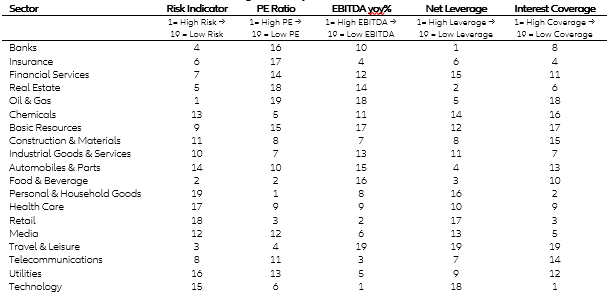

Traded companies have seen remarkable investment inflows even as prolonged Covid-19 lockdowns threaten corporate earnings and debt sustainability. These inflows have led to a substantial re-compression of corporate spreads, leaving most sectors trading close to January 2020 levels. Right after the initial March market sell-off, and aided by central bank actions, market participants rapidly shifted freshly cashed-out funds into both investment grade and high-yield corporate credit (Figure 1 & 2). As of today, the inflow into high-yielding debt has slowed down, while the investment grade universe is still the preferred asset class (mainly due to central bank support). However, the central banks support is not set to last forever as some Treasury secretaries (U.S.) are already claiming back funds dedicated to corporate credit purchases posing an imminent risk to corporate credit markets.

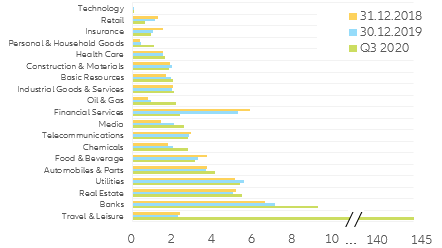

Figure 1: U.S. investment grade long-term fund flows

Figure 1: U.S. investment grade long-term fund flows