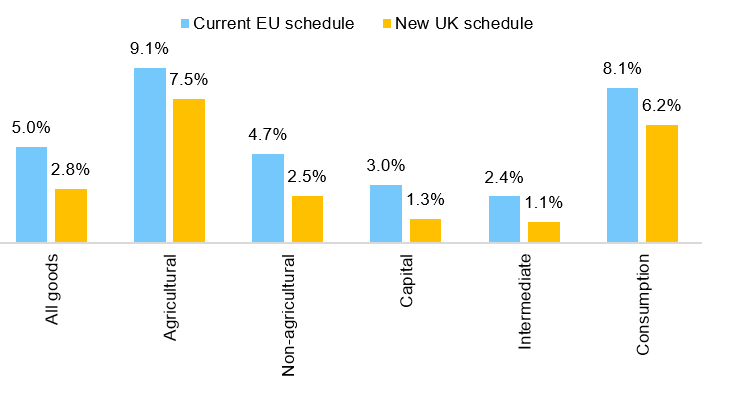

As for Brexit, we continue to expect that the UK will have an FTA with the EU by end-2021, and successful negotiations with third-party countries. Given the Covid19-related delay in the current negotiations with the EU, our baseline scenario (80% probability) is an extension of the transition period to the end of 2021, delaying the implementation of these tariffs by one year. We expect the UK to sign a comprehensive FTA with the EU whereby almost all goods would be duty-free. Moreover,

the UK has secured 20 FTAs (9% of UK imports) that will be implemented at the same time as the EU exit, while 19 are still under negotiation (7% of

UK imports). We take the assumption that

the UK will be able to secure most of these FTAs on 1 January 2022. The U.S. and China are not part of the FTAs under negotiation. As a result, we estimate that in our “Soft Brexit” scenario, 34% of imported goods will be taxed under the new trade policy at the WTO . Also note that non-tariff barriers (administrative and logistics) between

the UK and the EU would significantly increase, even under the most favorable of both scenarios. They are estimated at 10% ad-valorem post Brexit – but cannot be explicitly taken into account in our calculation hereafter. We assume that the exit from the EU, with an FTA, will further push down the GBP by -3% against the EUR, given the rise in non-tariff barriers, the end of passporting rights for financial services and reduced foreign investments in the UK similarly to the post-2017 period.

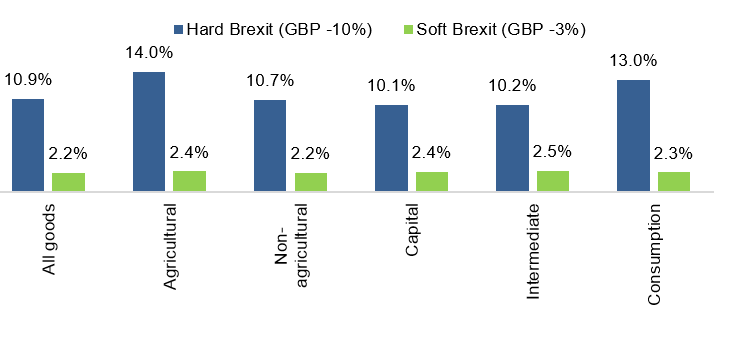

According to our calculations, the aggressive trade policy pursued by the UK could lead to a +2.2% increase in import prices over a year, and be negative for competitiveness abroad. Research has proved that price competitiveness is decisive for

the U.S., while non-price competitiveness is more important for China and Spain. For

the UK and

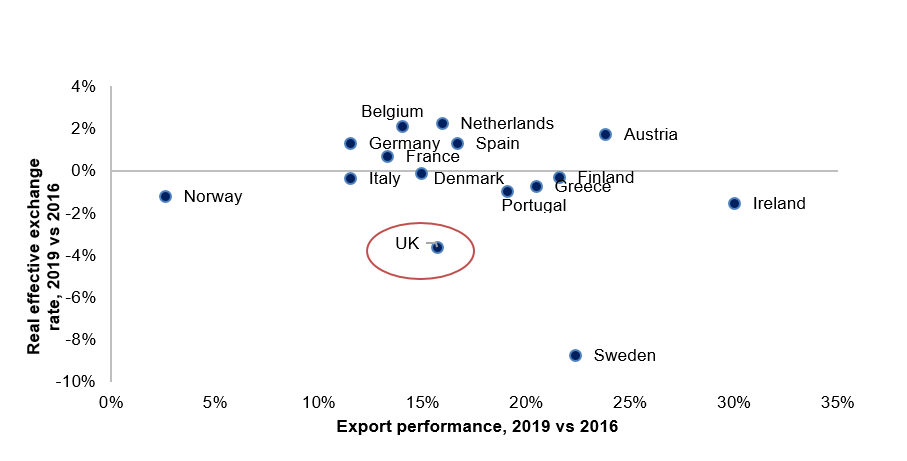

France, for example, both price and non-price effects offset each other . Our analysis looks at the short-term effects of the mix between the currency depreciation and the reduction of trade barriers. It does not include further medium-run currency correction. In case of a Hard Brexit, import prices would increase by +10.9% (see Figure 3). Though a lower GBP should in theory boost export volumes, this J-curve effect may not work for

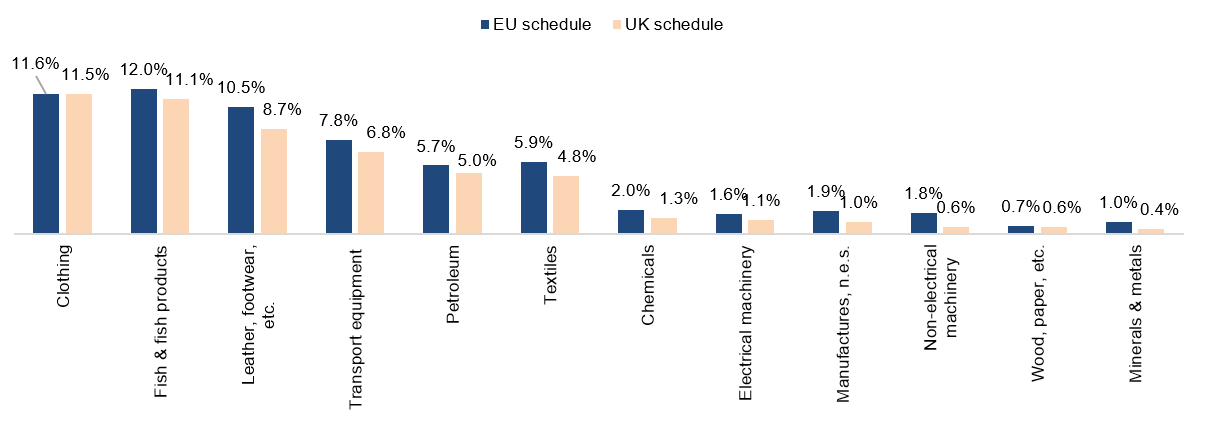

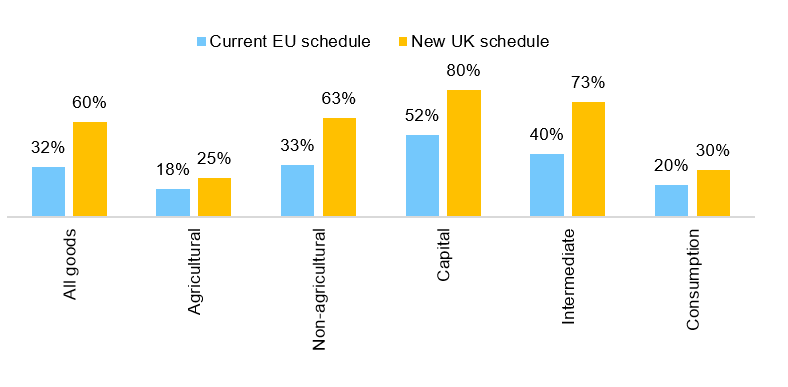

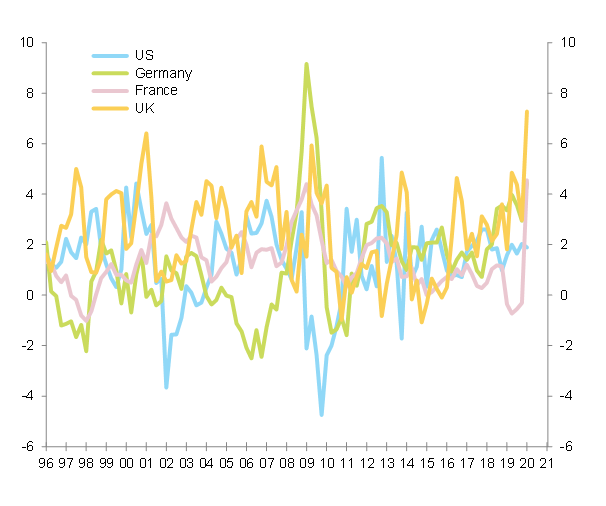

the UK because of its unique economic model. In recent years, though the GBP has lost -3.6% of its value in real terms, exports rose by +15%, while the Euro appreciated and exports from Austria, Spain and the Netherlands increased by +24%, +17% and +16%, respectively (see Figure 4). Capital goods represent more than 16% of total UK imports. While 52% of capital goods imported from MFN countries are duty-free under the current schedule, this share could jump almost +30pp to 80% under the new tariff schedule (see Figure 5). In a Soft Brexit scenario, capital goods import prices would increase by +2.4% (v. +10.1% in a Hard Brexit).

For imported consumption goods, prices are expected to rise by +2.3%, resulting in a +0.7pp increase in inflation, given an average of 30% import intensity in consumption. Consumption goods represent 21% of UK imports. Looking at the consumer basket of goods and services in

the UK, we can see that goods with a high import intensity associated to them (above 30%) will have their trade-weighted average MFN-tariff drop by close to -2pp. In contrast, those with a low import intensity (below 30%) will see their trade-weighted average MFN-tariff drop by only -1.2pp. Under a Hard Brexit hypothesis, imported consumption goods prices would surge by +13.0%, and inflation would jump by a daunting +4pp.

Figure 3 – Changes in import prices under both Brexit scenarios (Hard v. Soft)