Executive Summary

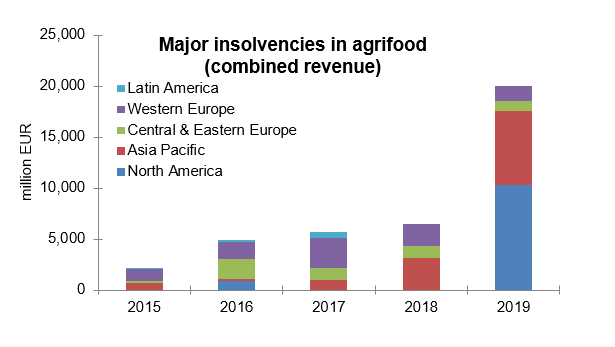

- Major insolvencies are on the rise in the global agrifood industry. At first glance, the global agrifood industry appears to be performing well, helped by the growing global population, especially in Asia. But since 2017, the sector has seen more than 30 major insolvencies on average per year, and the combined revenue of insolvent agrifood companies skyrocketed from USD6.4bn in 2018 to USD20bn in 2019.

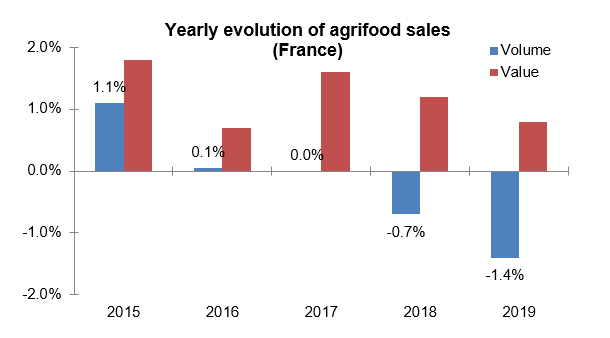

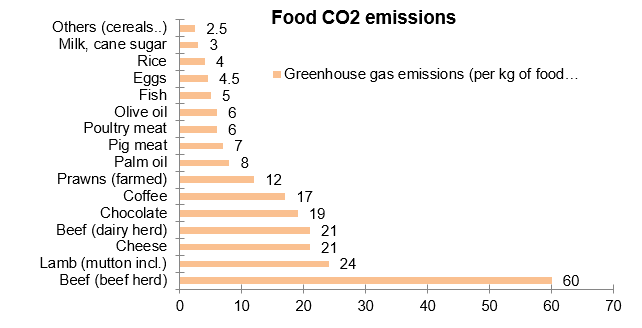

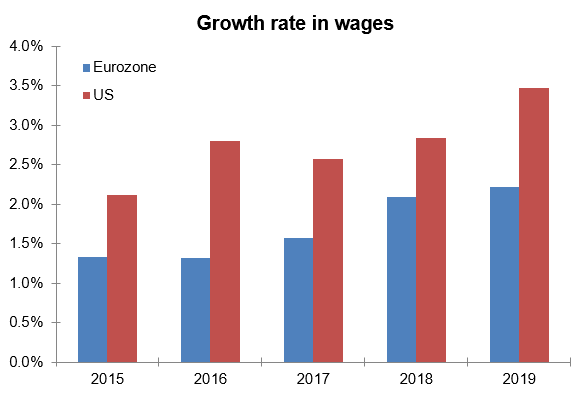

- Companies are facing five new challenges. These include: a change in eating habits, especially in the West, with consumers seeking out healthier foods; the need to reduce the carbon footprint of food production; trade disputes that are forcing companies to diversify food supply channels; upside pressure on wages, which account for 11% of all operating costs in agrifood and the inability of food processors to pass higher input costs on to customers due to a lack of pricing power.

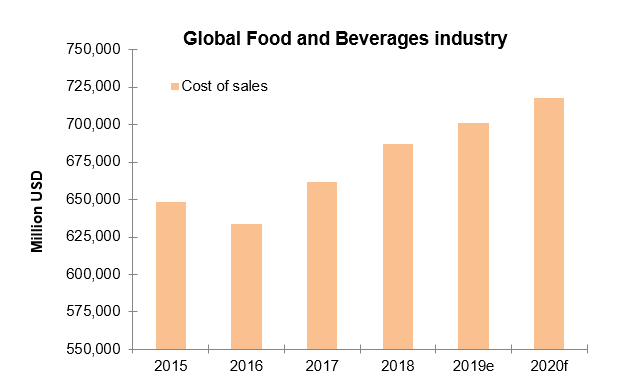

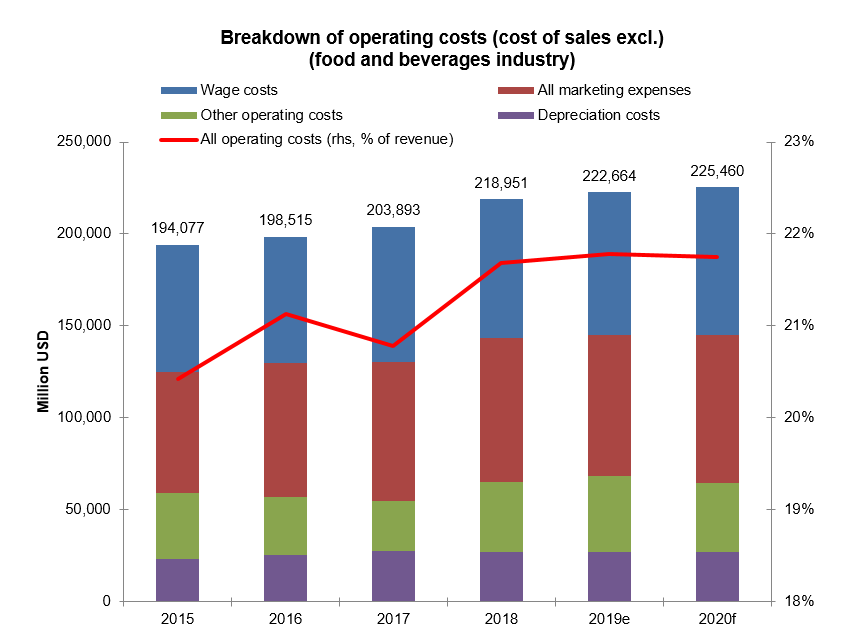

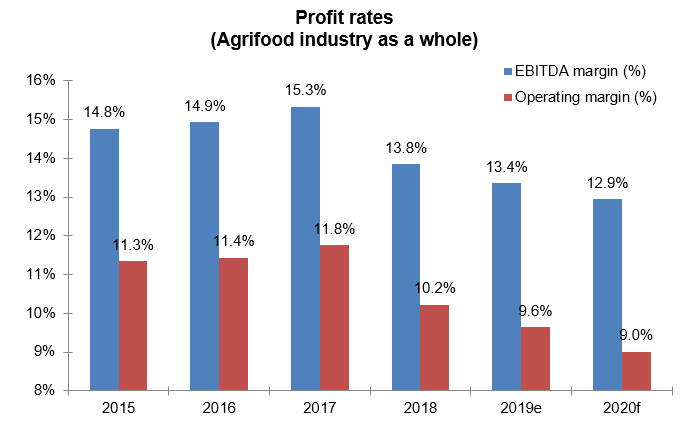

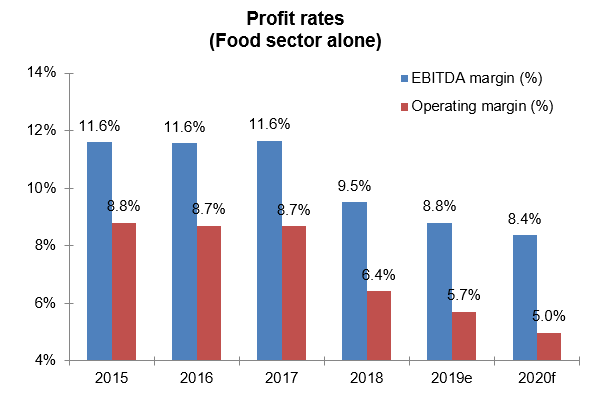

- What do these new risks mean for agrifood companies? We expect further deterioration in the operating margin rate of the whole agrifood industry, down to +9% in 2020 in comparison with +10.2% in 2018 (i.e. down 1.2 percentage points over the last two years on a global average). Overall, agrifood operating costs expressed as a % of revenues will increase by +1.4 percentage points to 21.8% in 2020, from 20.4% in 2015, growing faster than the rise in revenues. Even if the sector is still not close to a loss position, the impact of these new risks on agrifood companies’ operating costs bodes ill for their future profitability.

Major insolvencies are on the rise in the global agrifood industry

At first glance, the global agrifood industry appears to be performing well, helped by the growing global population, especially in Asia. The sector, which encompasses agriculture, food and beverages manufacturers, was valued at USD4.7tn in 2019, up +1.7% per annum since 2010. And it ranks third after pharmaceuticals and IT in Euler Hermes’ sector risk matrix, with 22 out of 69 countries recording low-risk ratings. So, agrifood could be considered as a healthy sector.

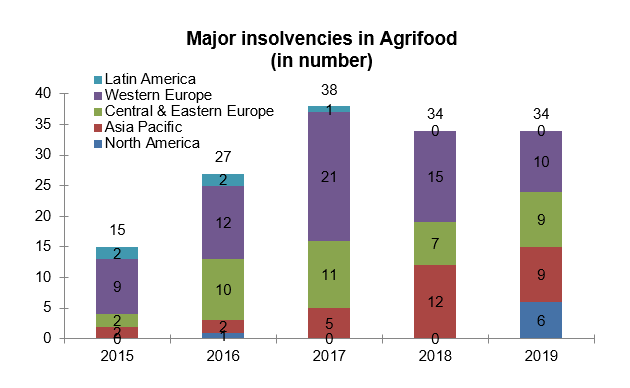

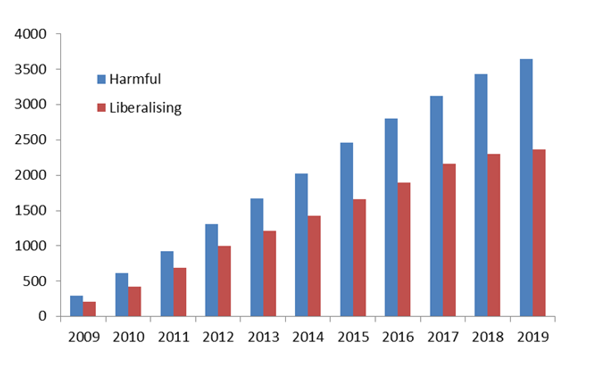

But several recent major bankruptcies raise concerns about the health of its main players. Since 2017, the sector has seen more than 30 major insolvencies on average per year (see Figure 1). And the combined revenue of insolvent agrifood companies (see Figure 2) skyrocketed from EUR6.4bn in 2018 to EUR20bn in 2019.

Figure 1: