EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

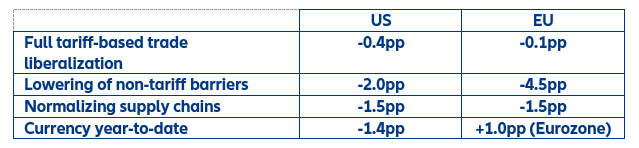

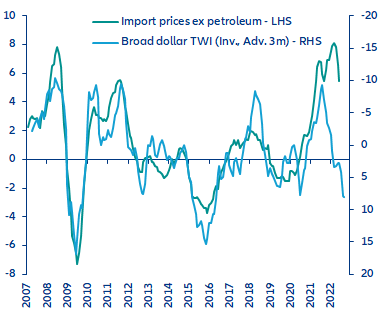

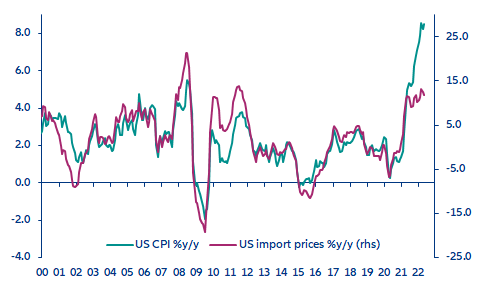

- A stronger US dollar will not be enough to rein in inflation in the US. Even as the appreciation of the USD will reduce inflation by -1.4pp in the next three months, and the US is less exposed to surging energy prices, we still expect inflation to remain well above 2% next year. In this context, the Biden Administration is considering lifting some of the tariffs imposed on China during the Trump era, and stepping up efforts to strengthen supply chains.

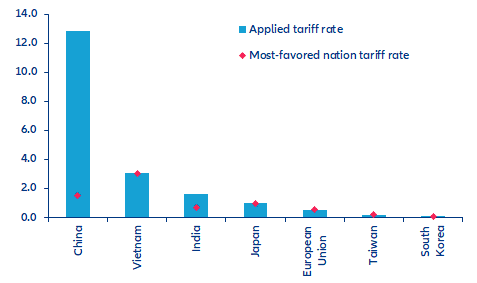

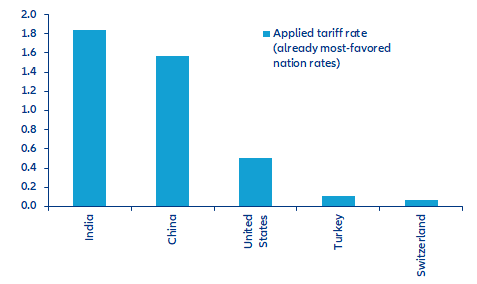

- However, we find that even a full tariff-based trade liberalization in the US and the EU would not be a game-changer for the inflation outlook. If tariff rates on the main import partners (including China) were shaved to zero, inflation would be reduced by just -0.4pp in the US and -0.1pp in the EU, given the high share of duty-free imports (72% in the US on non-agricultural goods, 56% in the EU) already in place.

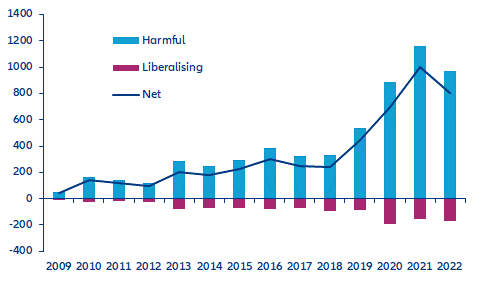

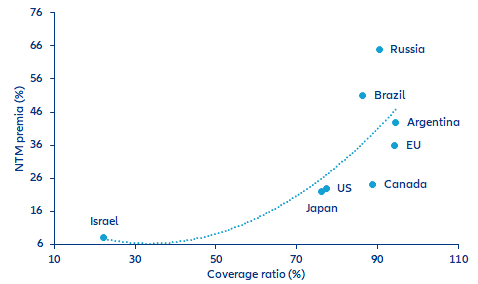

- In contrast, lowering non-tariff barriers to trade would have a material impact. In the US, close to 80% of trade is affected by non-tariff measures, while in the EU it is close to 95%. We find that reducing non-tariff measures to trade to below 50% would lower corporate markups and in turn knock at least -2pp off inflation in the US and -4.5pp in the EU. Lowering protection for local producers could thus yield sizeable benefits for consumers, especially in the EU, where the -9% depreciation of the EUR will push up inflation by more than +1.0pp after one year.

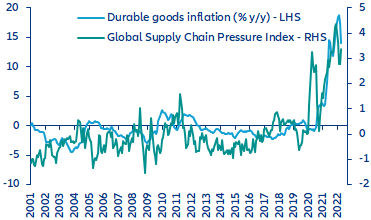

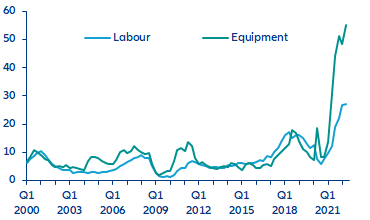

- Easing supply-chain disruptions could also lower inflation by up to -1.5pp in both the US and the EU, according to our estimates. This would require normalizing industrial output and trade flows among key import partners in a context where China is likely to maintain its zero-Covid policy through Q2 2023. Separately, domestic policies could help, such as an infrastructure plan focused on ports and/or increasing competition in the shipping industry, accompanied by appropriate labor market policies.

Table 1: Impact of trade-related policy measures on inflation