EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

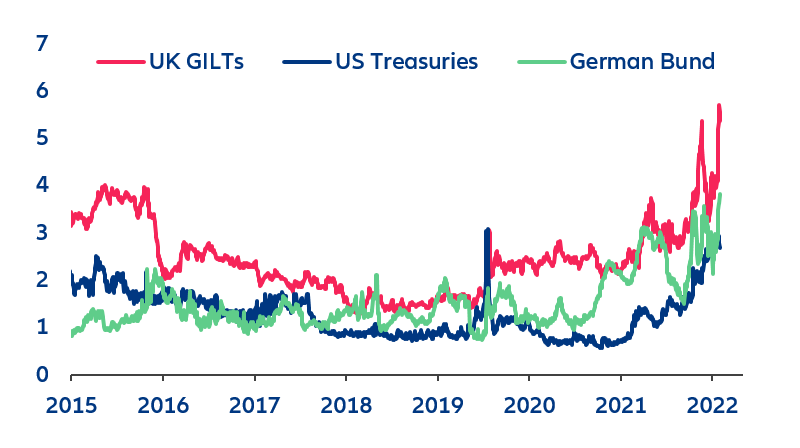

- The gilt crash inthe UK was not a repeat of the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis, but rather a liquidity-induced market accident that put financial stability at risk. As credit-default swaps (CDS) for the UK did not follow the surge in sovereign yields, liquidity risk caused the movement in gilts, rather than credit risk. It was also not a financial dominance conflict between central banks and markets as the Bank of England acted as a backstop for and not against markets. In our view, the high risk to financial stability will make more central banks likely to exert upward pressure on short-term rates while keeping long-term rates under control.

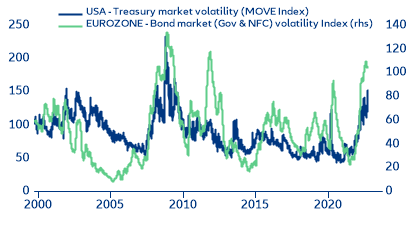

- Trading on the gilt market will continue to be bumpy for a while. But the UK is not an exception when it comes to liquidity risk. It was affected first because of the unfortunate interaction of monetary (tightening) and fiscal policy (easing) signals. Similar liquidity squeezes may develop, mainly in the Eurozone but also in the US since bond-market volatility has reached levels unseen since 2008-09 and safe collateral is still scarce.

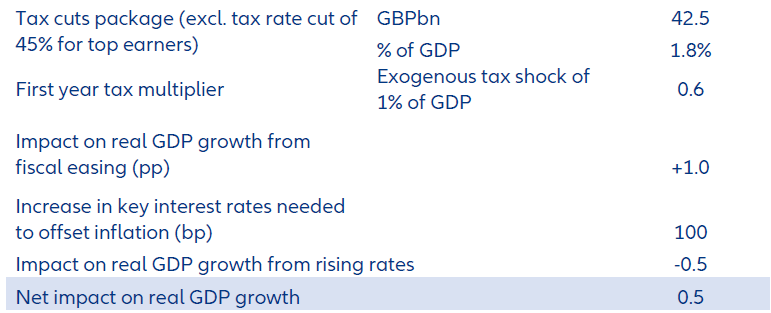

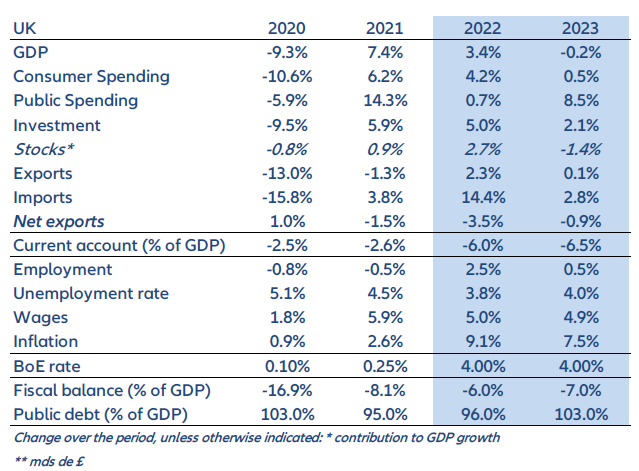

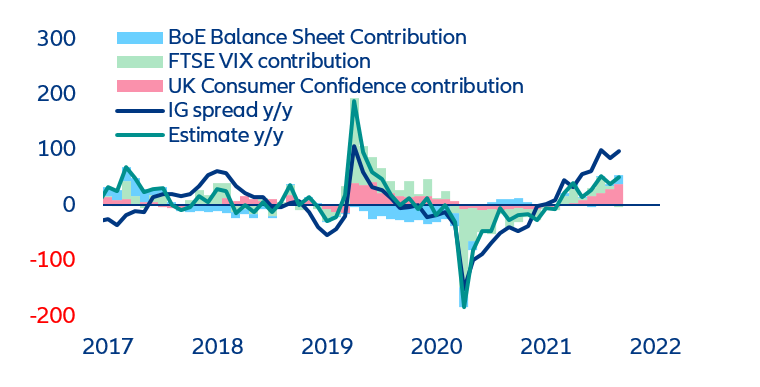

- We believe the BoE will need to remain the ‘lender of last resort’ beyond end-October and delay its quantitative tightening program to restore confidence. A real fiscal policy U-turn is also still necessary, going beyond the cancellation of the top 45% tax rate (which will save GBP2.5bn). As it stands, the fiscal package will push the UK’s fiscal deficit to close to -7% of GDP in 2023 and public debt to 103% of GDP. Hence, all eyes will be the medium-term fiscal path, which the chancellor is expected to present as early as this month, given the crisis. As +100bp higher sovereign rates equal to fiscal efforts of 0.5% of GDP for debt stabilization, and as general elections approach, the risk of fiscal slippage remains very high in a context of potential growth around +1%. As a result, it seems difficult for the BoE to start gilt sale operations of GBP10bn per quarter on 31 October, as currently planned.

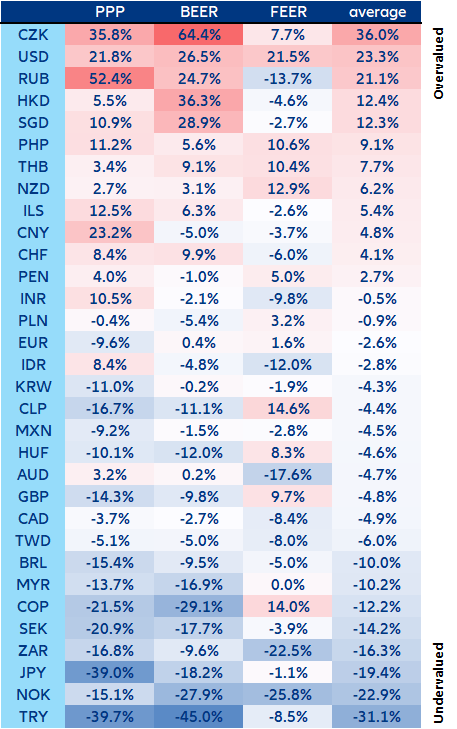

- In light of the high twin deficits, further GBP depreciation cannot be ruled out. We expect a decline of -7% against the USD if fiscal credibility is questioned again by end-November. In such a fragile environment, the BoE would be forced to hike interest rates faster (to 4% at end-2022, 150bp above previous expectations) but with limited impact on the GBP.

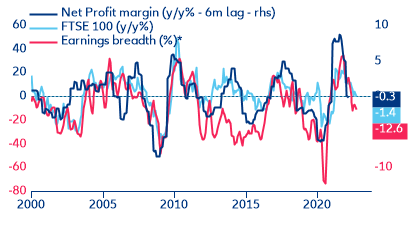

- Higher financing costs could push up corporate risk. The +150bps additional increase in rates will cut corporate margins by close to -2pp and push up corporate bank loan rates by +130bps. Cash buffers remain 35% above 2019 levels but are mainly concentrated among large companies. Hence, the potential liquidity stress coupled with the rise in energy costs will increase the share of SMEs at risk of defaulting to beyond 20% inthe UK, back to pre-Covid levels. Overall, we expect business insolvencies to rise to +15% above pre-Covid levels in 2023 (to 25,400 cases).

Markets immediately challenged the UK’s massive fiscal easing package, which was to be entirely financed by additional bills and bond issuance, even as the BoE was starting to sell gilts. Scrapping the tax cut for top earners is a step in the right direction, but more will be needed to get to a credible medium-term path. On 23 September, Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng announced an ambitious spending package of around 7% of GDP (or more than GBP200bn) over the next two years to fight the energy crisis. The package included GBP45bn of tax cuts, expected to be funded by additional borrowing, and represents the biggest fiscal easing since 1972, GBP15bn larger than expected. It is equivalent to more than 50% of the total Covid-19 package and should push public debt to 103% of GDP in 2023, from 96% in 2022, creating a budget deficit of -7% of GDP.

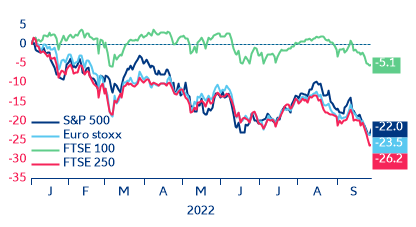

The announcement of the fiscal stimulus when the UK already has a sizeable current account deficit (see Table 2), and when the Bank of England was set to start quantitative tightening, triggered a crisis of confidence in the markets. The pound plunged against the US dollar on 23 September (-3.5%), reaching its lowest level since 1985. While the BoE’s recent announcement of engagement in targeted QE purchases of long-dated gilts has given some relief to the markets, the effect will certainly be short-lived as the reasons of the sell-off have not been fully addressed. The U-turn in the tax cuts for higher incomes has given some breathing space to the currency, but there is still a long way to go to recover fiscal and government credibility. After all, this part of the package costs the least and doubts about the financing of the fiscal deficit have yet to be clarified.

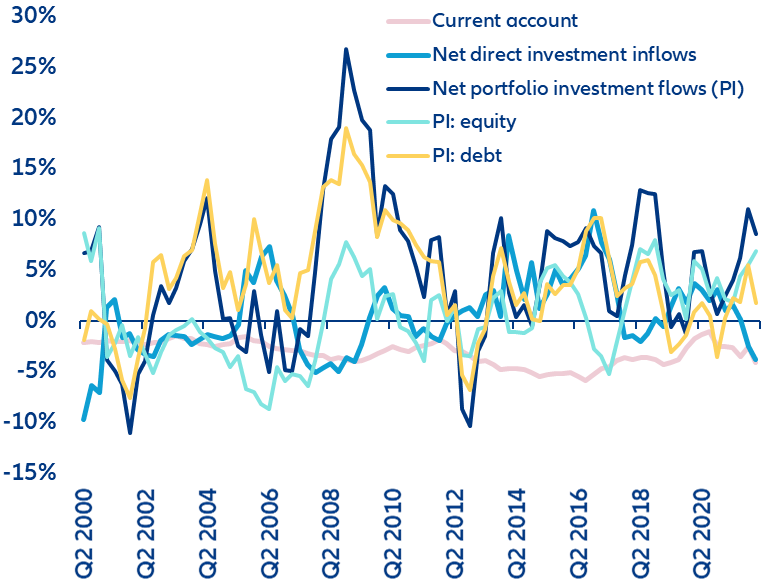

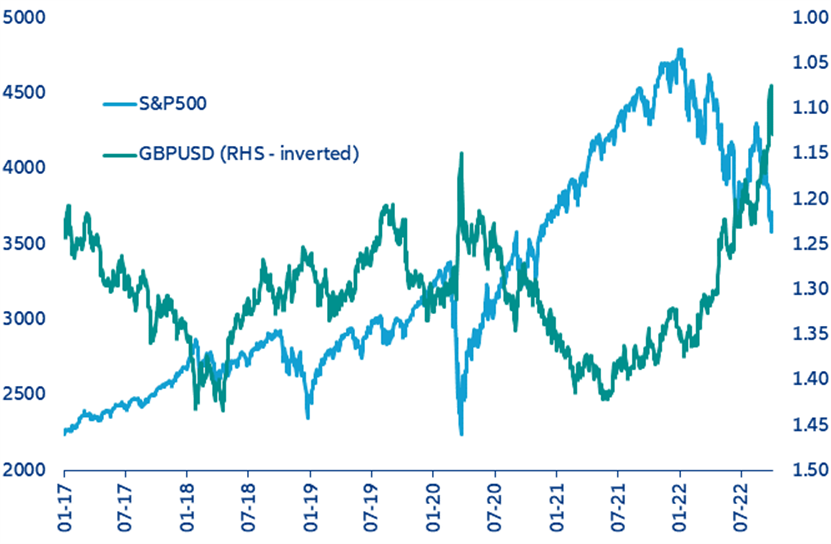

Portfolio investments have been an extremely important source of external-account funding inthe UK (Figure 1), especially in recent years. However, problems can certainly arise if investors lose confidence in the country. For the GBP, this could be a major issue as the currency has been highly negatively correlated with risk aversion (Figure 2). In the case of a ‘sudden stop’ of capital inflows, the current account would be forced to almost immediately reverse and this would in turn trigger a (further) depreciation of the currency.

Figure 1 –Balance of payments (4q rolling sum, % GDP)