EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

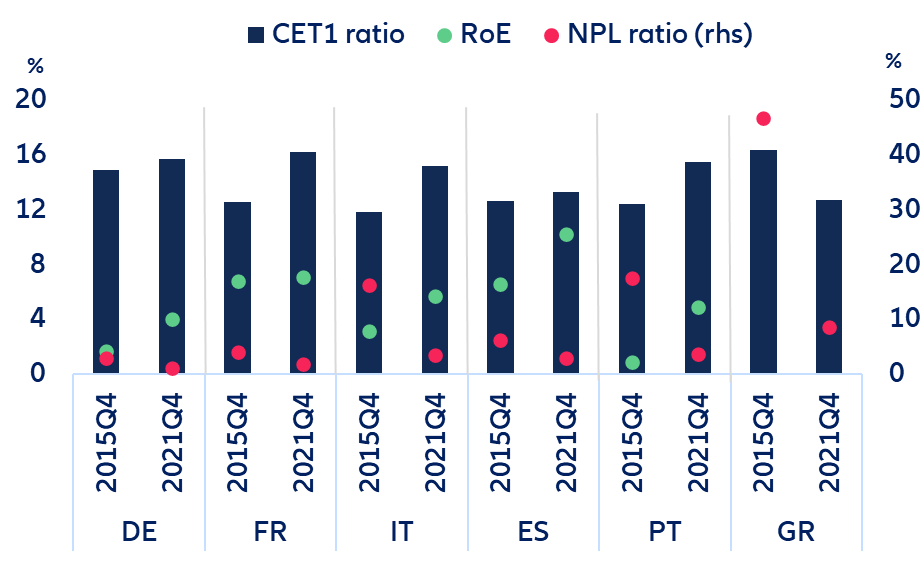

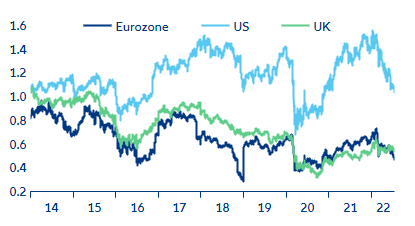

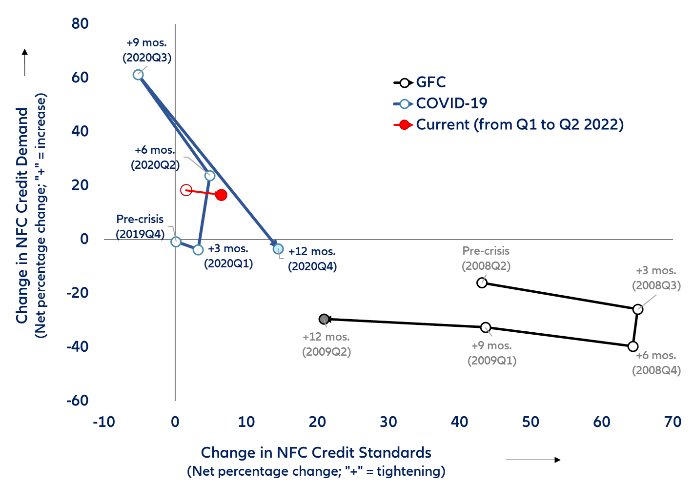

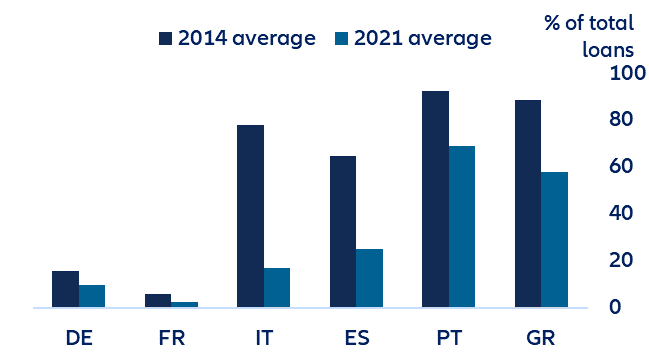

- After the ECB hiked interest rates for the first time in over 11 years today with a surprise 50bps-hike, could sharply tightening financing conditions spark a credit crunch? While banks are in a better condition compared to the sovereign debt crisis more than a decade ago, they have already become more risk-averse. The exit from crisis support measures will further constrain their ability to lend. Most debt moratoria and public debt guarantees have been phased-out and the third installment of the ECB’s TLTROs expired at the end of June, ending more than eight years of cheap access to central bank money. In this context, the private sector could face a considerable rise in funding costs, which could amplify the negative effects of inflation on consumption and investment.

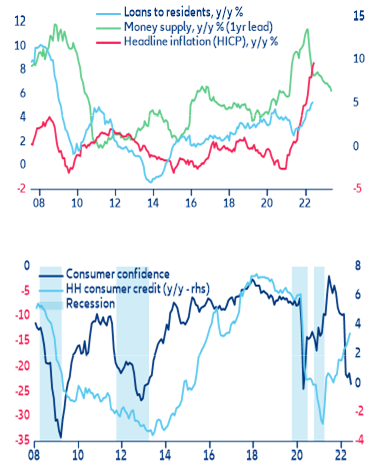

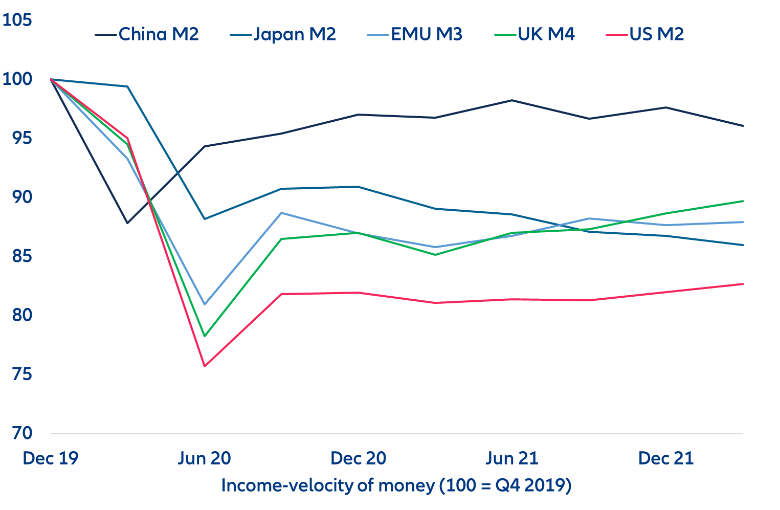

- With headline inflation reaching record levels, the ECB is understandably focused on keeping inflation expectations from de-anchoring. However, as banks’ rising risk aversion cause credit growth to slow, lower money demand should be disinflationary. Thus, sharply tightening credit conditions may sway the Governing Council to soon adopt a more gradual pace of policy normalization amid rising recession risks.

Would tightening financing conditions due to rising rates cause a credit crunch?

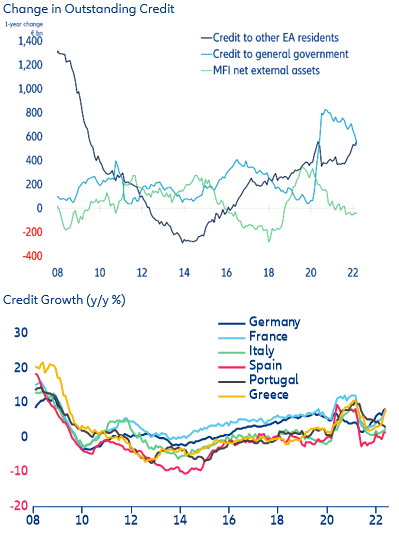

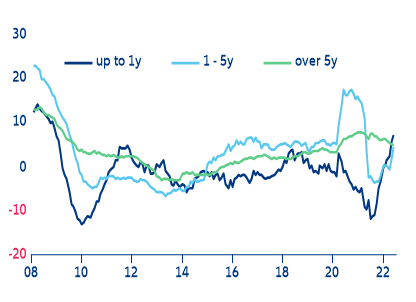

The ECB’s Governing Council front-loaded its exit from negative rates and hiked its policy rates by 50bps at its meeting today. Yet, credit conditions are already starting to show the first cracks amid the deteriorating economic outlook. While the overall credit impulse has remained positive as private sector lending remains buoyant (overall credit growth reached 5.7% y/y last month, mostly driven by commercial lending), current credit dynamics seem to be explained by a rotation away from (contracting) public sector lending (Figure 1). In addition, the lending rate for new loans to SMEs (proxied by loans with a nominal amount of up to EUR1mn) relative to larger firms has declined significantly across Eurozone member countries. Lending rates have been between 1.4% and 3.8% during the first five months of 2022 (compared to between 2.7% and 7.2% during the first half of 2012 at the height of the European sovereign debt crisis).

Figure 1: Eurozone - credit growth and net external assets of monetary financial institutions (MFIs)