EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

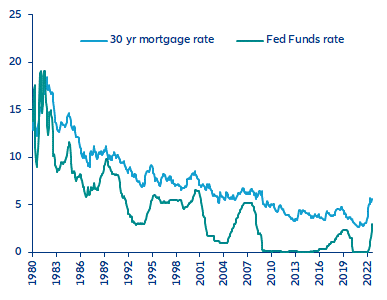

- The US housing market is adjusting to the new reality of higher-for-longer interest rates. Interest rates are rising rapidly – the Fed delivered a third consecutive 75bp hike during the September FOMC meeting – and unlikely to decrease much in 2023 as the FOMC will be keen to restore its inflation-fighting credibility. In this context, the pass-through from higher Fed Funds rates to mortgage rates today is the strongest since the early 1980s.

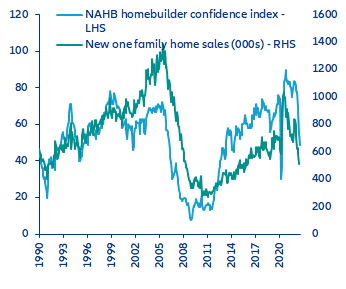

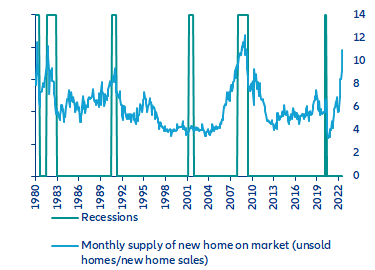

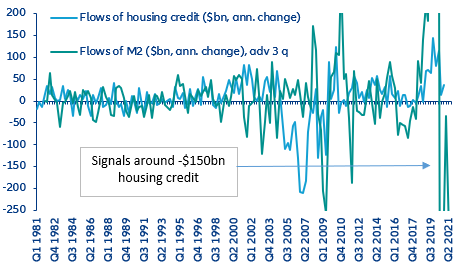

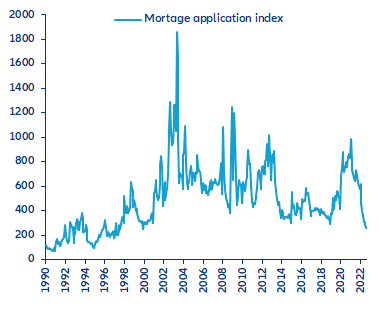

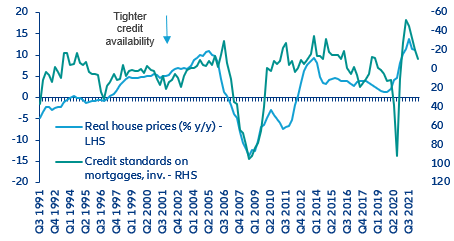

- As a result, housing and mortgage markets have entered into a rapid correction phase. Mortgage applications have slumped to their lowest level in more than 20 years, while the stock of unsold homes is reaching historical highs, signs that housing demand is dropping rapidly. Meanwhile, a rapid slowdown in deposits and monetary indicators suggests that financial institutions could start pulling back mortgage lending availability soon.

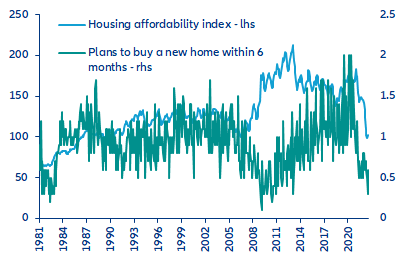

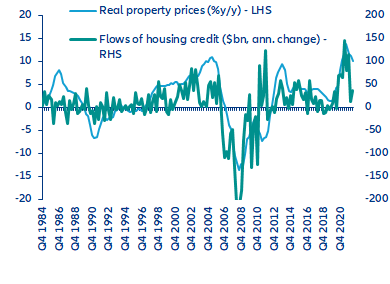

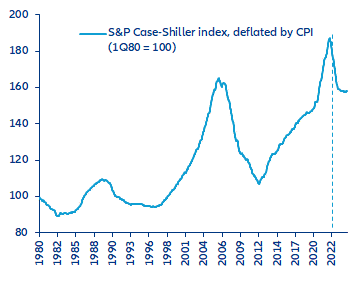

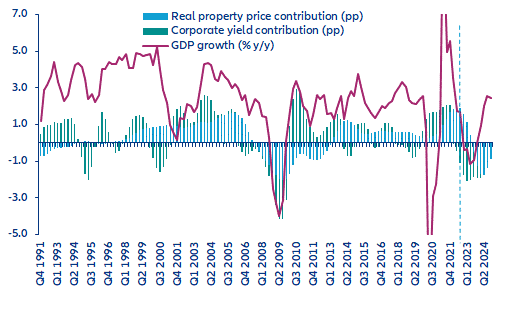

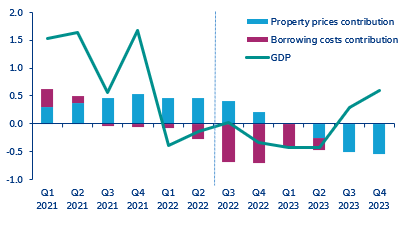

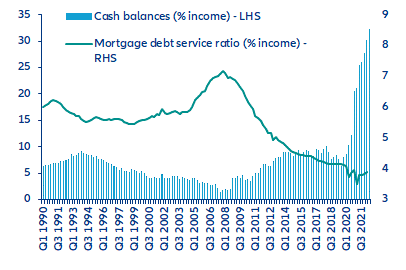

- Property prices have held up thus far but are the next domino to fall: We expect real property prices to slump -15% within the next 12 months, which will push the US economy into a recession in 2023 (-0.7%). However, strong aggregate household balance sheets should soften the blow. Unlike in the mid-2000s, household balance sheets are in better shape – overall debt is much lower relative to incomes, the average credit quality of that debt is higher (sub-prime mortgages have declined), net worth is very high (reducing the likelihood that large swaths of households slip into negative equity) and cash balances remain significantly above pre-pandemic levels.

The US housing market has entered into a sharp correction.

Mortgage rates are hitting the roof as the Federal Reserve tightens aggressively to cool off strong inflationary pressures. They started to increase abruptly as early as December 2021 when the Fed admitted that inflation was not transitory. By April 2022, the 30-year mortgage interest rate (the benchmark rate for most home mortgages) had shot up above 5%, compared to the all-time low of 2.7% reached in end-2020, and approached 6% by June 2022. It currently stands at around 5.7%. In fact, the current pass-through of Fed rates hikes into mortgage rates is stronger than that of any previous tightening cycle since the mid-1980s as markets expect the Fed to remain hawkish in the context of surging inflation (see Figure 1). Since the Fed pivot in December 2021, the average pass-through has been a little more than 100% (i.e. a 100bps increase in the Fed Funds rate translates into a bit more than 100bps increase in the mortgage rate) and is immediate.

Figure 1: Federal Funds & mortgage interest rates