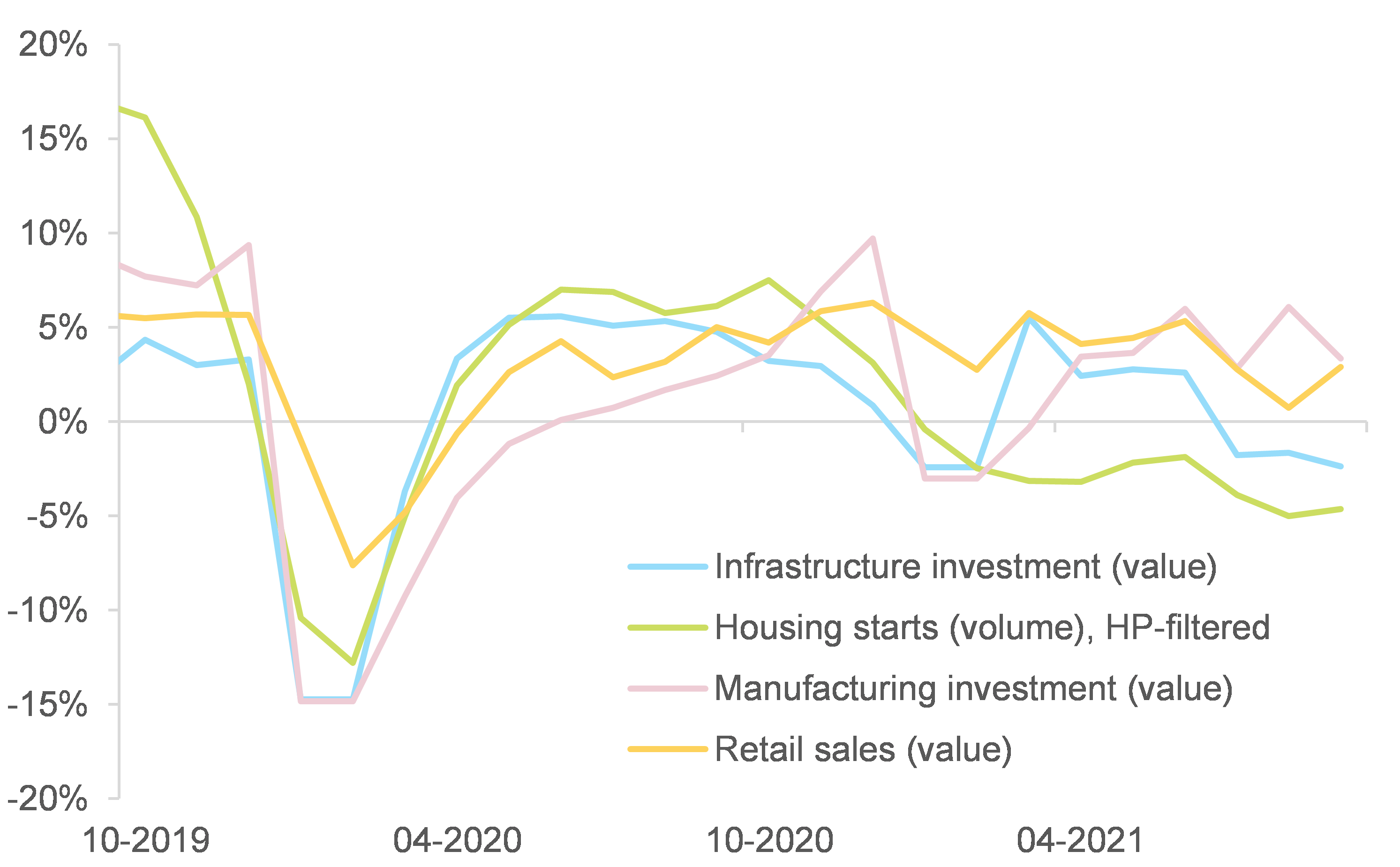

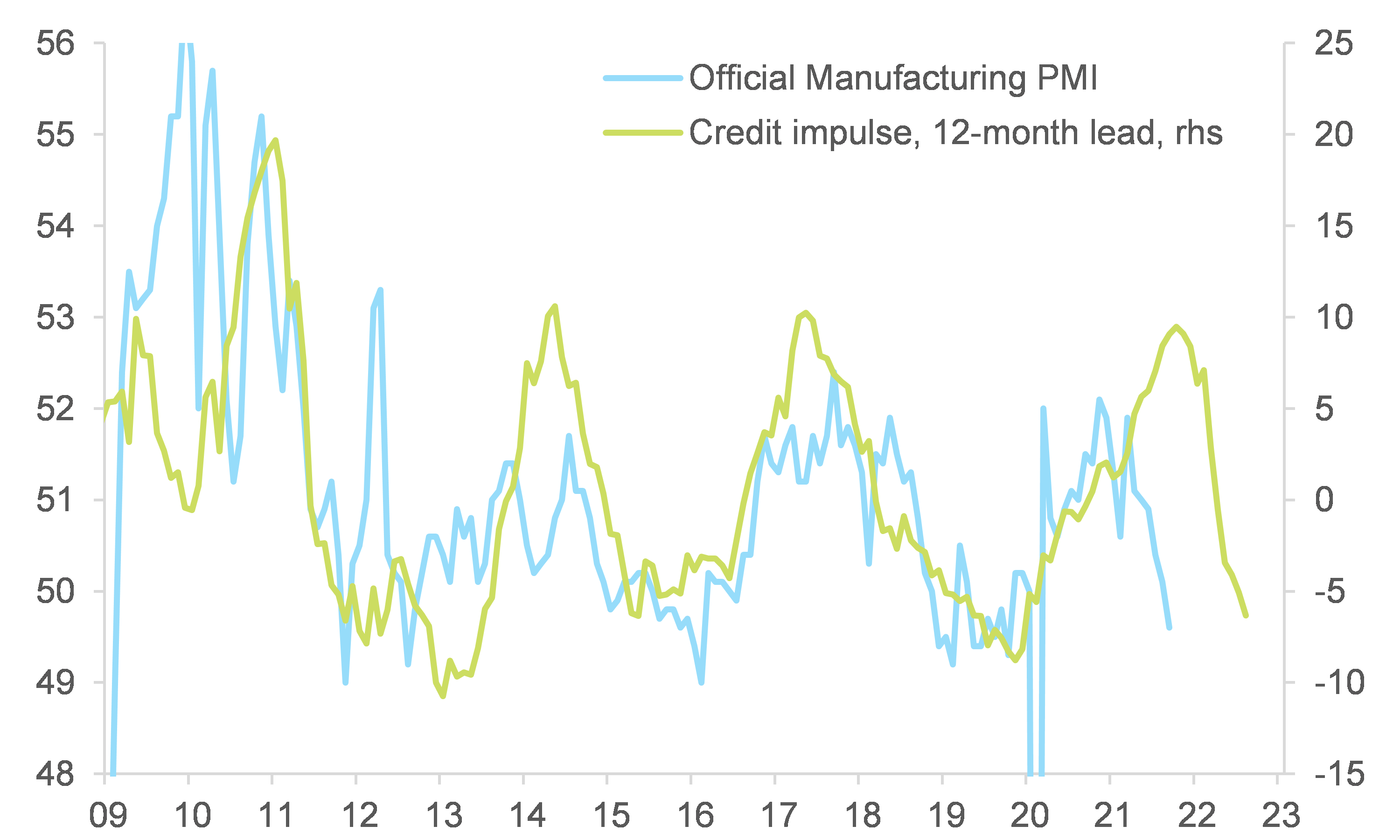

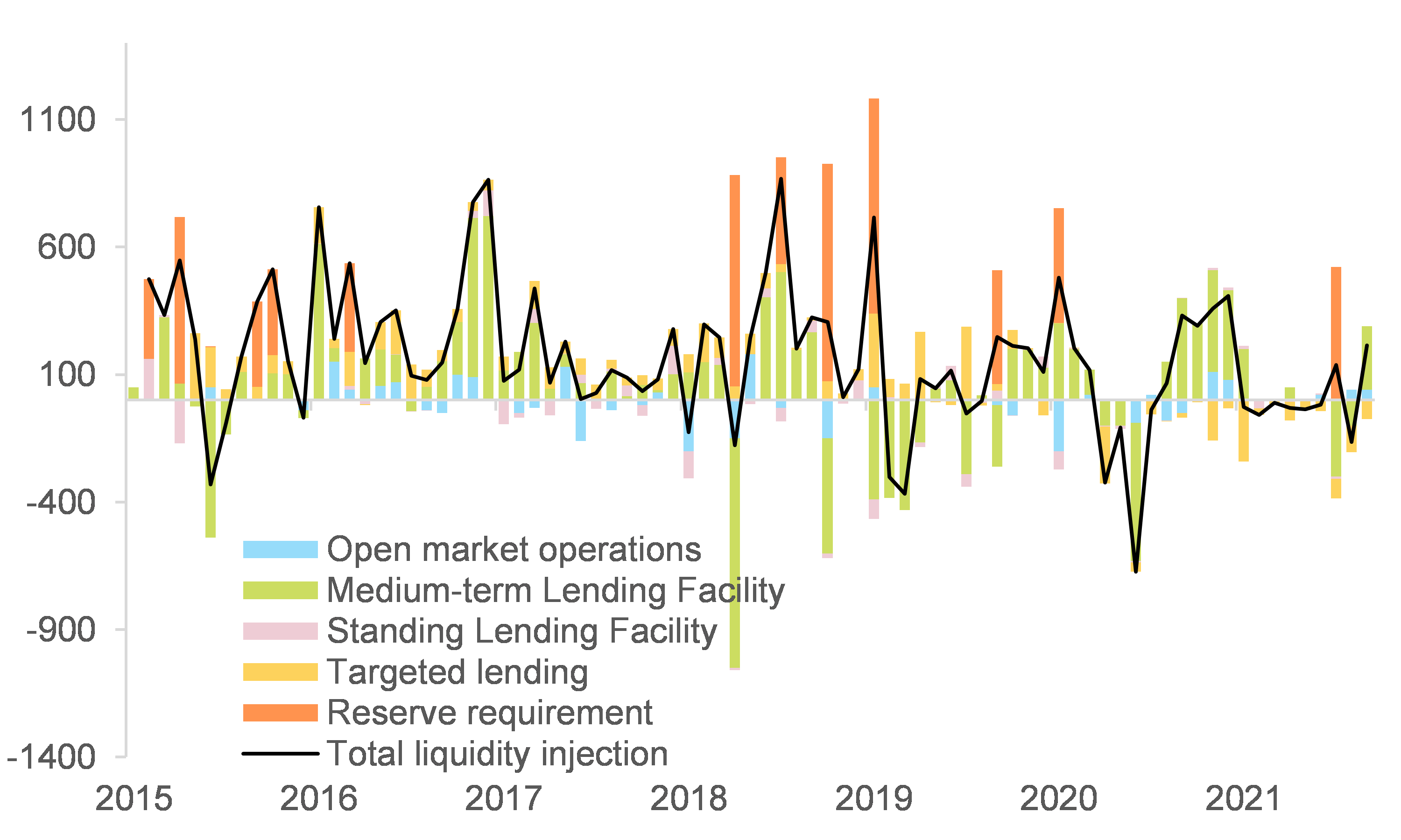

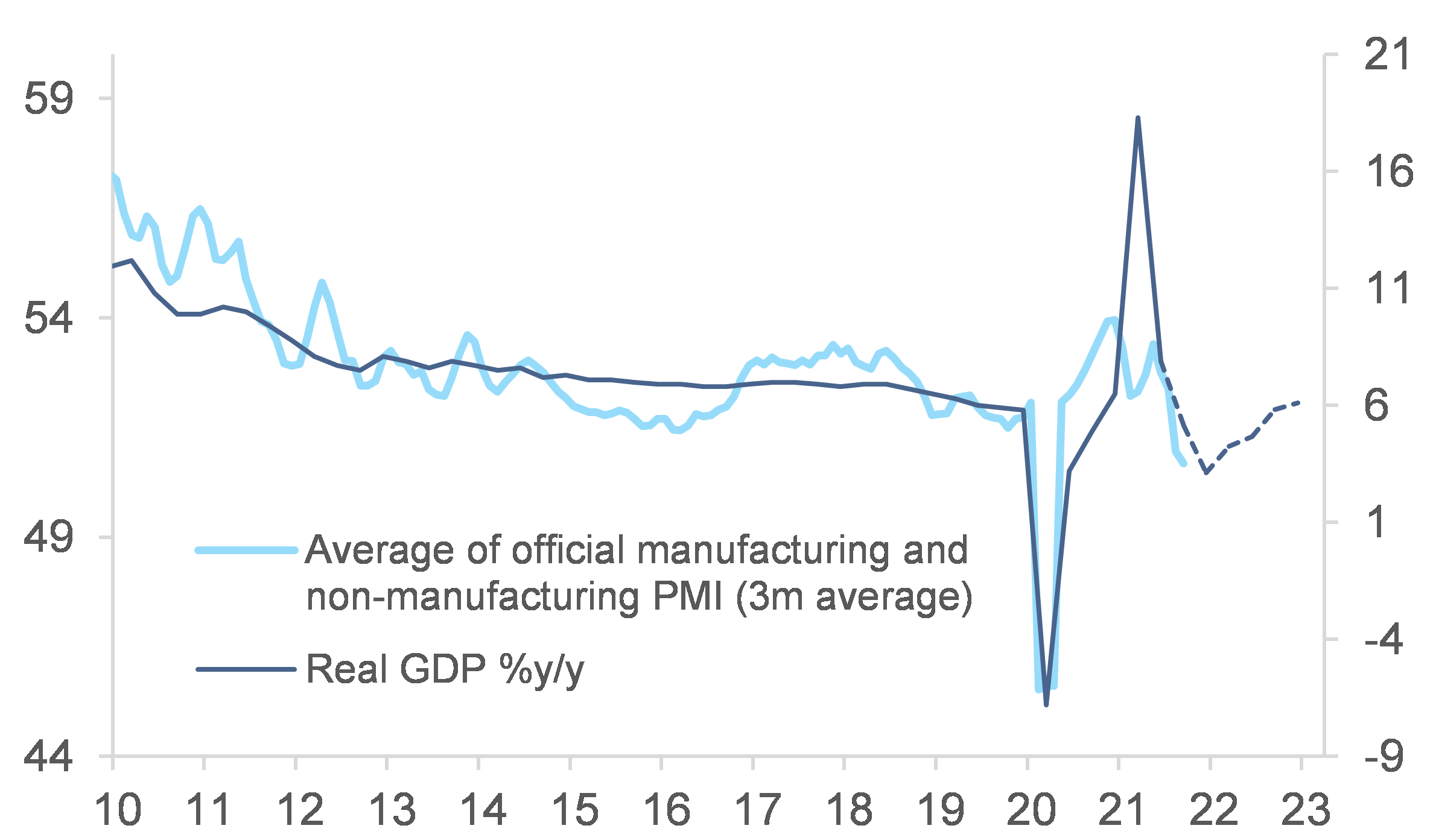

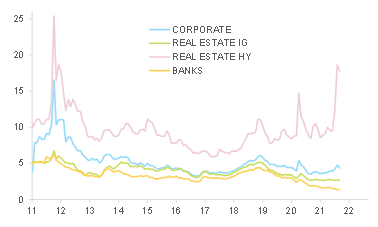

A mix of temporary and policy-driven crunches, the biggest being real estate, has sparked a sudden slowdown in China, which we expect to continue through Q4 2021 and the beginning of next year. As a result, we cut our GDP growth forecasts to +7.9% in 2021 and +5.2% in 2022, from +8.2% and +5.4%, respectively. This compares with consensus expectations at 8.1% in 2021 and 5.3% in 2022 as of October. Policy tightening and delta outbreaks have crunched cyclical activity but we do expect these factors to fade away. A recovery of services is likely going forward, although a return to normal will be hindered by the zero-Covid strategy likely to last well into 2022. In addition, “common prosperity” and increased regulatory scrutiny should keep industrial activity and the real estate sector under pressure. We expect at most a pause and/or softening of authorities’ communication in the regulatory crackdown against the real estate sector. This means that housing activity will remain weak and further defaults among real estate developers can be expected – even though policymakers have the means and intention to avoid a systemic crisis. Other areas of increased regulatory scrutiny include energy and local government finances, but they could be eased to mitigate the impact on short-term growth.

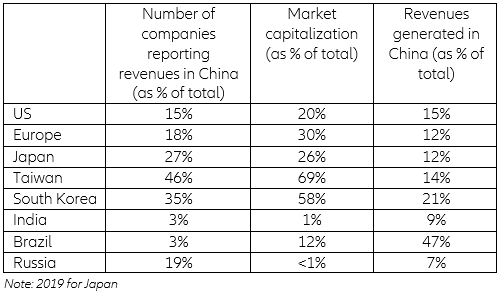

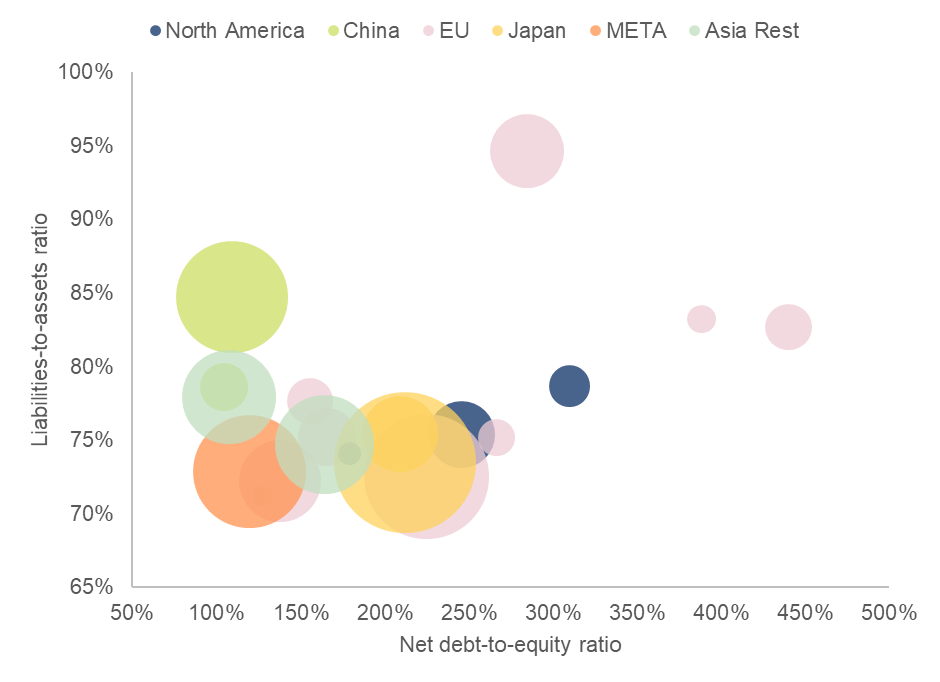

What could go wrong? The risk of policy mistakes has increased. We think risks remain tilted to the downside and much relies on policy coordination and reactivity to help the economy navigate the multiple crunches that are occurring at the same time. The main domestic risk comes from the real estate sector deteriorating further in a long-lasting way, with spillover impact on other sectors of the economy. Indeed, accounting for downstream and upstream sectors, final demand generated by real estate accounts for c.25% of China’s GDP and housing represents 78% of household assets, 40% of bank loans are backed by properties and land sales amount to roughly one-third of local governments’ gross revenues. The main external risk is geopolitical as renewed tensions emerged in the Taiwan Strait and with the US. The likelihood of an actual conflict remains extremely low and we continue to expect a status quo in US-China trade tariffs, although non-tariff barriers could increase. In the long run, the situation denotes the US’s intention to further deploy its containment strategy against China.

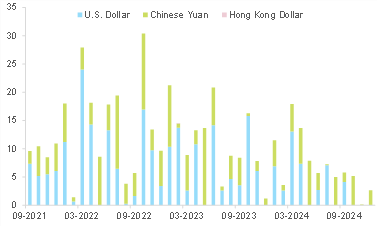

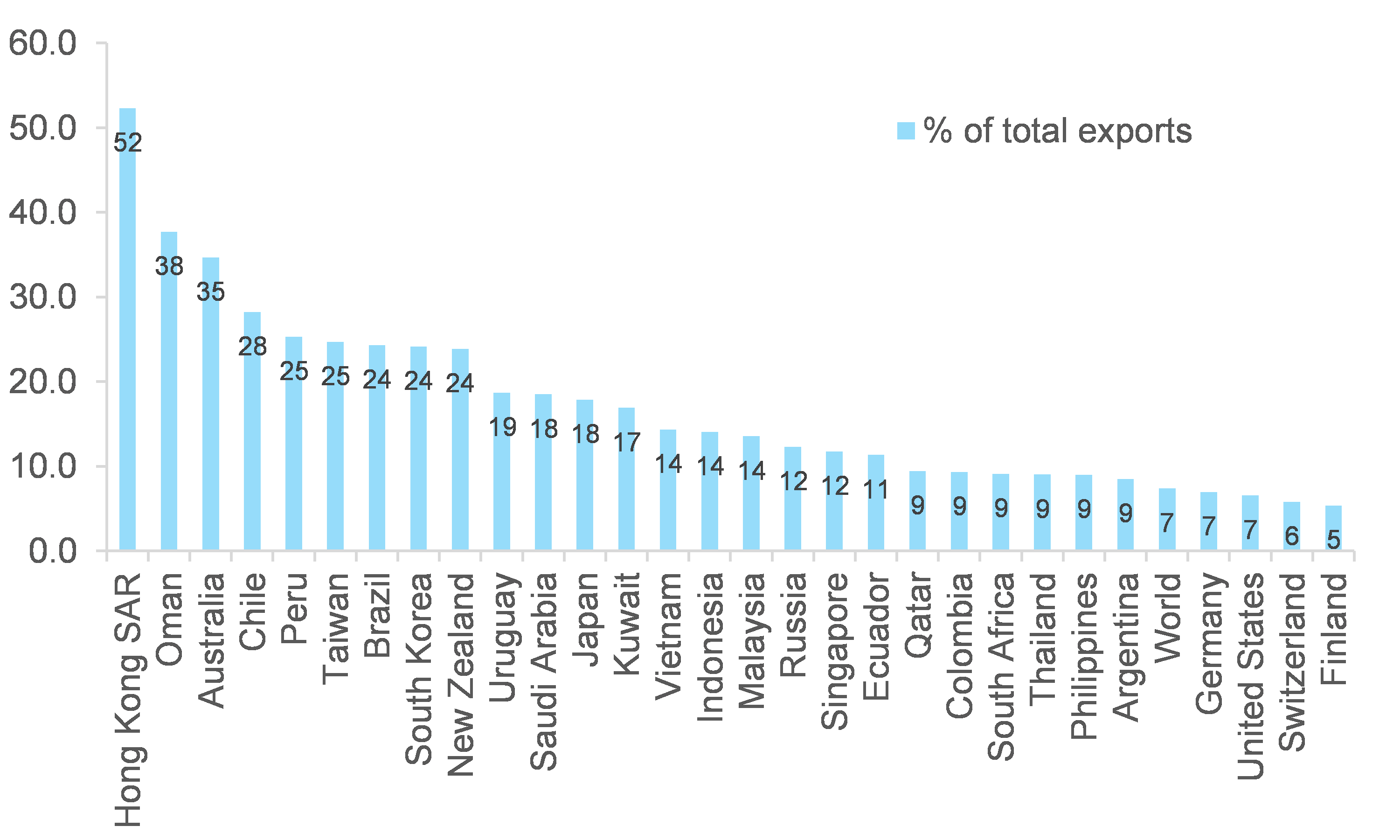

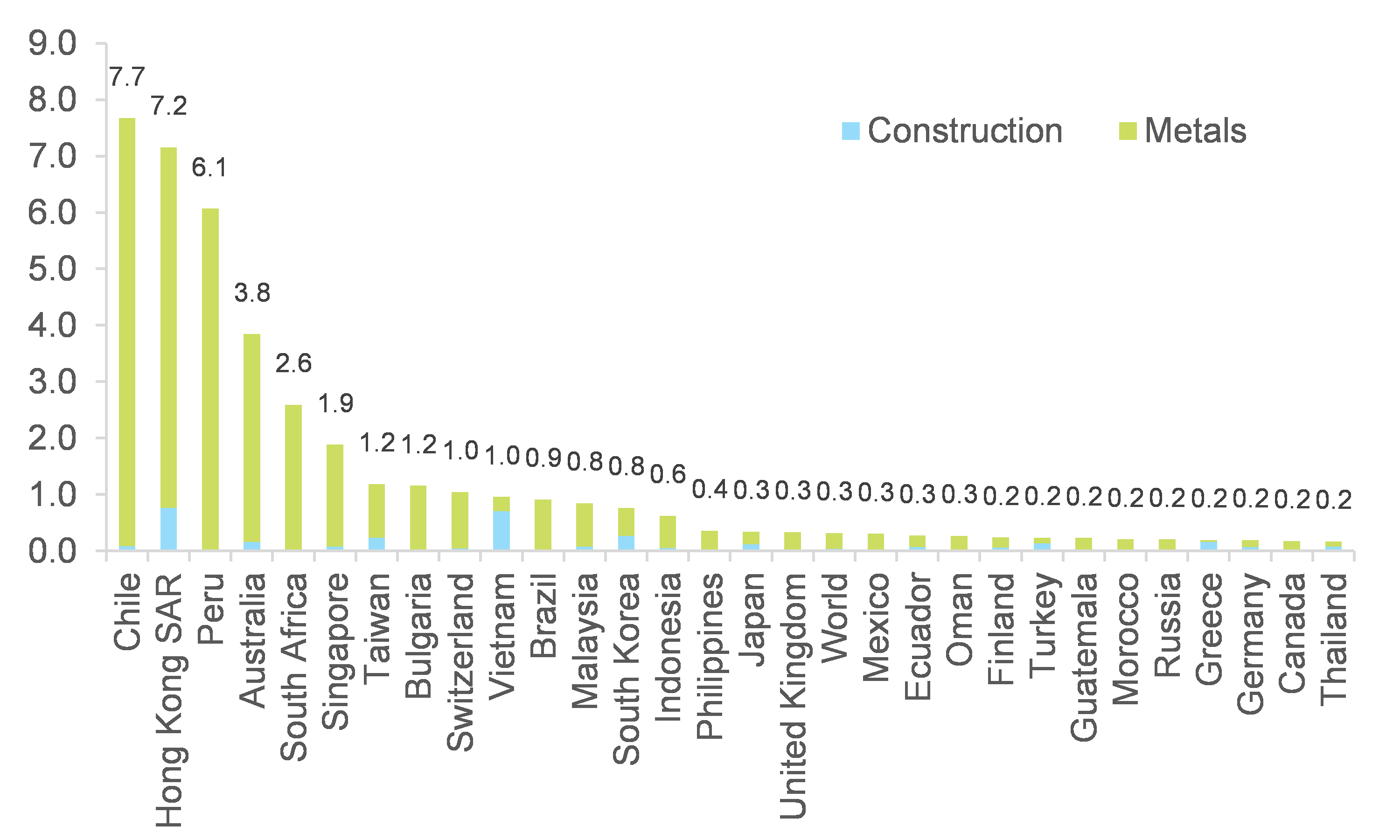

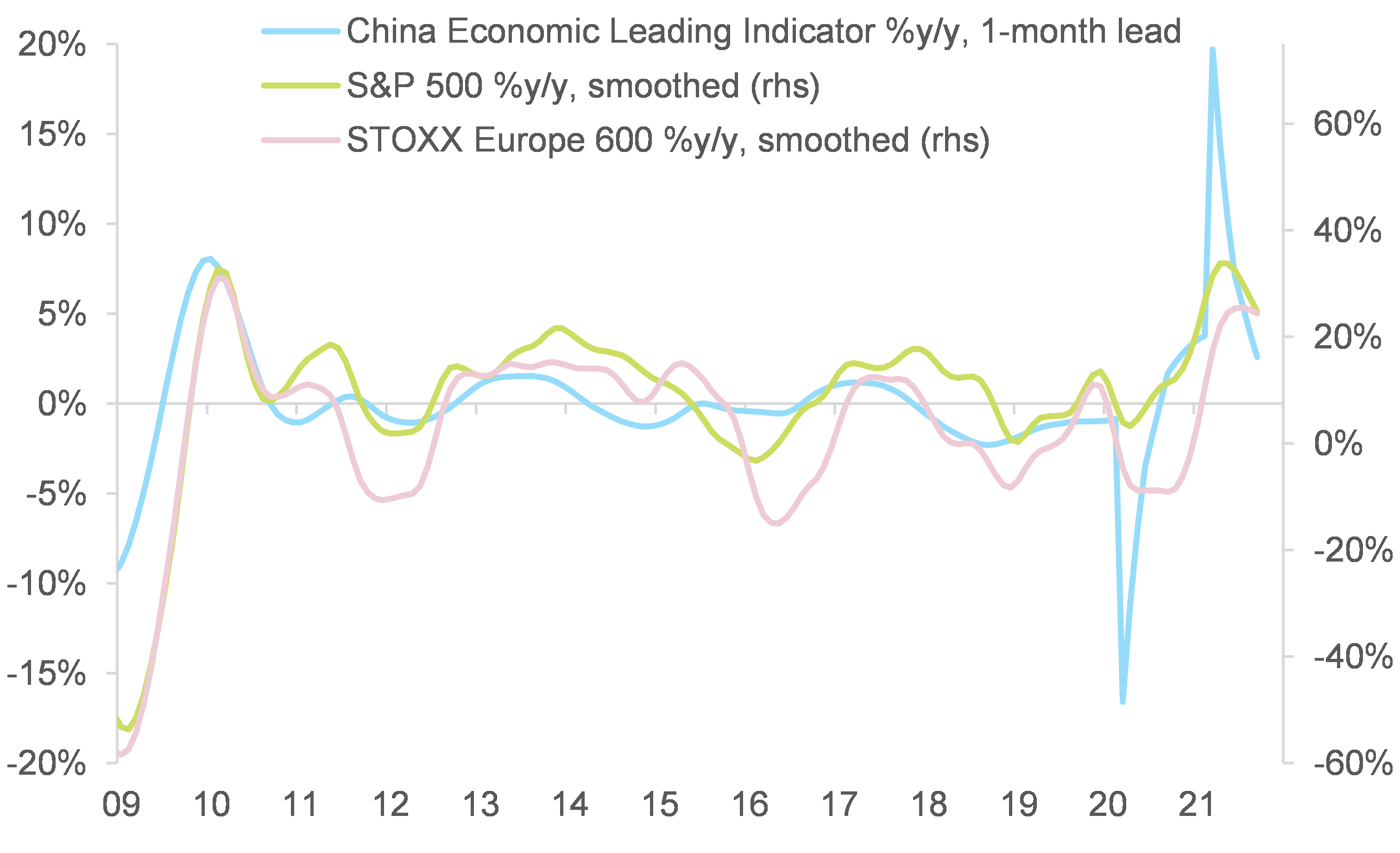

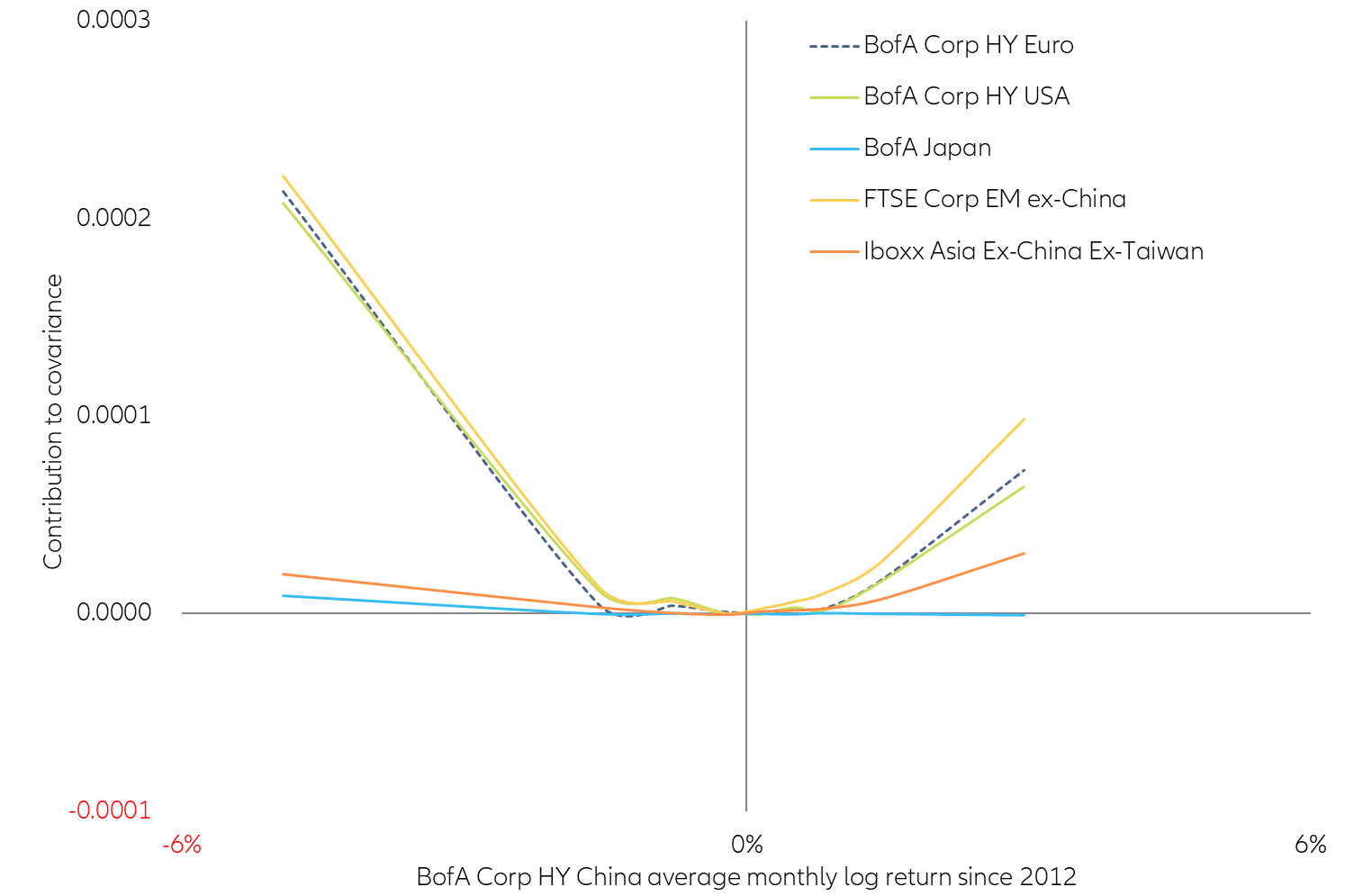

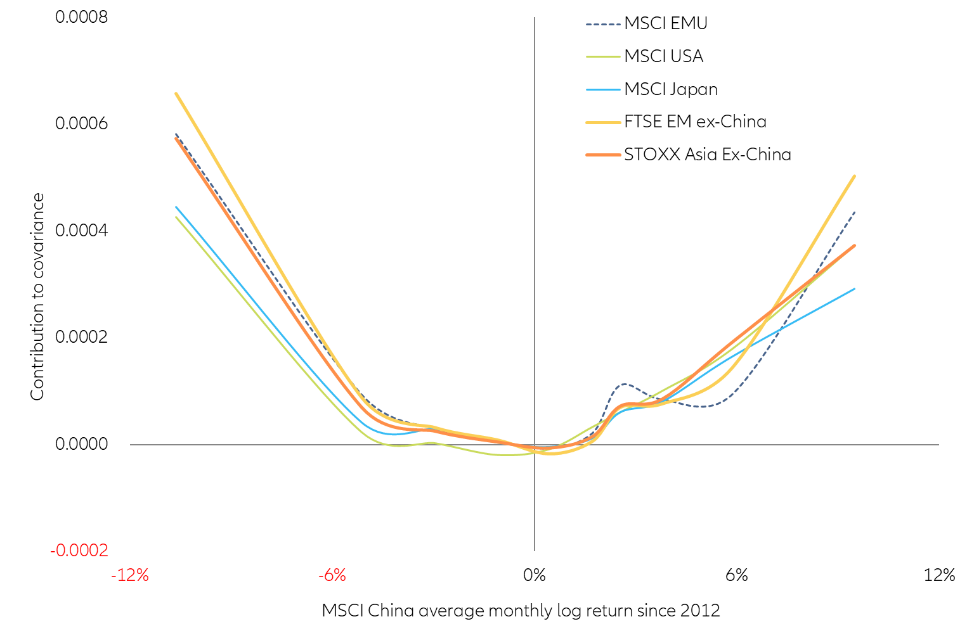

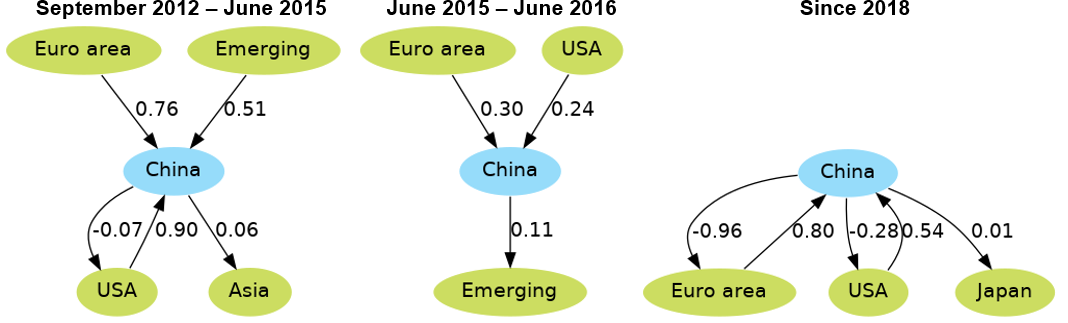

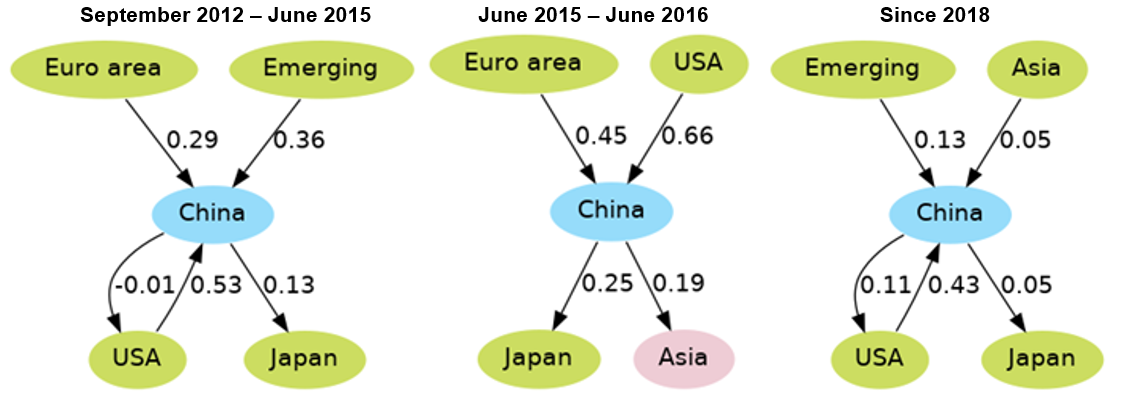

What does China’s slowdown mean for the rest of the world? From a global supply perspective, the Chinese economic slowdown could further raise the cost of trade and global input prices, lengthen delivery delays, and even worsen production shortfalls in the US and Europe. From a global demand perspective, exporters to China could suffer, particularly those exposed to the construction and metals sectors (i.e. Chile, Hong Kong, Peru, Australia and South Africa). Conversely, exporters of energy and more precisely thermal coal (particularly in Indonesia, Malaysia and Australia in Asia-Pacific) are likely to see rising demand in the context of the ongoing energy crisis in China. Beyond the short to medium term, countries dependent on Chinese demand will need to deal with its adjustment to a lower growth regime (average between +3.8% and +4.9% in the coming decade), and the ensuing risks. The changing economic model could also alter exporters’ exposures (heavy industry and construction vs. consumption and high technology goods). Looking at financial markets, we find that spillovers from China to the rest of the world are more likely in equities than corporate credit, but in both cases more likely in the event of significant negative performance in China. During the 2015 China market crash, a -10% drop in Chinese equities would have driven Japanese and Asian equities down by -2.5% and -1.9%, respectively, while Chinese credit bonds falling by -1% drove down EM credit by -11bps (all other things being equal). Since then, access to Chinese assets have opened further, meaning that a market rout in China could have even more damaging consequences, and potentially well beyond Asia and emerging markets.