EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

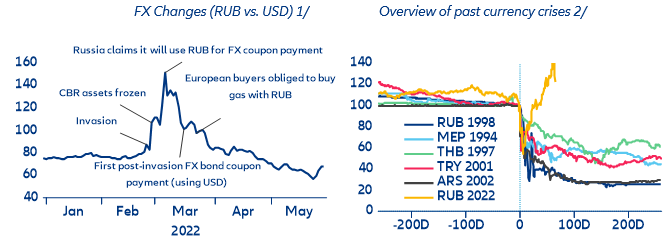

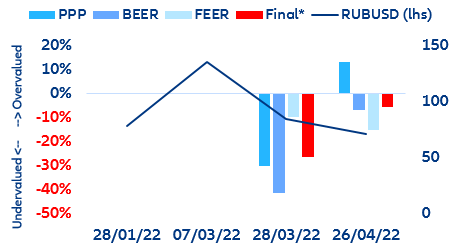

- Against initial expectations, comprehensive sanctions did not plunge Russia into a currency crisis. Unlike other emerging market currencies during times of stress, the Russian ruble experienced a short-lived depreciation. After plummeting in the early days of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, the ruble has staged a remarkable comeback and has more than doubled against the US dollar from its March slump, becoming the best-performing emerging market currency so far this year.

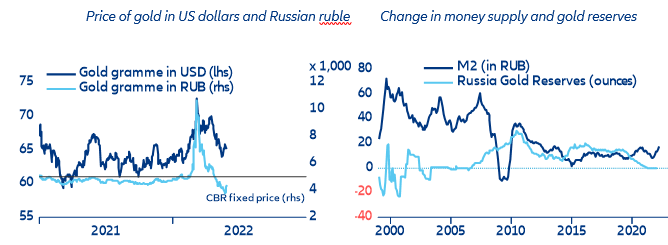

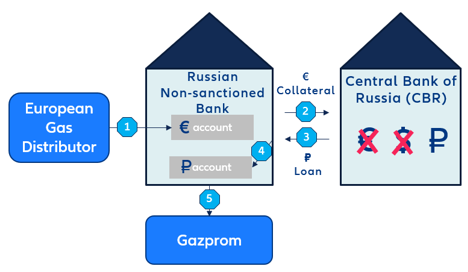

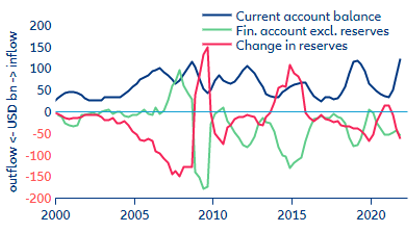

- Several factors explain why Russia averted a currency crisis despite the freeze of most of its central bank reserves. The current account surplus soared to a record USD58bn in the first quarter of 2022, and could climb as high as USD250bn (in the absence of a comprehensive embargo on energy exports and a sanctions-induced compression of imports). The Russian authorities also took timely countermeasures to orchestrate an “FX intervention by delegation,” including stringent capital controls, a temporary gold-fixing of the ruble and asking energy importers to switch payments to rublestogether with a steep policy rate rise to stabilize the ruble after it plummeted.

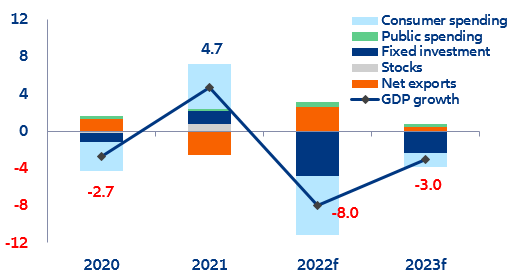

- However, the ruble’s rapid ascent might have reached a turning point and could eventually backfire. Since the ruble trades in a very thin market (and mostly domestically, given the dramatic drop in demand outside Russia due to sanctions), its recent appreciation belies a struggling domestic economy, which is expected to slump into a severe recession this year - but it has real consequences. Since most energy exports remain FX-denominated, a stronger ruble hurts the government’s budget balance by lowering the local currency value, which could be further impacted by the potential for EU tariffs on Russian energy exports during the phase-out of oil imports. Last week, the central bank responded with the third rate cut since April to tame the currency’s appreciation. Going forward, the current upward pressure on the ruble is likely to subside over time as some of the Russian countermeasures expire, Russian energy exports become less competitive and the deteriorating economic outlook begins to weigh on the FX rate.

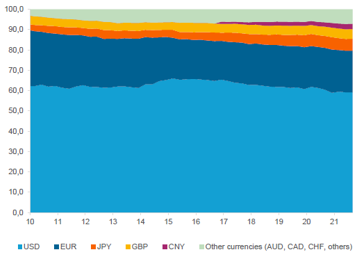

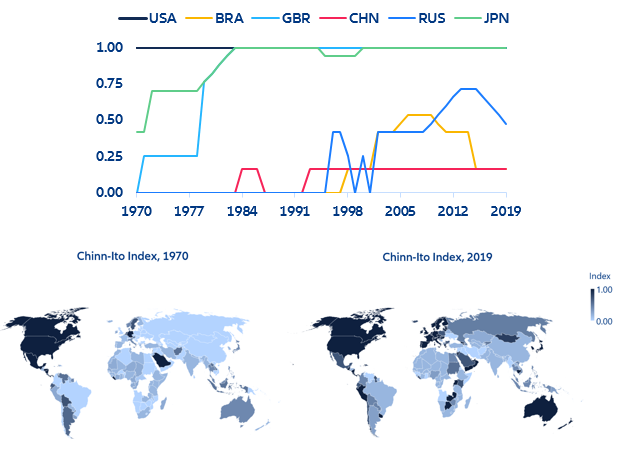

- Beyond the effects on Russia’s currency, the “weaponization of finance” aimed a paralyzing Russia’s economy could also have long-lasting consequences on the global financial system. While some of the sanctions, such as the freezing of almost two-thirds of Russia’s FX reserves, were politically expeditious, they also raise questions about financial sovereignty in a strongly USD-dominated monetary system. We could reasonably see some countries start diversifying away from the US dollar and/or the Western-dominated global financial architecture over time, especially those that feel they could be targeted by sanctions at some point. Furthermore, Russia’s short-lived gold-fixing might serve as blueprint for a more serious attempt by countries that have sufficient gold reserves (or commodities exports) to depart from the current system of fiat currencies.

Russia has managed to avert a currency crisis despite heavy sanctions.

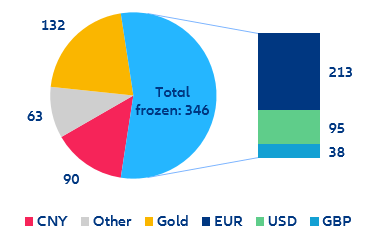

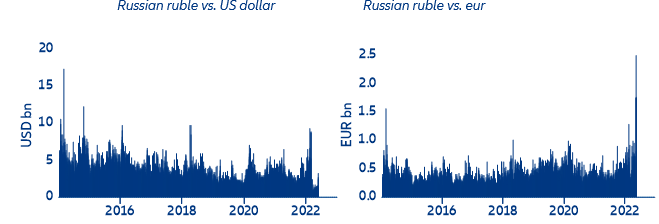

While the concept of the “weaponization of finance” is not new, it reached an unprecedented scale in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Overnight, about 55% of Russia’s USD630bn of pre-war FX reserves (Figure 1) were frozen and therefore unable to be used, leaving the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) mostly with domestically held gold reserves. In addition, the exclusion of most Russian banks from the international SWIFT payment messaging system, which was eventually broadened to also include the termination of correspondent bank relationships, made it virtually impossible for Russian banks to transact with their Western peers (Annex, Table 1). These financial sanctions were accompanied by export bans across different sectors, the blacklisting of certain supplies and targeted restrictions on economic activities by companies and individuals, including a partial embargo on energy exports. However, sanctions did not completely close Russia’s external account. Key commodities-related companies and banks were not affected by the sanctions, which has allowed the gas and oil flows to continue, but also money inflows into Russia.

Figure 1: Russia - International reserves by currency (January 2022, USD bn)