Executive Summary

- The COVID-19 outbreak has forced governments to put the world on an unprecedented pause, for at least three months, to flatten the contagion curve. In December 2019, when writing our last economic and capital markets outlook, What to expect in 2020-21: Defending growth at all costs, we did not know the title would be so ominous. Since January, the impact of the outbreak has unfolded from a China-centered supply shock, which sent shockwaves across global trade and disrupted supply chains, to an unraveling of financial markets as investors realized the unavoidability recession, to a violent demand shock hurting consumption and investment in China, Europe, and the U.S..

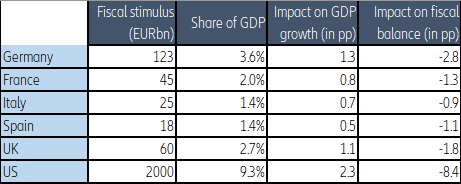

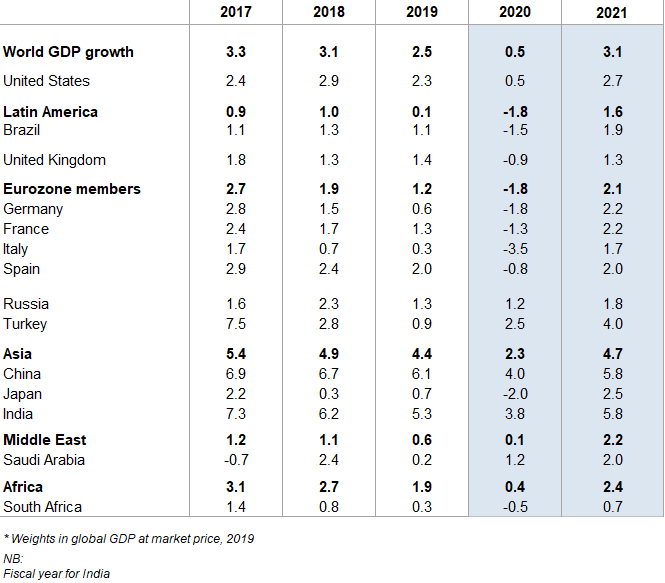

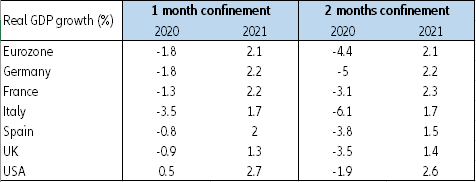

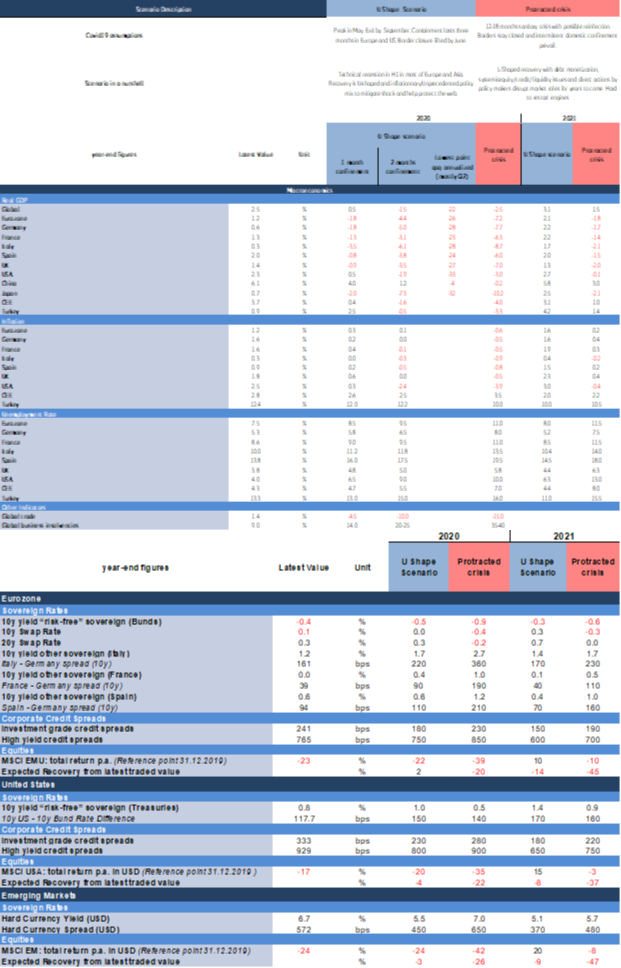

- Policymakers have taken extraordinary measures in extraordinary times to flatten the recession curve. In our central scenario, we expect a sharp global recession in H1 2020 in the vast majority of developed and emerging economies, followed by a U-shaped recovery. From the ECB’s EUR1.1tn to the Fed’s USD1.5bn liquidity provisions, to business-friendly fiscal responses across the globe providing 0.5-1.2pp of growth relief depending on the country, the aim has been to weather the cash-flow crisis, avoid a more severe liquidity crisis and protect the web. However, the cost of containment could be as much as a 20-30% shock to each economy for a month, if we draw lessons from the Chinese situation. In addition, the cost of a full quarter of disruption to global trade should be USD1064bn as more economies adopt strong confinement measures, including severe border restrictions. The recovery, starting in H2 2020, will certainly be commensurate with the shock, with temporary inflationary overshoot.

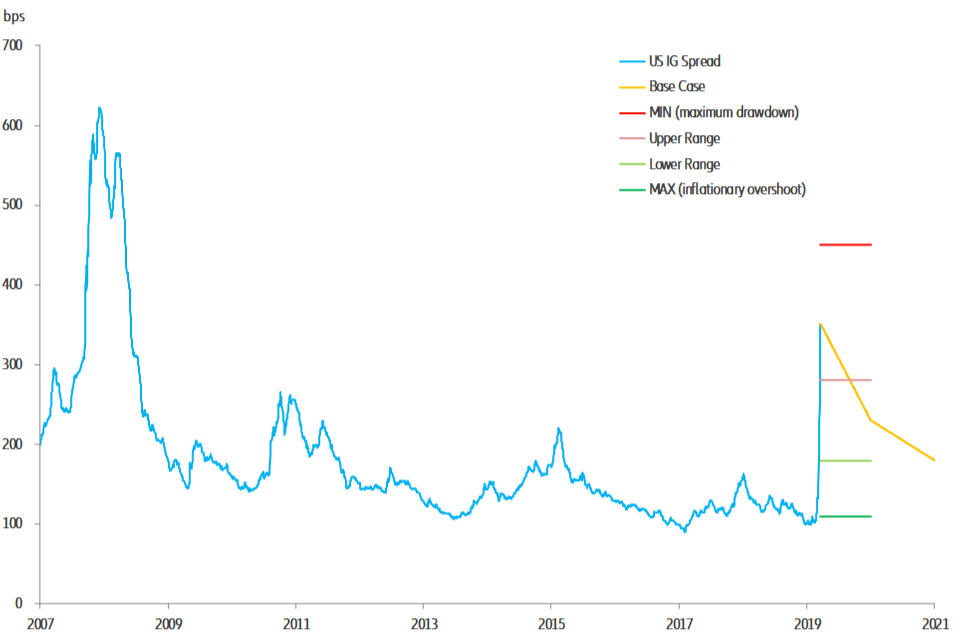

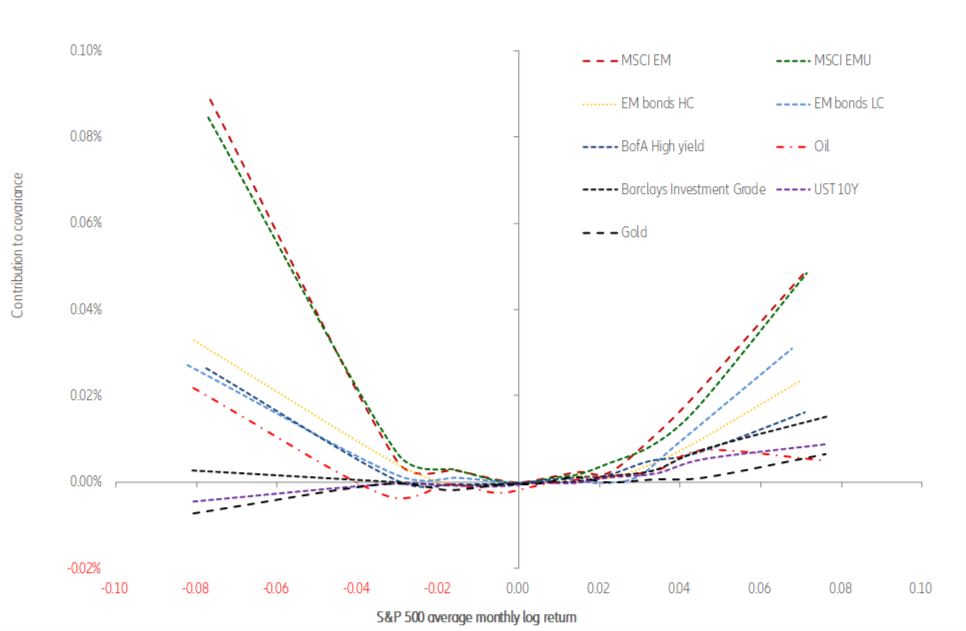

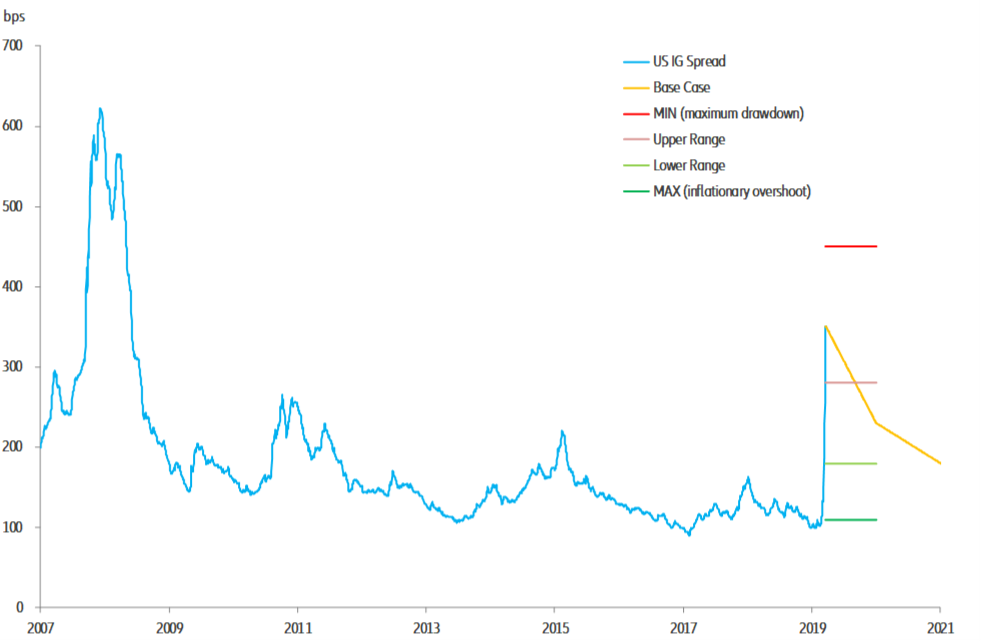

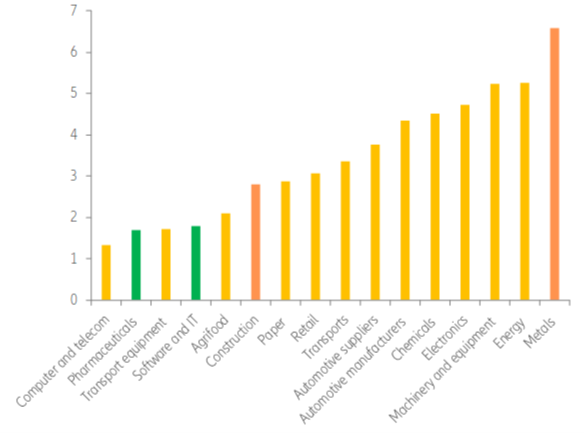

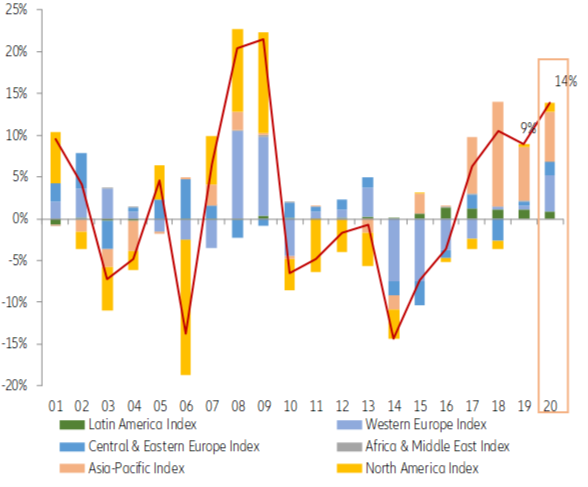

- For capital markets, it will get worse before it gets better. For companies, we expect insolvencies to increase by +14% worldwide in 2020. Markets are not yet fully pricing in the negative news flow coming with lockdowns affecting more than 50% of the world’s GDP. We expect short-term volatility to bring down equity markets by an additional 10- 20%, a 30-50bps downside correction in long-term sovereign yields and a 100bps widening trajectory in corporate credit investment grade spreads. However, we expect capital markets to gradually reverse the losses towards year-end as policymakers’ credibility and the U-shaped recovery unfold. As for companies, 2020 will be the fourth consecutive year of rising bankruptcies and though policymakers pledged to do whatever it takes to avoid unemployment and defaults, a wave of insolvencies when business starts again is very likely.

- What could go wrong? There are three canaries in the coal mine: corporate stress, liquidity and policy mistakes. In addition, we also run an alternative scenario of a protracted economic and financial crisis due to a 12-18 month health crisis (with possible reinfection). Regarding downside risks, sharp downward price movements in goods and equity markets would generate liquidity stress and credit events, unearthing fundamental weaknesses in the global economy just like in 2008-2009, including substantial stress on the corporate bond markets. Also, mind the risk of policy mistakes: as central banks and treasuries unwind unmatched level of support, the risk of relapse is high. This scenario would mean a continued recession into 2021, and an L-shaped recovery with debt monetization, systemic equity/credit/liquidity issues and more direct actions by policymakers that would disrupt market roles for years to come, with difficulty to restart the engines.

- Too early to draw lessons? The COVID-19 crisis will certainly change how we see: investments in health and define inclusive capitalism; China’s soft power; globalization; the fight against climate change, another exponential, probabilistic and collective challenge ahead of us and maybe how we save for life events.

Covid-19: From a health crisis to a triple shock on the economy

Trade recession, overvaluations and a fragmented world: 2020 started off on a weak note. First, global trade in goods and services had grown at its slowest pace since 2009 and the manufacturing sector had been in recession since Q3 2019. Trade grew at a bare +1.4% in volume terms and contracted in value terms, owing to the U.S.-China trade feud, the resulting manufacturing recession and shocks in the automotive and electronics sectors. The U.S.-China phase one trade deal partially dissipated uncertainty but failed to significantly decrease tariffs – duties remained on USD250bn of Chinese imports. Second, different markets were in over-valuation territory. In such circumstances, any shock of uncertainty could have a brisk impact on prices and liquidities, disrupting financing conditions for companies. Lastly, multilateralism had taken a blow as retrenchment policies were flourishing in the U.S. and neo-authoritarian emerging markets:, 2019 saw the highest number of new protectionist measures adopted in ten years (1066 against 1049 in 2018 and only 284 in 2009). Receding multilateralism impaired the potential of coordination in the case of a major shock hitting the world economy

Pockets of resilience included savings and policy activism. Despite the high level of uncertainty, demand- and service-oriented activities were resilient in 2019. Gross domestic saving levels remained high: above 45% in China, close to 25% in the Eurozone and 15% in the U.S. Companies were still enjoying solid profitability: While margins had started edging downwards, they ended 2019 close to their long-term averages. Lastly, 2019 had also brought back policy activism, especially monetary policy easing, which helped cushion the blow of trade tensions.

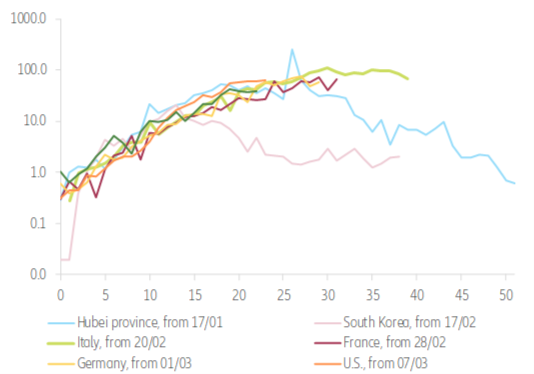

The coronavirus outbreak came as a black swan. At the time of writing, there were around 700,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide. The pandemic first appeared in the Hubei province of China in late-December 2019. Official responses started in earnest in mid-January, and the first confinement measures were put in place on 23 January 2020. From then, it took around one month for the spread of the virus to slow, and another month for the beginning of a gradual lifting of confinement measures. Up until 26 February, the epidemic was vastly concentrated in China (more than 95% of confirmed cases). It has since spread to the rest of the world, with, for e.g., more than 50% of cases located in Europe, as of 26 March. Confinement measures were put in place in Italy, Spain and France on 10, 14 and 17 March, respectively, i.e. between 1.5-2 months after China. Drawing from the Chinese experience, this means that the global pandemic could last until June at least.

Figure 1: Daily change in number of confirmed cases per 1mn people