EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

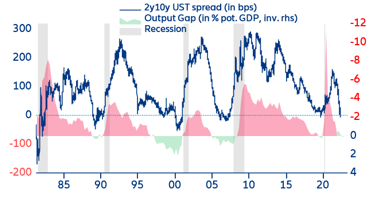

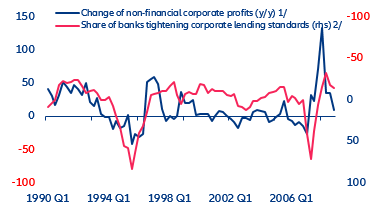

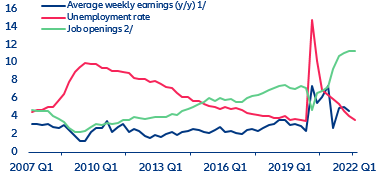

- The flattening (and partially inverted) US yield curve is signaling rising recession fears. There are signs that a rapid hiking cycle could narrow the window for a “soft landing” as a slowing economy amid elevated energy prices makes a recession increasingly probable. Corporate earnings have already halved from the recent peaks while the credit impulse has turned negative as banks have begun tightening their lending standards.

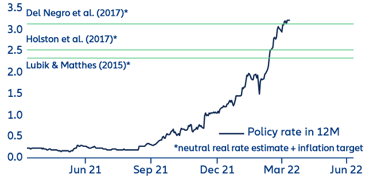

- However, the US economy has not reached an overheating phase (and growth is in fact slowing), with the policy rate still at record low levels. Corporate and household balance sheets have become less vulnerable to rising interest rates, thanks to rising cash buffers and lower leverage. But we believe the US Federal Reserve could raise the policy rate by not much more than 200bps without causing a recession, for instance, triggered by a collapse of the US housing market.

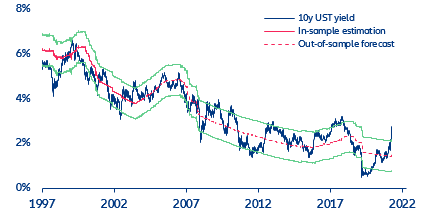

- Under baseline conditions, long-term rates have little room to rise further; however, in light of recent shift of the yield curve dynamics to longer maturities, the 10-year US Treasury yield could soon test the 3%-mark before declining during the remainder of the year.

The Fflattening (and partially inverted) US yield curve is signalling rising recession fears. But will they come true?

In response to the US Federal Reserve’s increasingly hawkish stance, short-term rates have risen by over 200bps since last September. And following the first rate hike in March, markets are now expecting a further increase of the Federal Funds rate by 150bps during the next three FOMC meetings at a probability of almost 70%. With US headline inflation reaching 8.5% y/y in March (and rising at its fasted pace since 2005 at 1.2% m/m) following a surge in energy and food prices, these expectations are unlikely to change soon despite core inflation (i.e. after excluding energy and food prices) moderating to a monthly increase of only 0.3%. In this context, the US yield curve has increasingly flattened over the past few weeks, and in some parts even inverted, signalling rising concerns about an impending recession. The most iconic slope, the 2y10y Treasury spread, is extremely flat, flirting with inversion (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Slope of the US yield curve as recession indicator