Executive Summary

- Food prices and food security concerns were high on the agenda of the G7 group of countries meeting on 13-14 May in Stuttgart (Germany). Agricultural food prices rose by +31% in 2021 and will increase by a further +23% in 2022 amid a general increase in input costs (fuel, electricity, fertilizers), years of lower agricultural yields translating into low stocks and, more recently, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine impacting not only the supply of food staples such as wheat or oil, but also having ripple effects on the prices of substitutes.

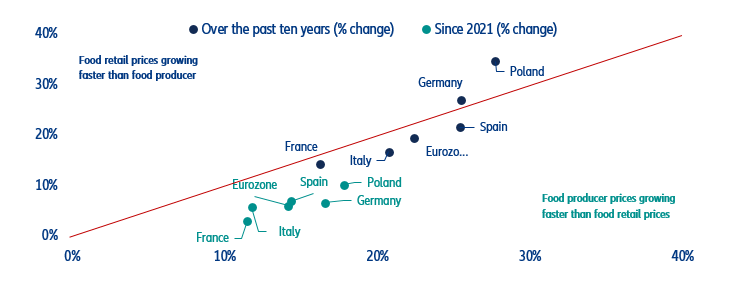

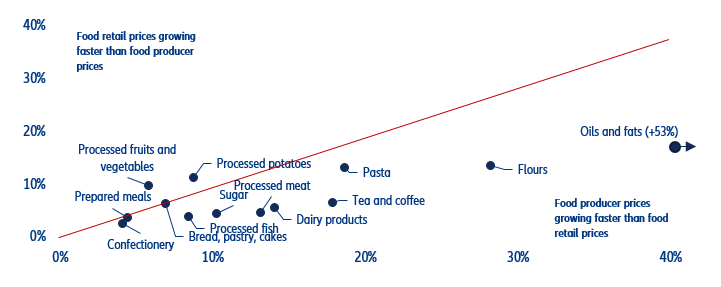

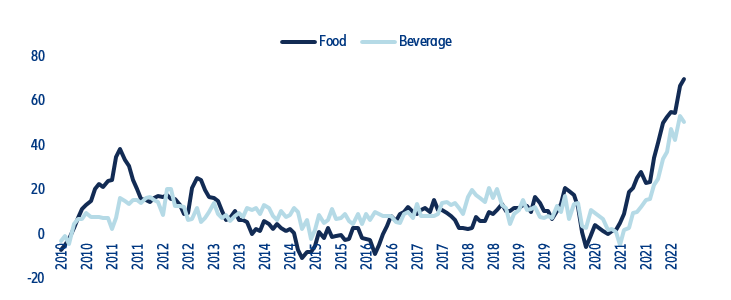

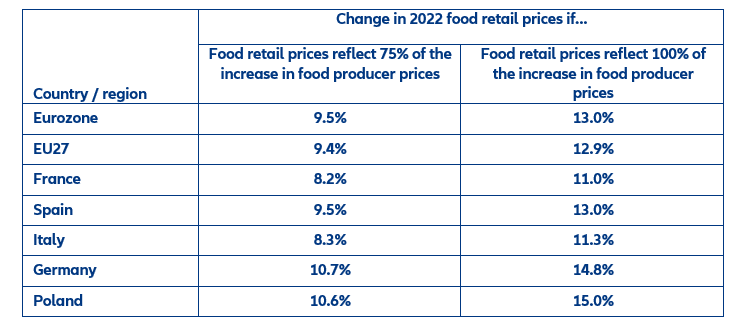

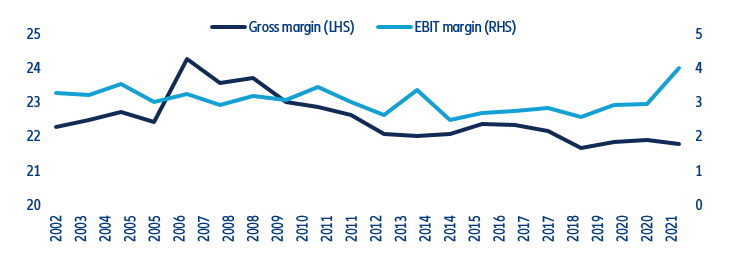

- The worst is yet to come for European households: Food retail prices are far from reflecting the surge in food commodity prices observed over the past 18 months. Eurozone food and beverage producers have already increased their prices by an average of +14% since the beginning of 2021, with the strongest price increases found among everyday life products, including oils and fats (+53%), flours (+28%) and pasta (+19%). In contrast, food retail prices have only adjusted by a modest +6%, meaning retailers have not yet passed on even half of the higher food producer prices onto food retail prices. But past episodes of high food inflation show that retail prices broadly adjust to producer prices with some lag. High inflation, together with a post-pandemic decline in food volume sales in stores, will add pressure to the profitability of European food retailers but we anticipate generally high pass-throughs to consumer prices.

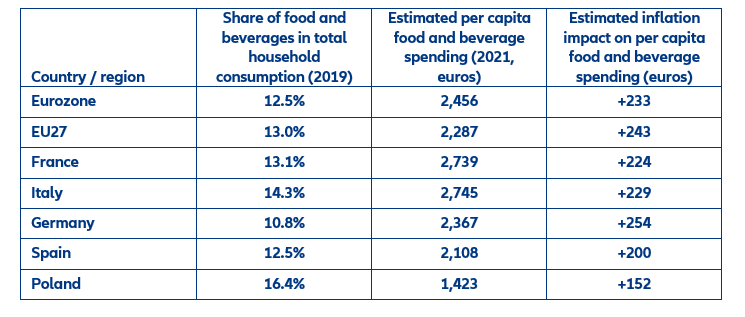

- Using our central estimate of retailers passing the equivalent of 75% of the past increase in food producer prices onto consumers, we compute that food inflation would cost the average European consumer an extra EUR243 for the same basket of food products vs 2021, with estimates ranging between EUR200 to EUR250 in Europe’s four largest consumer markets. Coming on top of a more general increase in the cost of living (fuel, electricity, rents, away-from-home food, etc.), this surge in food prices is likely to revive debates on possible welfare payments to relieve the burden for the most vulnerable households.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has added to a context of already high food commodity prices.

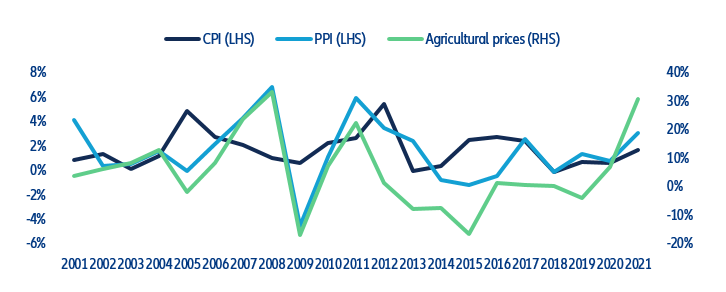

A mix of firm demand growth, higher input costs (fertilizer, electricity, freight rates) and years of lower yields sent agricultural food prices up +30.8% in 2021, bringing the index to levels last seen in 2012. Because price growth accelerated markedly in the second half of the year, European consumers only partially felt the pinch in 2021, with food producer prices up +3.1% and food consumer prices up +1.7% compared to 2020. While food producers and retailers were already expecting further food price inflation for 2022 at the beginning of the year, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine only added to fears of higher food inflation, given the countries’ significance in the agricultural commodity markets. With agricultural food prices now expected to grow another +22.9% in 2022, European consumers should brace for an unprecedented increase in food retail prices (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Eurozone food consumer prices, producer prices and international agricultural food prices (% change YoY)