The rise in uncertainty could cut UK GDP growth by as much as -0.1pp per quarter over the next two quarters while pushing companies to strengthen their contingency stocking in an environment of low domestic demand. Thus, rising uncertainty triggered a downward revision of our GDP growth forecast by -0.1pp in 2018 and 2019 to 1.3% and 1.2% respectively.

The more the uncertainty shock persists, the more it damages the economy, as it can result in negative wealth effects through tighter financial condi-tions, a weaker consumer, and fragile company profitability.

(1) Negative wealth effects would be accentuated by the slowdown of activity in the construction sector, which could register a more rapid adjustment should uncertainty rise. Already, price growth has been cut in half since the Brexit vote.

(2) Over 2016 and 2017, consumers lost -0.6pp in purchasing power with a trough in mid-2017. Supporting the actual levels of consumption, albeit weak, would require an adjustment of the saving rate. The latter stands at a historically low level (4.4% in Q2 2018). Hence, we expect consumer spend-ing to continue to slow down: +1.3% in 2018 after +1.8% in 2017 (it stood above 3% prior to 2017) and +1.0% in 2019.

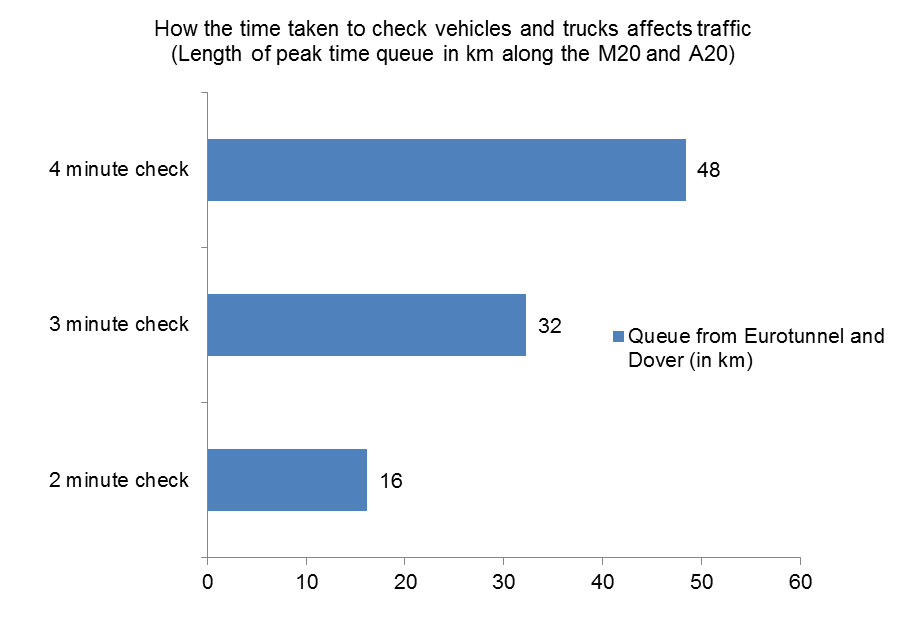

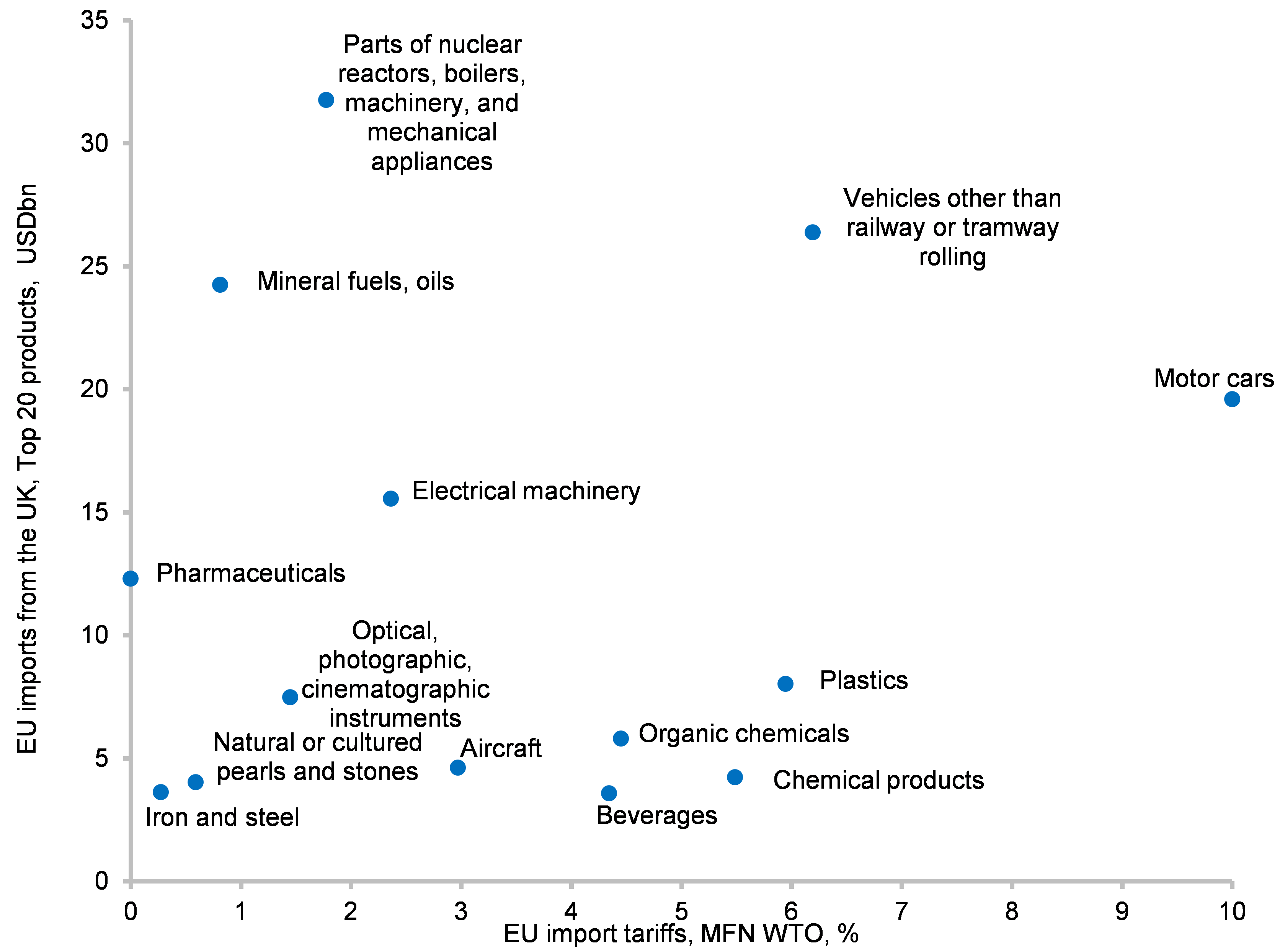

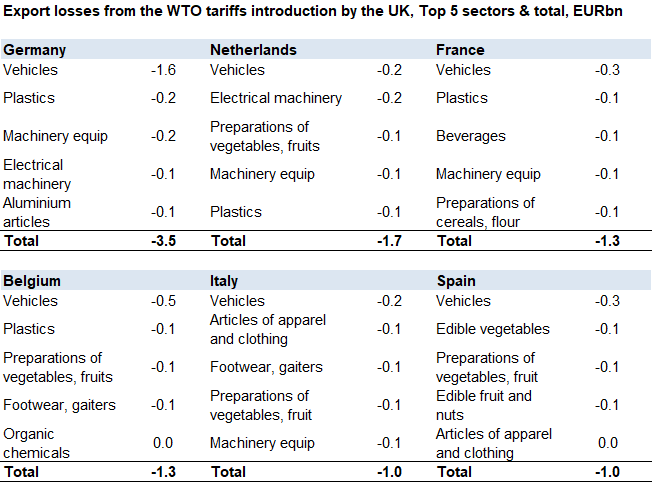

(3) Non-financial corporations’ margins lost -2.5pp since the start of 2016 when the sterling entered its depreciating trend. The fall is expected to con-tinue given the recent wage growth acceleration. Significant labor market shortages should keep wage growth above +3% y/y for the coming months. We believe that some UK companies will increasingly look for domestic sup-pliers in order to protect their margins, notably in those sectors where de-pendency on imports is high: automotive, chemicals, machinery and equipment, retail and agri-food. Some local capacity will be freed-up by the fact that there is an increasing number of EU companies which start to switch from UK to EU suppliers. Some recent examples have confirmed this trend. Fears of custom checks between the UK and the EU or a hard border with Northern Ireland have increased.

Last minute deal: A blind date between the UK and Europe?

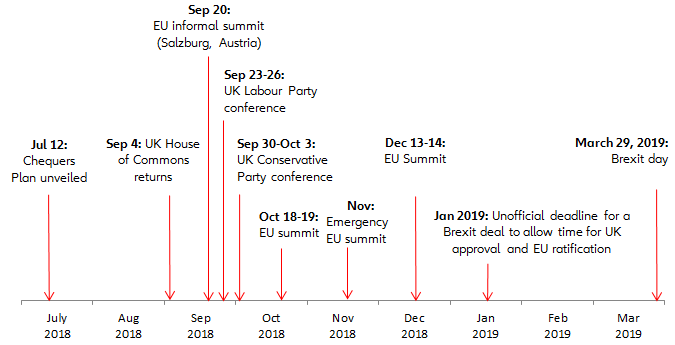

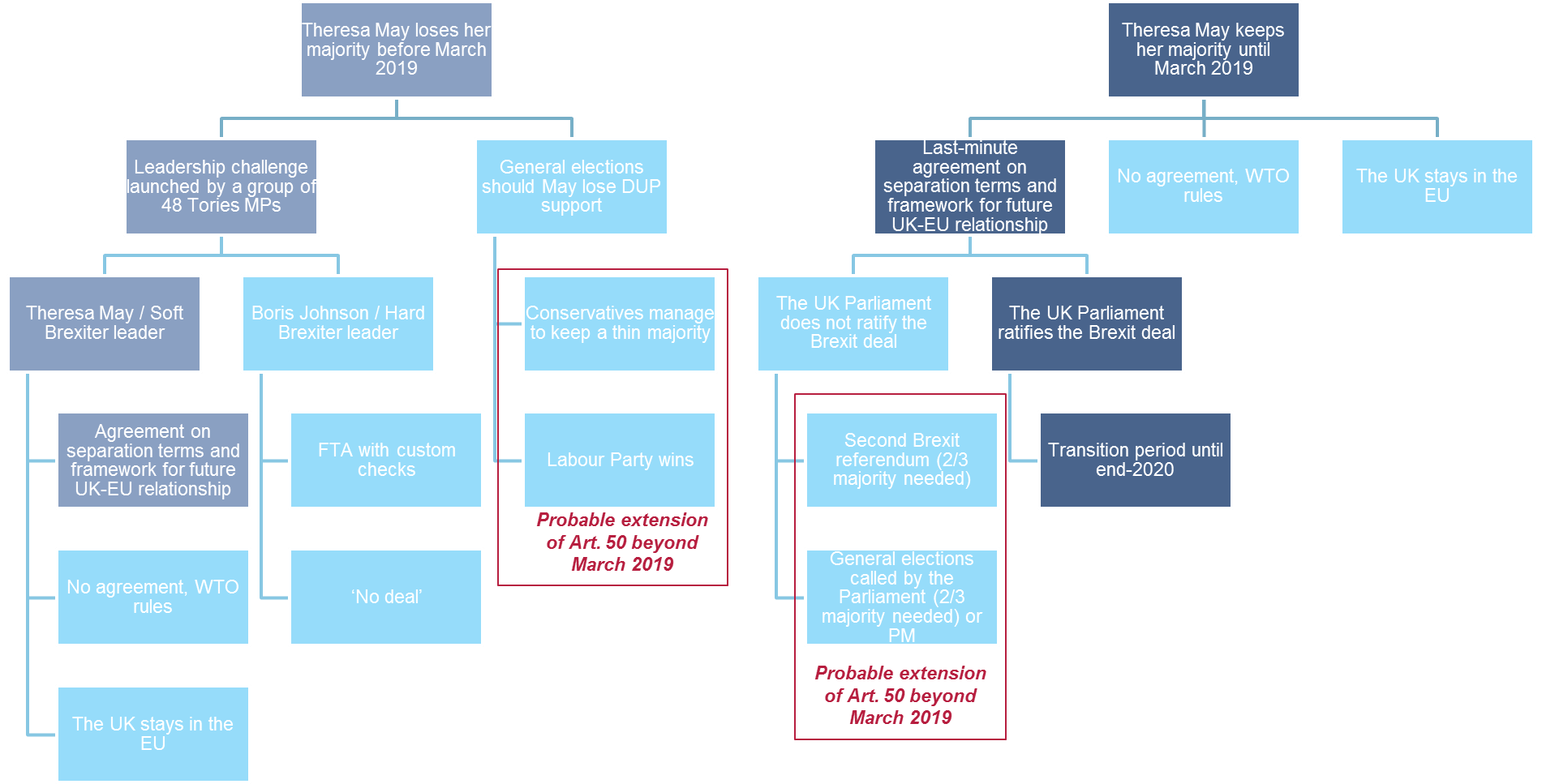

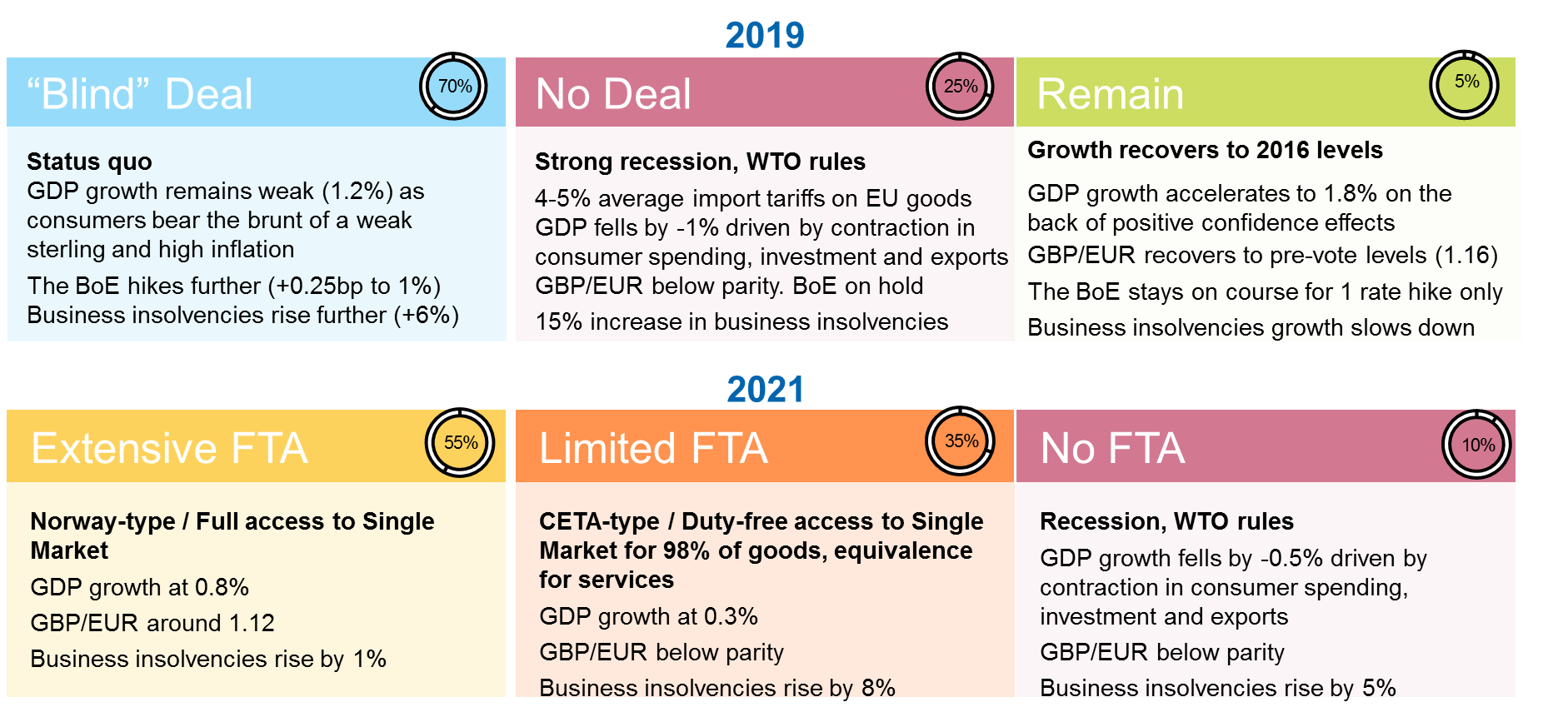

Our central scenario (70% probability) continues to be a last-minute agree-ment by January 2019 which would validate the 21-month transition period. January 2019 is the minimum must-have time to allow ratification by the UK Parliament and the EU (European Council, European Parliament).

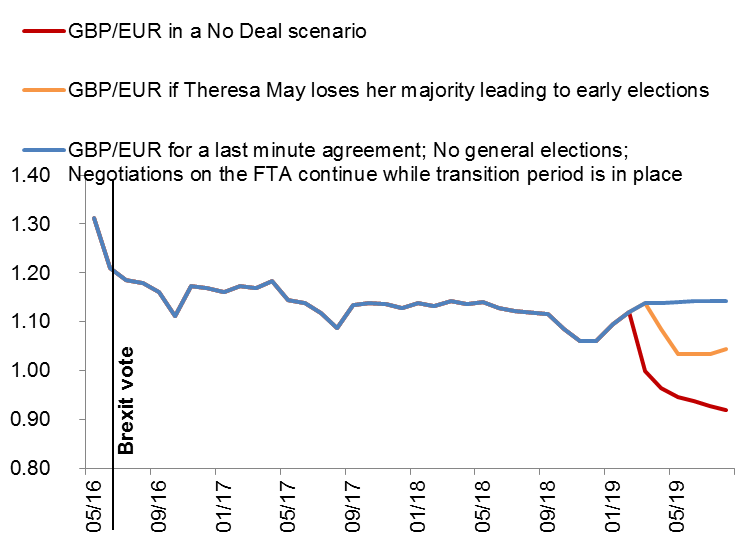

An agreement is likely to give temporary relief to financial markets and no-tably to the sterling. We estimate the sterling to rebound to 1.14 by April 2019. The Bank of England is expected to continue on its path of one rate hike (+25bp) per year, with the next one to come in Q2 2019.

However, the political declaration on the future Trade Relationship with the EU is likely to lack very concrete details and to look more like a “Blind Brexit”. It will most probably state that both sides agreed to work on “a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with very close ties”. While the outlines of an agreement on the future EU-UK relationship may be included along with the divorce deal, a formal trade accord would not be published out until the end of the transition period, deemed to end in December 2020. This would be in the interest of both sides, notably the EU given the uncertainty related to the next EU Parliament composition and the European Commission.

2021: Norway is the way

An ‘Extensive FTA’ similar to Norway in 2021 – our central scenario – would avoid Ireland’s dislocation. It would also allow Conservatives to keep their majority in the Parliament as they depend on the 10 seats from the Demo-cratic Unionist Party from Northern Ireland.

Pros. The Norway-type of agreement would mean that the UK will join the European Economic Area (EEA). This will give the UK full access to the Sin-gle Market for industrial goods, excluding some agricultural and fisheries products, while requiring minimum physical custom checks. The services sector would also have full access to the Single Market which would allow the UK to keep passporting rights instead of requiring equivalence status . In addition, the UK would be able to negotiate bilateral FTAs with third coun-tries.

Cons. The UK would not be able to control EU migration and the EU rules would need to be respected. In addition, the UK would not have any voting rights within the EU institutions or changes in regulation. The UK will need to copy or replicate all the 40 FTAs with around 70 countries that the EU has in place currently. Ten of the UK’s top 50 export markets for goods were cov-ered by EU trade agreements, which represents around 11% of UK trade, while the ones that are currently close to finalization or awaiting ratifica-tion account for another 25% of UK trade.

Figure 4: Summary Brexit scenarios