EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The Covid-19 crisis and, more recently, the war in Ukraine have led to some re-thinking of financial globalization. In particular, large emerging countries are showing growing discontent against the Western USD-centered framework. The rise of the Chinese economy (and its geopolitical assertiveness) seems to make the CNY a natural challenger.

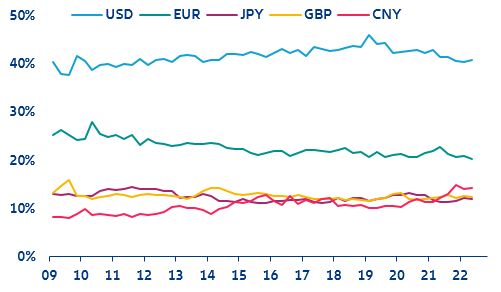

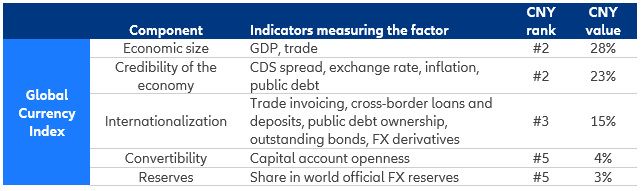

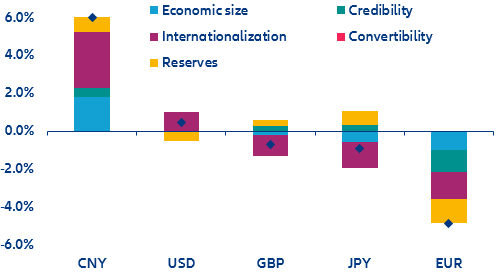

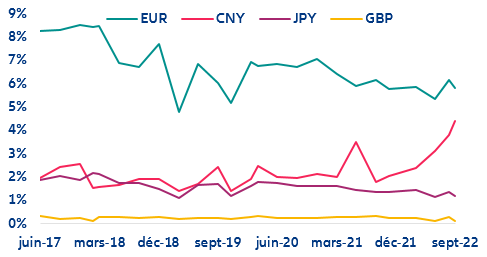

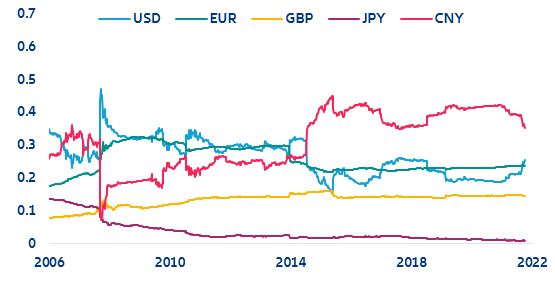

- We find that since 2009, the CNY’s role in the global financial system has nearly doubled, just surpassing the JPY and GBP. Getting on par with the USD is likely to take much longer, if it is even possible at all. Our analysis is based on a cross-country comparison of the economic size of the country issuing the currency, the credibility of the currency as well as its internationalization level, convertibility and reserve currency status.

- The next phase of financial globalization could be a polarized system. The rise of the CNY is not only a topic of financial development and diversification, but also geopolitically charged. In an optimistic scenario, global finance could be heading towards a multipolar system where economic agents use both the USD and CNY seamlessly. In a pessimistic scenario, two spheres of influence could form (US and USD vs. China and CNY), with little exchanges. The reality could lie between these two extremes as going forward geopolitics is likely to guide economic trends much more than in the past.

- However, the path towards a polarized financial system is not straightforward. While progress in China’s reforms towards capital account liberalization had been fast in the 2000s and early 2010s, there have been some roadblocks. Stronger capital controls were put in place in 2015-2016 to contain the strong depreciation of the CNY and some bold Belt and Road Initiative investments did not always prove sustainable. Sweeping regulations in 2021 also raised concerns regarding political risks. While Chinese leaders likely still aim to raise the global role of the CNY, a rising number of issues in China could risk slowing down the pace of further reforms and the opening of the financial system.

- Technological developments as a way to leapfrog? China has plans to combine its widely used central bank digital currency (CBDC) with blockchain technology – once efficiency and reliability gains are proven. This could accelerate the CNY’s role in the global financial system.

The Covid-19 crisis and, more recently, the war in Ukraine have led to some re-thinking of globalization: Supply chains turned out to be more vulnerable than expected and many countries had developed food and energy dependencies that weakened socio-demographic resilience. While trade globalization seems to have plateaued (and seems unlikely to reverse), could the financial globalization centered on the cross-border use of the USD in transactions and trade be challenged? What are the alternatives, and what would it take for them to be viable? Is the coexistence between a challenger currency and the USD possible under the current system, or it would imply a transition to a different one?

Challenging the dominance of a currency: we have seen this before

The rise of the US dollar (USD) as the world’s dominant currency during the last century can provide valuable lessons for what might lie ahead. Until World War I, the British Pound (GBP) was still the major international currency, even though the US economy had already overtaken the British economy in terms of national output by the 1870s. However, it took until 1913, when the creation of a central bank (Federal Reserve) helpedthe US develop a deep, liquid and open financial system that would elevate the status of the US dollar, matching the country’s economic power. During World War I, the US also provided large amounts of loans to the UK (and other countries), further strengthening the international position of the USD. After World War II, the USD remained backed by gold, while the GBP (and other major currencies) were not. Since then, the USD has become the dominant global reserve currency. Now, the rise of the Chinese economy (and its geopolitical assertiveness) seems to make the CNY a natural challenger to the dominant Western USD-centered financial system. China’s rapid rise as a leading trading partner could rival the existing currency regime, much like the USD challenged the status of the GBP. However, as history tells us, economic influence is definitely not the only factor at play. Based on existing academic research, we find that the following five factors help summarize the determinants of the global role of a currency:

- Economic size of the currency’s issuing country

- Credibility and confidence in the currency as a storage of value

- Internationalization of the currency, namely the usage in cross-border trade and financial transactions

- Convertibility of the currency or the level of restrictions on capital flows

- Reserve currency status, i.e. whether if other central banks are holding the currency (as protection against crises)

The USD remains by far the most dominant currency

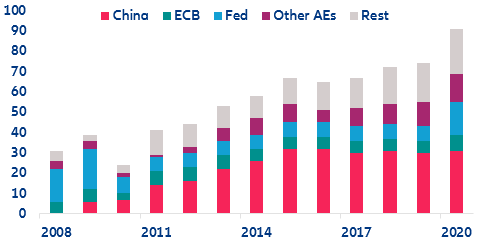

Based on these five concepts, we build a country-specific Global Currency Index for the currencies of the major developed economies, i.e. the USD, EUR, JPY and GBP (sometimes labelled the “Big Four”) as well as the CNY. Each factor is measured by a number of indicators (some of which we detail later in this report) and the final Global Currency Index is a weighted average of the five factor. The Global Currency Index is not an absolute scoring measure of a currency’s global role. This means that there is no ideal or maximum value to be reached, but rather the Index should be read as a relative measure of a currency’s global role compared to others. We find that the USD remains by far the most dominant currency, while the JPY, the GBP and the CNY have been at similar levels in the past years (and the EUR in-between) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Global Currency Index