EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In 2022, the record bear run across asset classes has eliminated any diversification benefits, leaving investors with no place to hide. Realized and expected monetary policy moves drove most of fixed income and equity performance. In 2023, fixed income should regain some attractiveness from a risk-adjusted perspective and may prove interesting in the current volatile environment. However, the next three to six months, the high macroeconomic uncertainty will continue to expose tactical investors to elevated short-term market volatility and possible short-term losses.

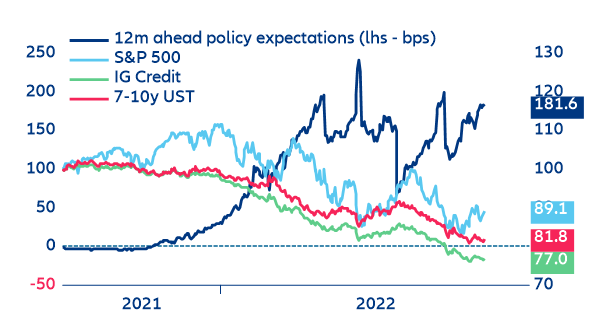

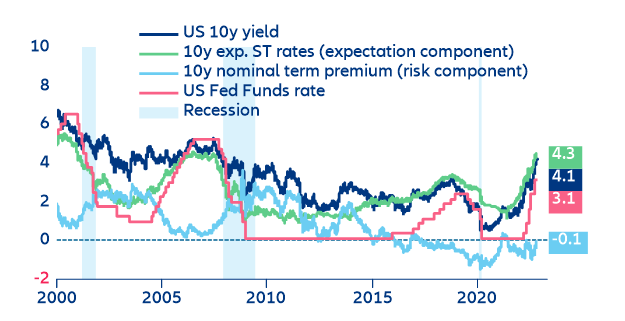

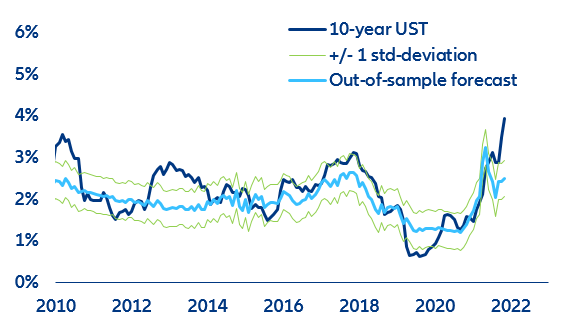

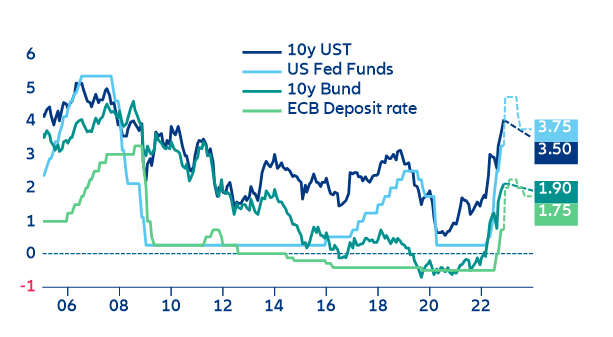

- Monetary policy expectations are driving most of the sovereign yield curve. The historically timid but meaningful policy pivot penciled in our scenarios for H2 2023 should exert downside pressures on both ends of the sovereign curve, leading towards a “price positive” market readjustment. The risk component (the component more attached to fundamentals and mid- to long-term economic expectations) is having a close to negligible effect. In the second half of 2023, long-term yields should start falling towards our targeted 3.5% and 1.9% for the 10y UST and 10y Bund, respectively. Beyond 2023, yields should start stabilizing and fundamentals (the so-called risk component) should once again kick in, with yields slowly increasing towards 4-5% for the 10y UST and 2-3% for the 10y Bund in the mid- to long-run.

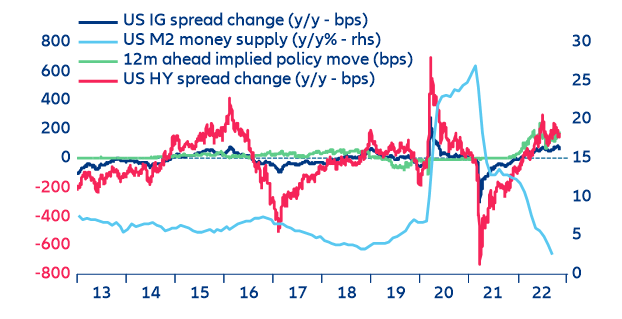

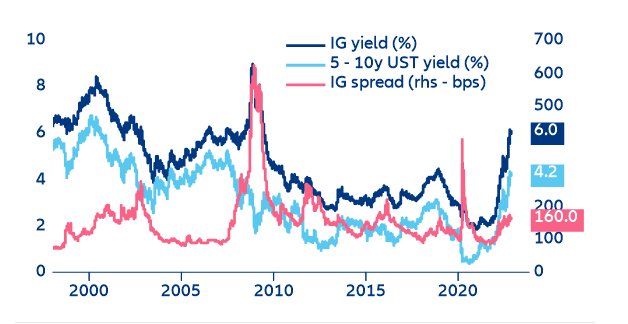

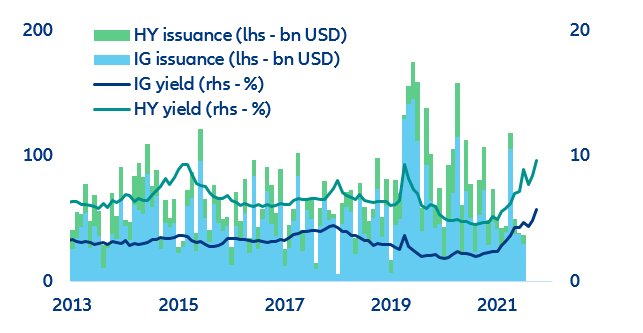

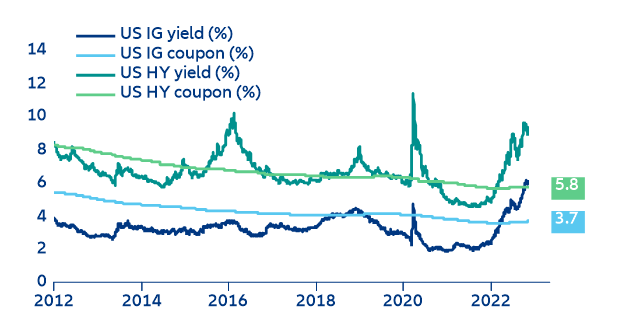

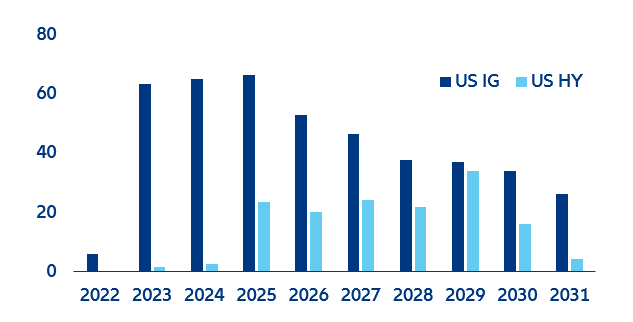

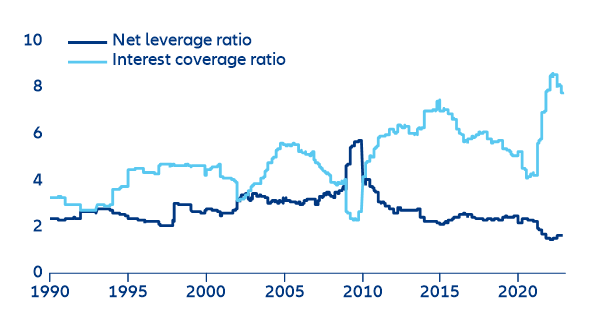

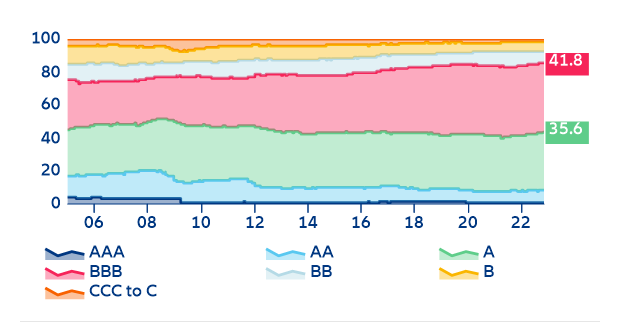

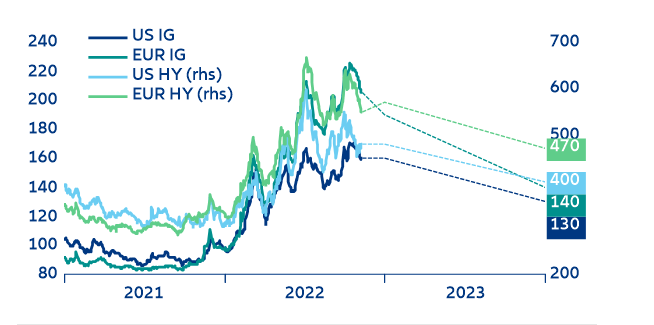

- The current widening of corporate credit spreads has remained moderately muted — and to a certain extent inconsistent with the equity-market meltdown. Moving forward, we remain constructive on corporate credit, warranting a quality bias. The current price performance of corporate credit can be mostly attributed to the global pick-up in sovereign yields and implicitly to monetary policy changes. At the same time, the overall increase in corporate credit yields and subsequent increase in financing costs has led to a slowdown in primary markets, with corporates refraining from raising cash. This situation, however, should not pose a big risk for corporates moving forward as the bulk of financing needs will kick in only in 2024-2025. It would take around three to four years for broad credit markets to experience a notable increase in interest expenses, allowing quite some time for financial conditions to readjust. At the same time, decent fundamentals and overpriced fallen angels probabilities tend to further skew the range of possible outcomes positively. Numerically, we expect further compression in 2023, with both US and Eurozone investment grade spreads landing at levels close to 130-140bps. For high yield, after some pressure until Q1 2023, we expect spreads to compress towards 400-460bps in 2023.

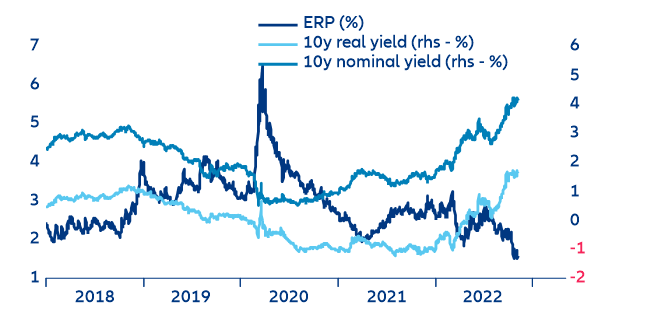

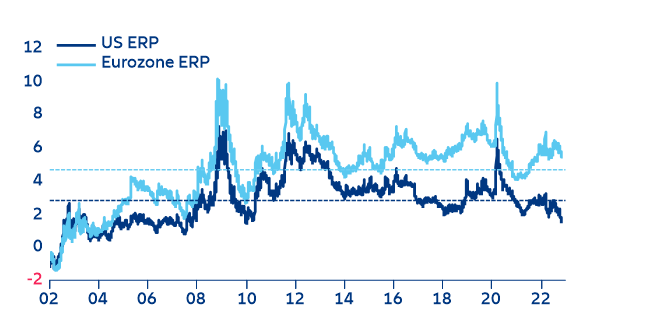

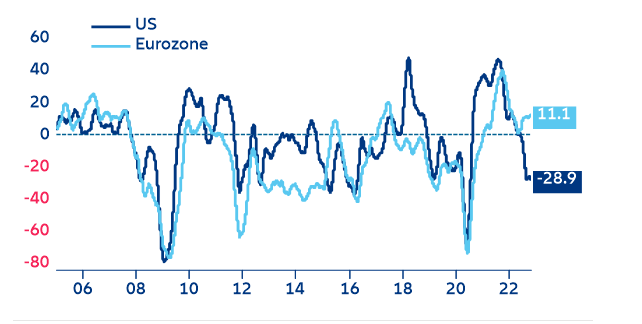

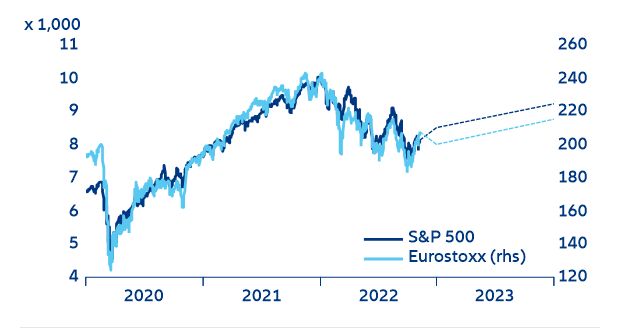

- Short-term risks in equities still outpace the upward potential vis-a-vis fixed income. The coincident behavior between equity valuations and the long end of the sovereign curve has triggered a sharp readjustment in fundamental valuations, correcting some accumulated long-term market imbalances, which may still prove insufficient to warrant a long repositioning. We forecast US and EUR equity markets to lock in an overall -15% correction in 2022. Nonetheless, in H2 2023, equity markets should regain some terrain on the back of abating inflation, renewed economic momentum and the expected policy pivot which should, in turn, lead to an upper-single-digit performance in 2023 and allow for some potential pick up vis-a-vis fixed income. However, and until H2 2023, equity markets do not really look as attractive as fixed income since their current vulnerability to changes in market sentiment make them extremely volatile.

2022, the year that diversification takes a break

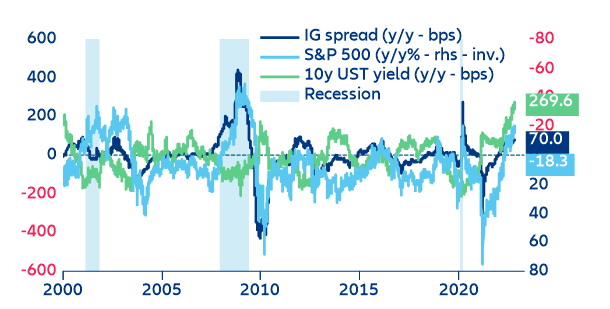

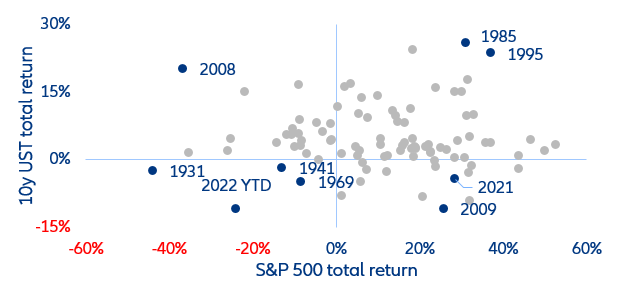

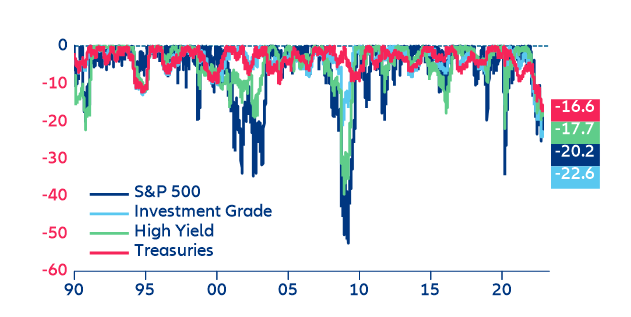

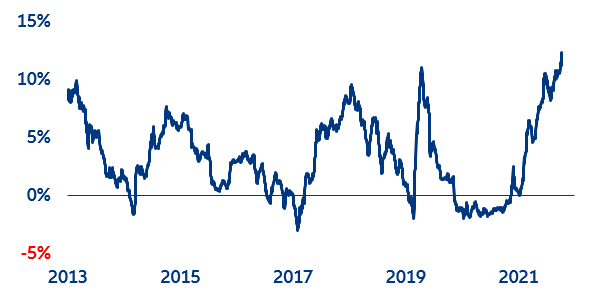

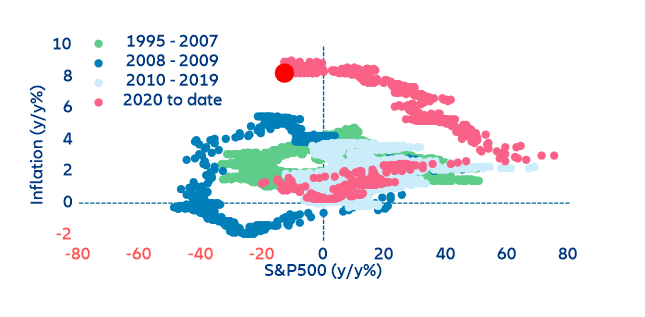

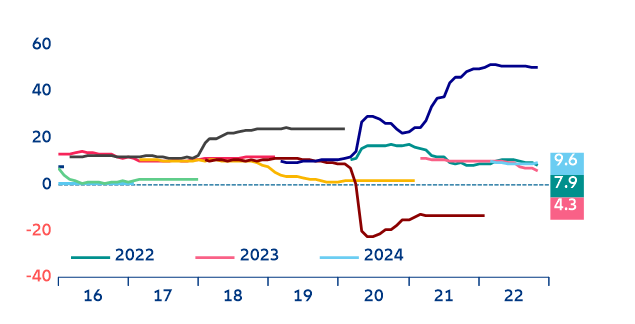

So far in 2022, the record bear run across asset classes has eliminated any diversification benefits, leaving investors with no place to hide. Since the beginning of 2022, market participants have faced an extreme and record-making market bear run, especially for fixed income. What makes this bear run unique is that there has been no place to hide as correlations across asset classes have broadly converged to one, effectively killing any ex-ante expected diversification benefits. While this is not the first time, we see this type of market behavior (which also occurred briefly during the 2013 “taper tantrum” and the pre-quantitative-easing Covid-19 phase), it is extremely rare that such market dislocations have lasted for more than a year. And they show no signs of easing as long as inflation fails to abate (Figure 1). The last time fixed income and equity performed so badly in unison for an extended period and across most regions was in 2008 (Figure 2)

Figure 1: US fixed income vs equities performance comparison (y/y in % and bps)