EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

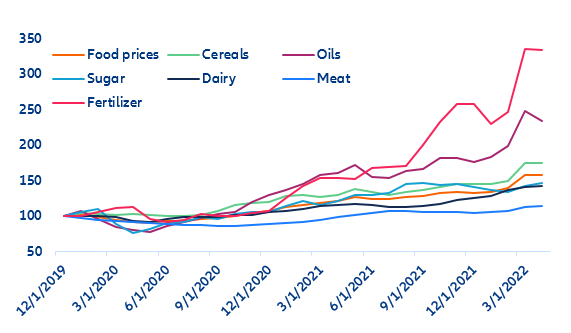

- The war in Ukraine has affected food availability as the country supplied 12% of the world’s grains. While there is still enough to feed the planet, ensuring access is key to avoid a global food crisis, especially as shortages of grain and fertilizer, alongside climate change and lingering pandemic-driven supply-chain issues, have pushed up global food prices by +56% compared to end-2019.

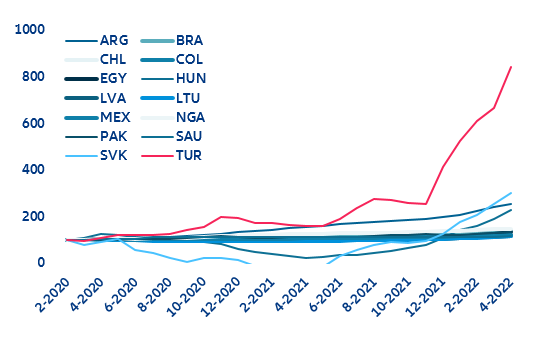

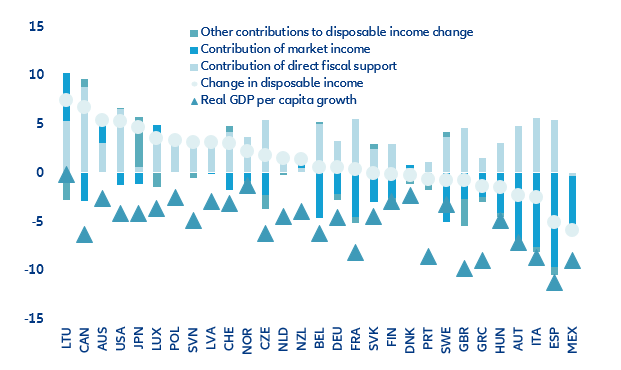

- Disposable income and purchasing power will suffer from the higher inflation environment. The most affected countries in terms of purchasing power are those that have a higher share of food consumption as a percentage of total consumption. Based on the current food price trend for this year (food Consumer Price Index: +425% y/y and 25% of total consumption on food), Turkey could lose over 100% of purchasing power and Lebanon 75% (food CPI: over 300%, 20% of total consumption on food). Similarly, Argentina would lose 15%, given its food CPI at +62% and food consumption at 23% of total consumption. Using a simple panel data approach, we find that, on average, a 1pp increase in the CPI would result in a -0.81pp decline in real disposable income in the absence of government intervention or consumer behavior changes.

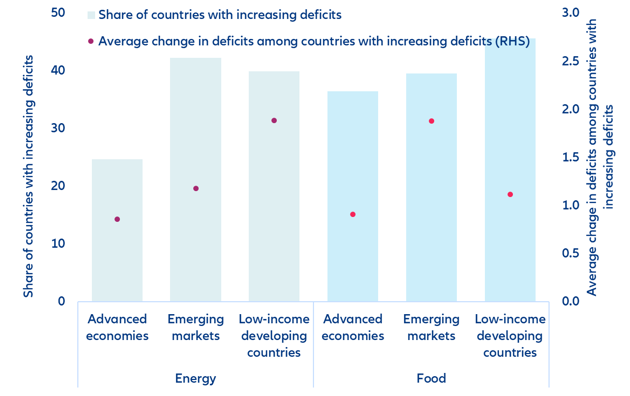

- Countries that have higher import needs and less fiscal space will need to find the right policy mix to maintain financial stability, both in the private and public sectors. Policymakers have already announced measures to counteract inflation, including cutting taxes, cash transfers, subsidies and even price controls. However, many of these actions can carry large fiscal costs and unintendedly increase global imbalances in supply and demand.

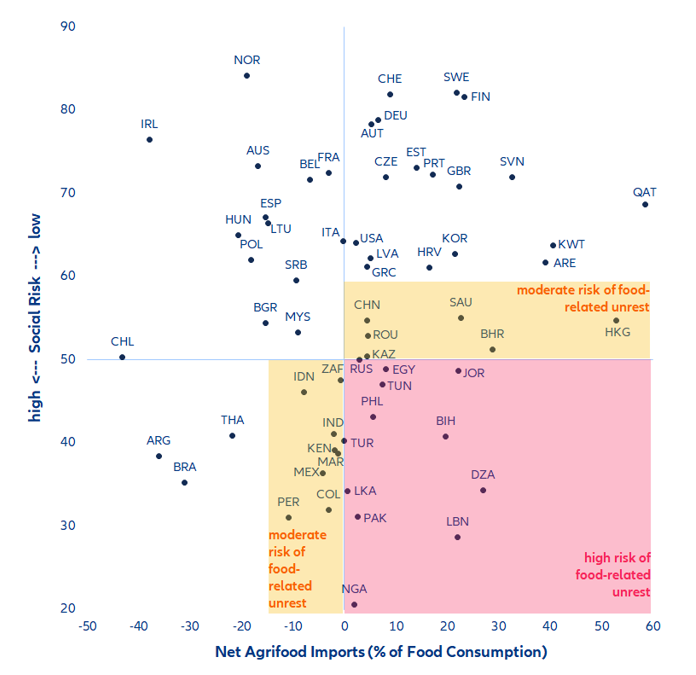

- Net food-importing countries with a high level of social risk are the most vulnerable to social unrest in the current global environment. We identify 11 larger emerging markets that face a high risk of food-related protests in the next few years: Algeria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Tunisia and Turkey. Out of these 11 countries, only Bosnia and Herzegovina and Egypt have so far embarked on consumer-oriented policies to mitigate the food price shock for households.

Arab Spring? Summer? Fall? Winter?

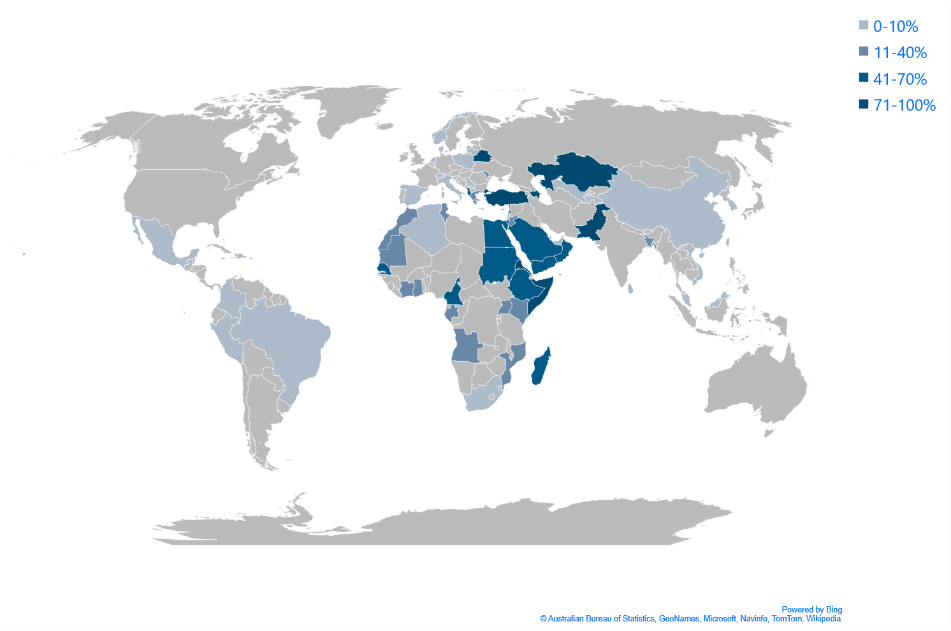

The war in Ukraine has created the perfect storm for a global food crisis that could last for years. Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the latter supplied 4.5mn tons of agricultural produce through its ports – 12% of the world’s wheat, 15% of globally traded corn and 50% of the planet’s sunflower oil. Russia and Ukraine cumulatively supplied 28% of traded wheat. Now, without access to these markets, the coming years could see a resurgence of malnutrition and mass hunger (UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ in the Global Food Security Call to Action), with millions of people at risk of food insecurity.

Figure 1: Percentage of wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine