- In 2020, Working Capital Requirements in the West increased (+5 days in North America and +1 day across Western Europe) while it dropped in regions such as Latin America (-3 days), Eastern Europe (-2 days) and APAC (-1 day). Inventory management and government support explain most of this divide. In the US and EU, severe lockdowns pushed companies into a "forced" stockpiling mode, which was fortunately tempered by the “invisible bank”, i.e. the very accommodating management of payment terms between customers and suppliers, , partly financed by liquidity support measures. 2020 saw a surge in WCR across industrial sectors: +13 days for metals to 95 days, +9 days to 117 days for machinery, +4 days to 84 days for paper and +3 days to 87 days for automotive.

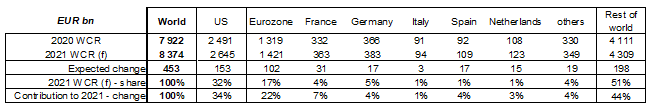

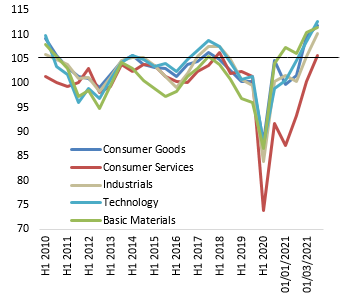

- Looking ahead, we estimate that large companies will face a record increase of EUR453bn in WCR in 2021, equivalent to +4 days of turnover, up to EUR8.4trn. This comes in a context of the strong demand rebound triggered by the grand reopening, alongside severe shortages in inputs, labor and final goods. The surge in WCR already observed in most developed economies will ramp up in 2021, while WCR would remain well under control in a few emerging countries, notably in China (-6 days). In both the US and the Eurozone, we expect WCR to rise by +4 days.

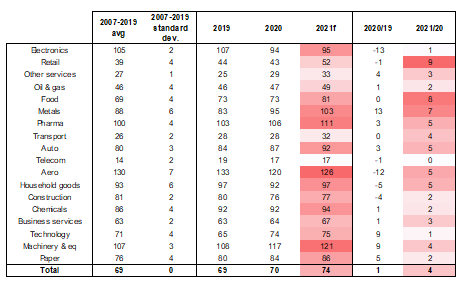

- While all sectors will see a rise in WCR, consumer goods sectors could see the biggest jump. Last year was a year of divergence. We expect many global sector WCR levels to resynchronize on the upside in 2021, with retail (+9 days up to 52 days) and agrifood (+8 days up to 81 days) seeing the largest rises, followed by industrial sectors such as metals (+7 days up to 103 days), transport equipment (+5 days) and machinery (+4 days).

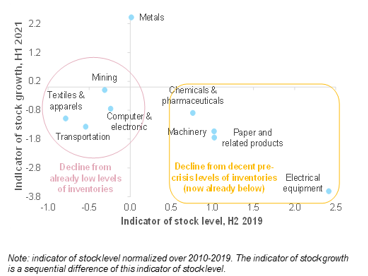

- Stocks matter: Along with the “just in case” model of inventory management, and the end of “just in time” for most sectors, rebuilding stocks in an environment of supply shortages will be the key driver of the increase in global WCR, notably across Western European countries. In 2020, Days Inventory Outstanding surged by +5 days in North America and by +1 day in Western countries, while the drop in inventories across Emerging Markets made up for the stockpiling in developed economies. In 2021, we expect pent-up demand and the massive restocking policies of Western companies in the midst of global supply-chain disruptions to weigh notably on their WCR levels. However, in 2022, reduced supply bottlenecks should mitigate the soaring inventory fallout on developed countries' WCR.

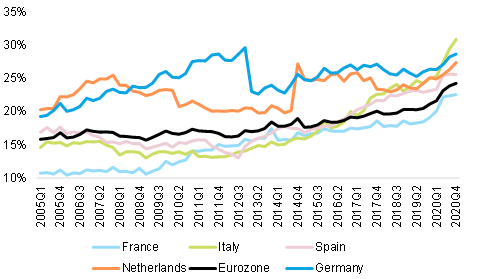

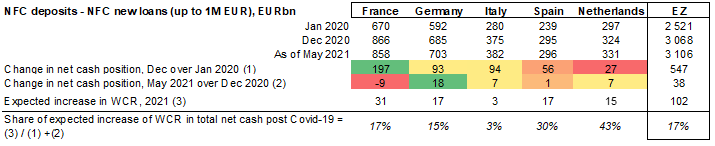

- State support matters, too: The additional WCR needs represent less than 20% of non-financial corporates’ net cash positions in the Eurozone. However, total deposits of non-financial corporates cover at best 30% of total debt, with France the most vulnerable. Our estimations for the Eurozone show that NFCs’ net cash positions (deposits – new loans up to EUR1mn) increased by EUR547bn in 2020, almost three times more compared to 2019. This compares to EUR102bn of expected additional WCR needed to be financed in 2021, i.e. 17% of 2020 net cash positions. Since the end of 2020, net cash positions have continued to increase in the Eurozone (EUR38bn as of May 2021), with Germany (+EUR18bn) and Italy (+EUR7bn) on top of the list, while in France net cash positions fell by -EUR9bn. However, if the grace periods on state-guaranteed loans are not extended beyond 2021, cash buffers will decrease as total deposits on non-financial corporates cover 30% of total debts at best, with only 23% in France, one of the lowest ratios.

“Forced” stockpiling financed by the “invisible bank” – and government support

In EMs, total inventory levels were minimally impacted as demand for goods picked up and has remained strong since the summer of 2020. In contrast, the more severe lockdowns in the US and EU pushed companies into a “forced” stockpiling mode. France, Denmark and Spain, for example, saw their inventory outstanding level surge by +5 days, +7 days and +10 days, respectively, last year. The very accommodating management of payment terms between customers and suppliers fortunately tempered these increases in inventories in some Eurozone countries. France, for example, succeeded in seeing its WCR drop by -2 days over the year, thanks to longer payment terms to suppliers (+6 days) in relation to shorter payments from customers (-1 day).

Massive stockpiling always weighs on WCR levels and cash balances accordingly. However, it is not always a bad thing: it can pay off if it arises from companies’ expectations about future demand growth, to be sure of being able to cater to clients’ orders on time after the crisis period. Conversely, if stockpiling results from an inability to deplete current inventories fast enough, it usually brings on cash shortages for the company, which could end up going bust in the worst case. The different levels of change in WCR from one sector to the other also depend on where they are located in the global supply chain scale in regards to the final consumer. The more a sector is capital-intensive, the more it undergoes a significant WCR rise as any supply disruptions are more expensive when a plant has to temporarily stop production due to a lack of inputs.

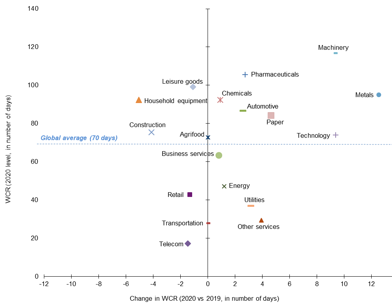

2020 saw a surge in WCR across industrial sectors (see Figure 1): +13 days for metals to 95 days, +9 days to 117 days for machinery, +4 days to 84 days for paper and +3 days to 87 days for automotive. These sectors were forced into stockpiling during lockdowns instead of shutting down their plants because of how high closure costs usually are for capital-intensive activities. Overall, metals and machinery were the two losers in regards to last year’s changes in WCR: The Covid-19 crisis has highlighted how inflexible their manufacturing tools are in case of a sudden change in the economic cycle, especially from the inventory point of view. Conversely, the sectors most exposed to the boom of remote work saw their WCR level massively benefit from resilient demand and destocking. This includes electronics ranging from semiconductors to computers (-13 days down to 94 days) as the sector saw skyrocketing demand in 2020. Household equipment saw a fall in WCR of -5 days (down to 92 days), thanks to better-than-expected sales during lockdowns while construction also registered a fall in WCR (-4 days down to 76 days) as the sector cashed in on the shutdowns of new building programs to sell off all inventories left.

The two special cases are pharmaceuticals and automotive, which both saw their respective WCR rise by +3 days, pushing them up to a ten-year record high: 106 days of turnover for the former and 87 days of turnover for the latter. In spite of selling its medicines through drug stores, the pharmaceuticals sector unfortunately bears a very high level of WCR because drug makers usually deal with public hospitals and social security programs with very long payment terms. Conversely, pharmaceuticals has always generated a high level of cash flow so that it can easily support longer payment terms. The high WCR in the automotive sector has more to do with car dealers closely linked to carmakers by the fact that they share the same brand and usually support the funding of the largest part of car inventories.

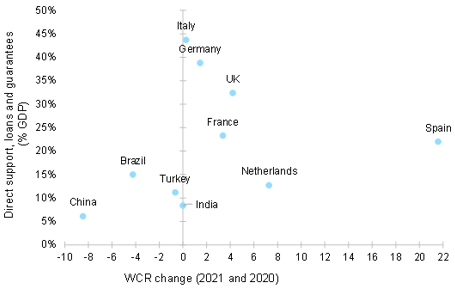

WCR, just like Days Sales Outstanding (DSOs), tend to increase both in recession and recovery times. In Figure 2, we try to graph the effect that unprecedented liquidity support measures by governments have had – and continue to have – on compressing WCR variations. Initially designed to avoid hysteresis effects (bankruptcies and unemployment), and unlike the 2008-09 crisis, the Covid-19 crisis response has been very much focused on avoiding liquidity gaps and preserving B2B flows and credit. Using IMF data on liquidity support measures (state-guaranteed loans, moratoria on debt, subsidies) and our own WCR calculations (2021 forecasts explained hereafter), we see the lifeline from governments to help suppliers (the invisible bank) continue to finance their clients. In Europe, for instance, the WCR change has been quite limited, alongside very generous liquidity bridges. Also note that initial conditions (WCR levels, structure of the economy), as well as varying intensities of the crisis or recovery, certainly explain specific country developments (Spain and China for e.g.) In large Emerging Markets, we see that liquidity gaps may have been only partially bridged and that corporates will be faced with binding financing constraints as they return to pre-crisis activity.

Figure 1: Global sector WCR in 2020, in number of days (worldwide average)

One of the strongest increases of global WCR on record

Figure 3: Breakdown and 2021 forecasts of WCR amounts (EUR bn)

Similarly, when looking at sectors, the rise of WCR is likely to affect all 18 that we monitor, in line with the return to growth prompted by the grand reopening and massive vaccination campaigns, which will improve demand prospects. Hence, we expect WCR to resynchronize on the upside in 2021 at a global level, with the largest increases seen in sectors linked to final consumer goods or closely related to them. Yet, sectors considered as strongly industrial should also see their WCR rise in 2021, such as metals, pharmaceuticals, transport equipment and machinery due to surging commodity prices, which will raise their production costs.

Figure 4: Inventories by sector

Which sectors are the ones to watch? Agrifood (+8 days up to 81 days), retail (+9 days up to 52 days), transport (+ 4 days up to 32 days) and household equipment (+5 days to 97 days). We also expect large rises in WCR for metals (+7 days up to 103 days), pharmaceuticals (+5 days), transport equipment (+5 days) and machinery (+4 days). Last year, the transport equipment (aeronautics) sector benefited from the large destocking of Boeing's 737 Max planes since these were allowed to fly again from the last quarter of 2020.

The WCR levels for electronics (+1 day), energy O&G (+2 days) and telecom (+0 days) are expected to remain around their long-term historical levels. Their WCR are better suited to withstand any upward pressures despite the acceleration of the recovery around the world. Now more than ever they have become instrumental to the new industrial background taking shape through global digitalization, which puts them in a strong position to set payment terms for both customers and suppliers.

Our WCR forecasts highlight a ten-year high level in 2021 for some sectors, notably agrifood (at 81 days), retail (52 days), pharmaceuticals (111 days), automotive (92 days) and machinery (121 days). These record levels could put companies at risk if they are denied additional credit lines from banks when they need to finance their operating cycle on a rise.

Furthermore, agrifood and retail are two specific sectors strongly destabilized by the booming remote work and e-commerce models, respectively. Not only has e-commerce prevailed over brick-and-mortar retail throughout the world, but also it is faster than before the Covid-19 crisis. Yet, meeting customers’ demands online usually requires e-commerce players to bear a higher level of stocks than retail outlets. It is all the more required now that consumption patterns have shifted towards durable goods, and government income support strengthened demand, while transportation services were limited. The conjunction of booming demand for consumer durables from Asia and supply-side bottlenecks created by sanitary restrictions in ports and terminals have kept shipping costs elevated for several months and made it all the more important to keep high inventories in the West.

However, stockpiling can also result from an inability to deplete current inventories fast enough. As a result, it can usually bring on cash shortages that could even push a company to go bust in the worst case. If replenishing current inventories, particularly in the northern hemisphere, is fueling the rise in WCR globally, changes in payment terms granted to clients should add to this upswing over 2021. This is because a relaxation in payment terms is usually an easy way of getting back market shares that could have been definitively lost by the supply disruptions that occurred last year due to the pandemic.

State support to play the role of the “invisible bank” in 2021?

In the Eurozone, companies’ available cash surpluses generated by massive state support policies (notably direct liquidity support and state-guaranteed loans) appear to be significantly higher than the looming additional amounts of WCR.

Our estimations for the Eurozone show that the net cash positions (deposits – new loans up to EUR1mn) of non-financial corporates increased by EUR547bn in 2020, almost three times more compared to 2019. This compares to EUR102bn of expected additional WCR needed to be financed in 2021, i.e. 17% of the 2020 net cash positions. Since the end of 2020, net cash positions have continued to increase in the Eurozone (EUR38bn as of May 2021), with Germany (+EUR18bn) and Italy (+EUR7bn), on top of the list, while in France net cash positions fell by –EUR9bn, which suggests non-financial corporates have started to use their deposits in addition to new loans for operating activities (see Figure 6). German companies benefit from half of the French amount of cash surpluses stemming from public support policies back in 2020 (EUR93bn against EUR197bn in France). The positive point is that the first five months of 2021 show a further rise in cash generation of EUR18bn, which will fully cover the additional WCR expected in 2021. This stems from either additional public support programs or German companies’ profitability generating positive cash flows again since the beginning of the year alongside recovering export flows.

Figure 7: Available cash positions in 2020 and additional amount of WCR to be funded in 2021

Figure 8: Share of coverage of total stock of loans & debt securities by total non-financial corporates’ deposits