Executive Summary

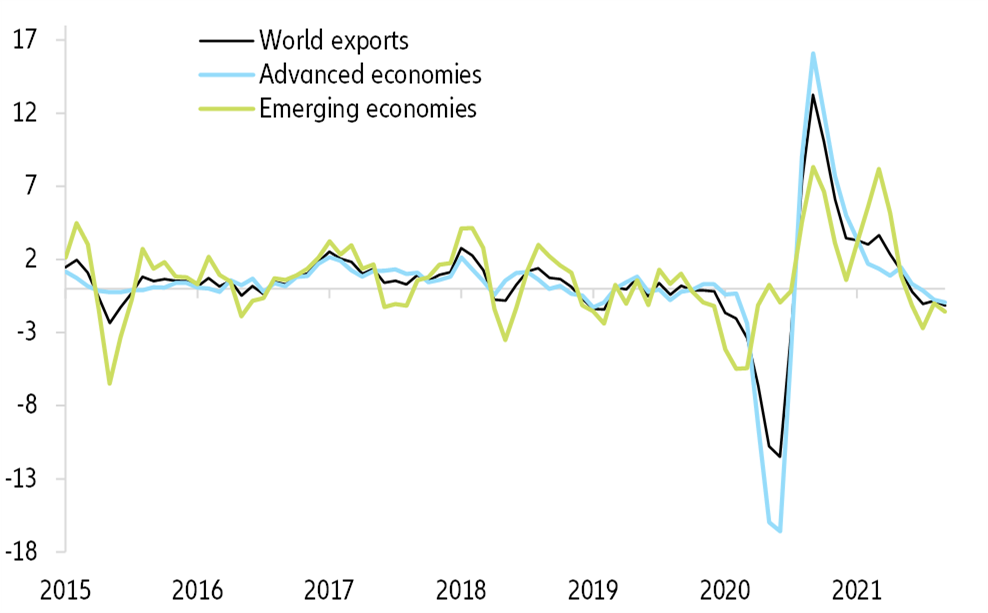

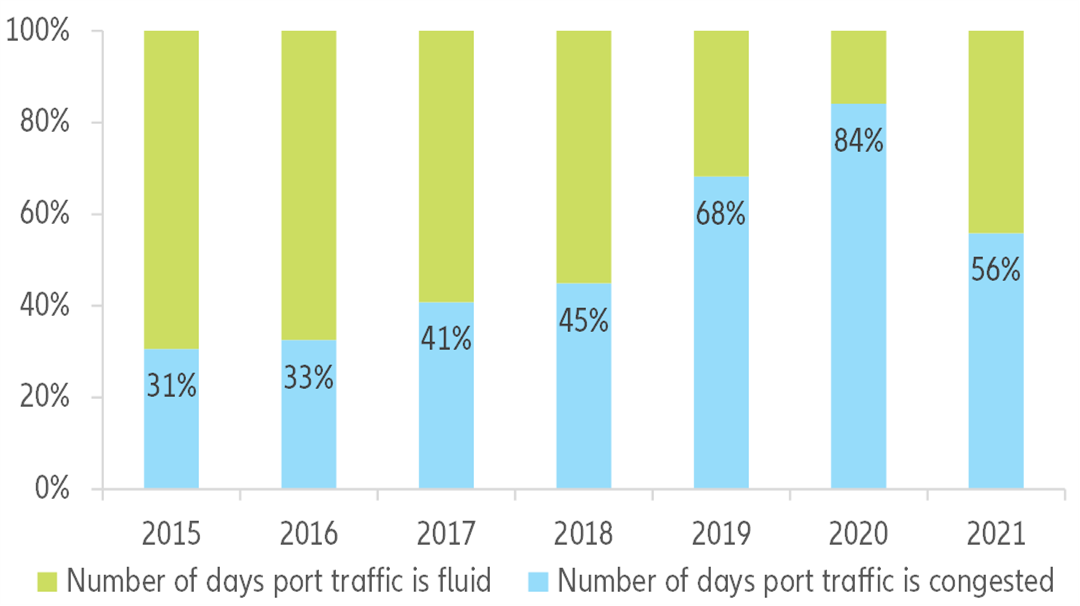

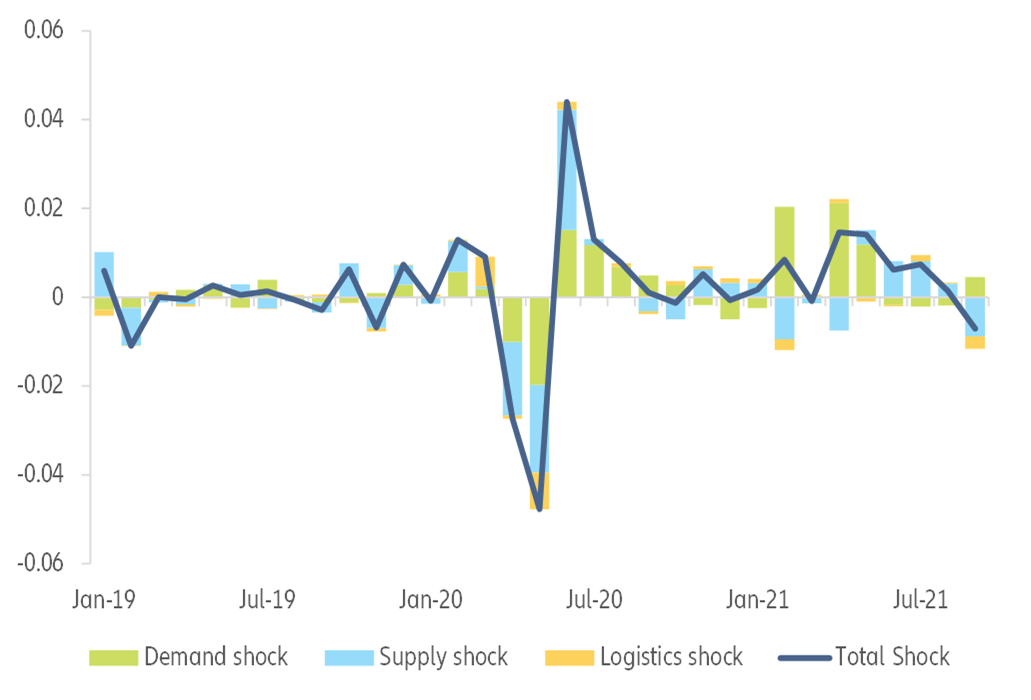

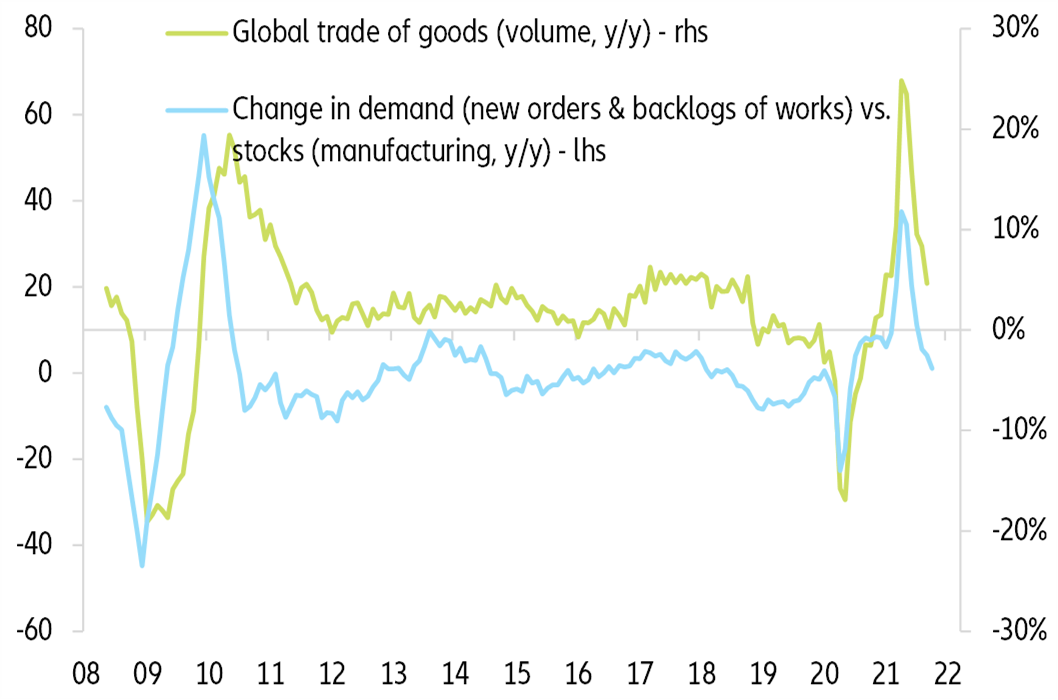

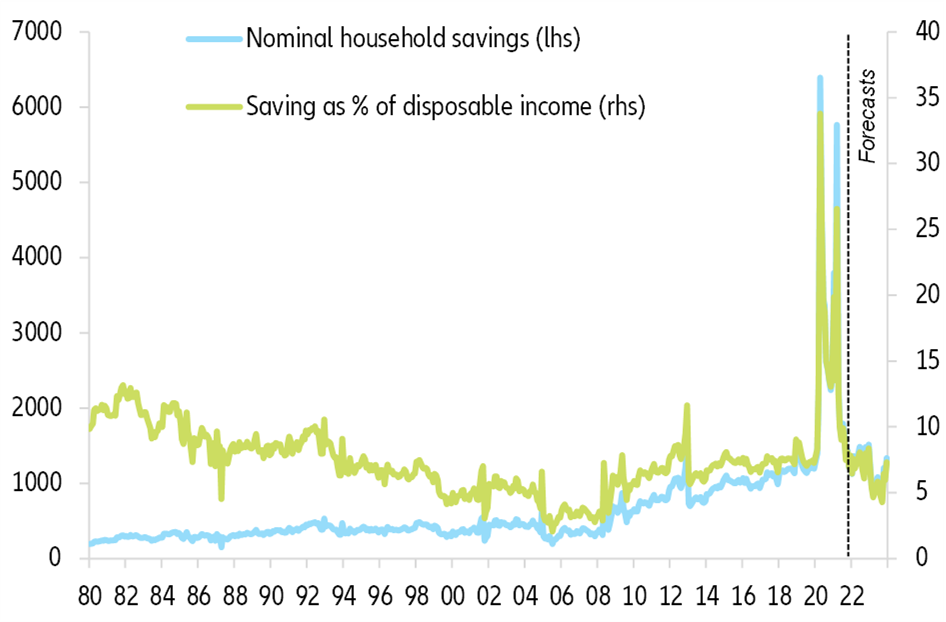

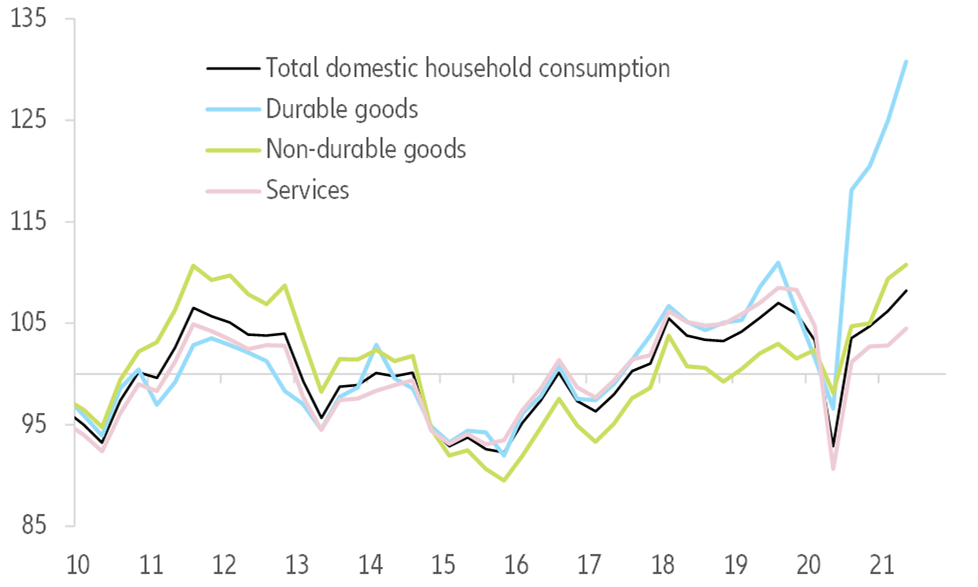

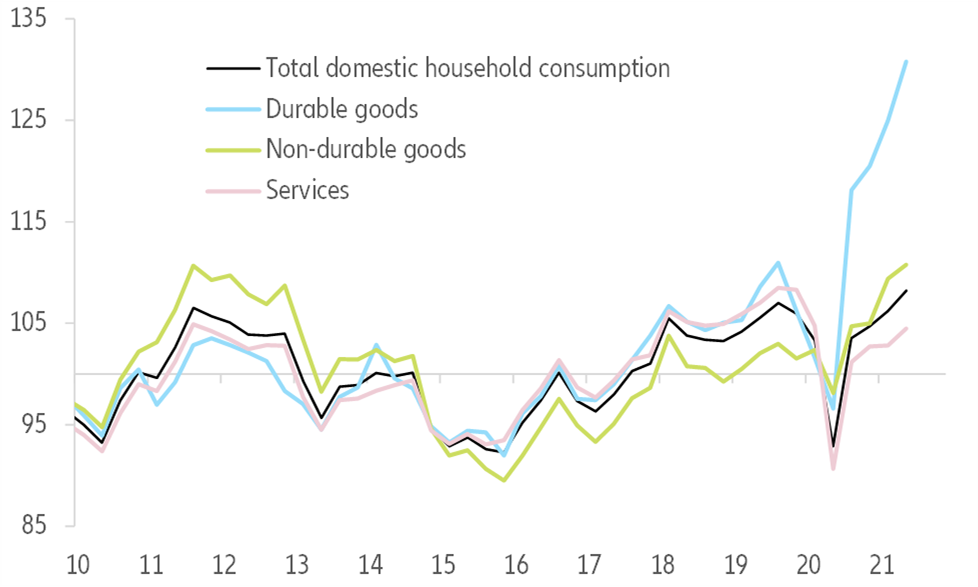

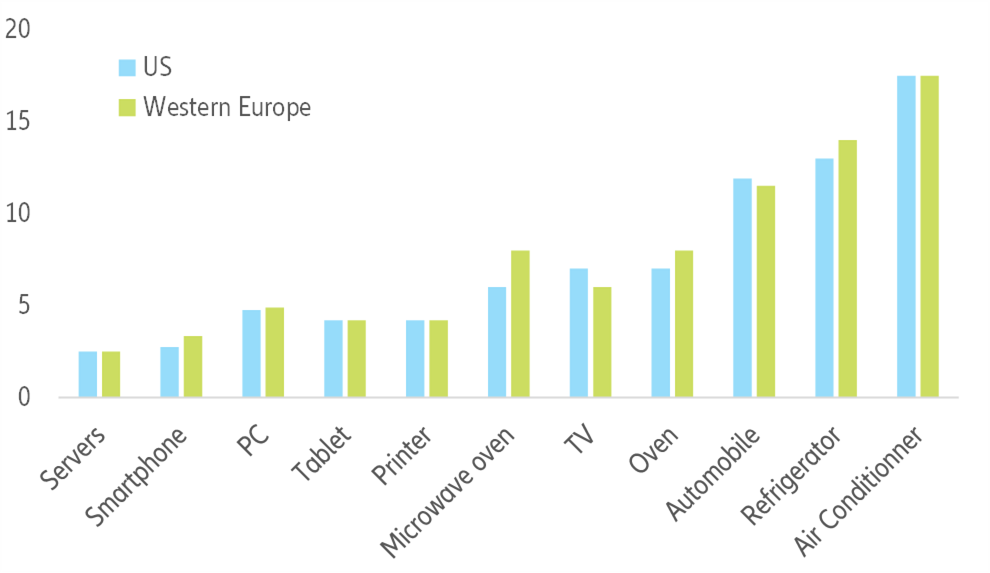

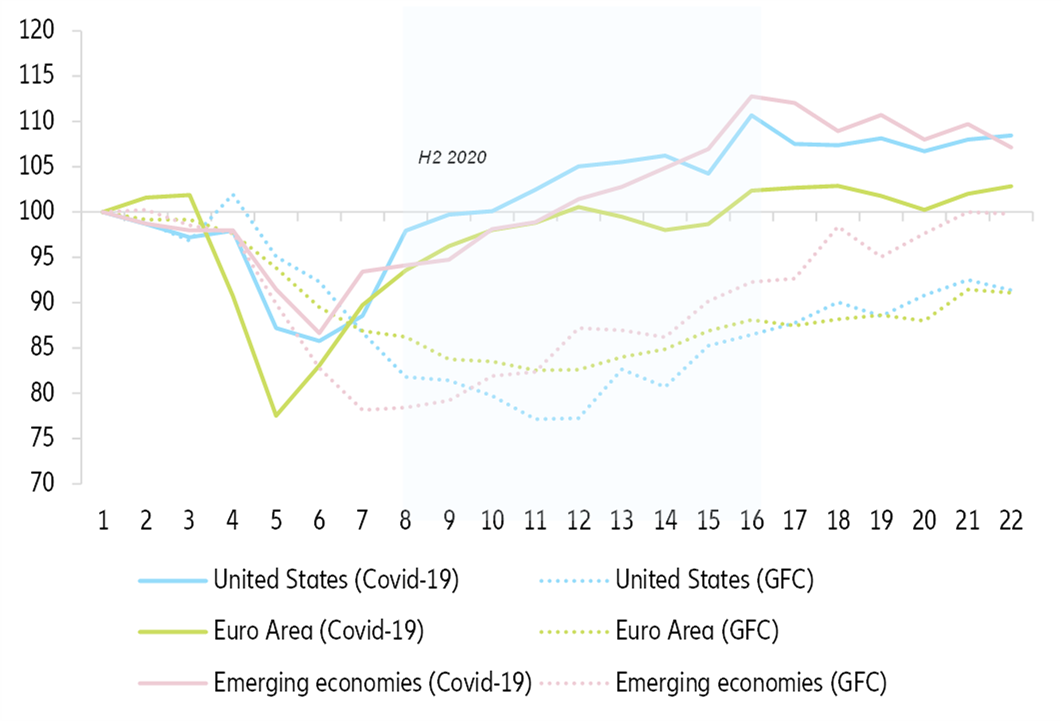

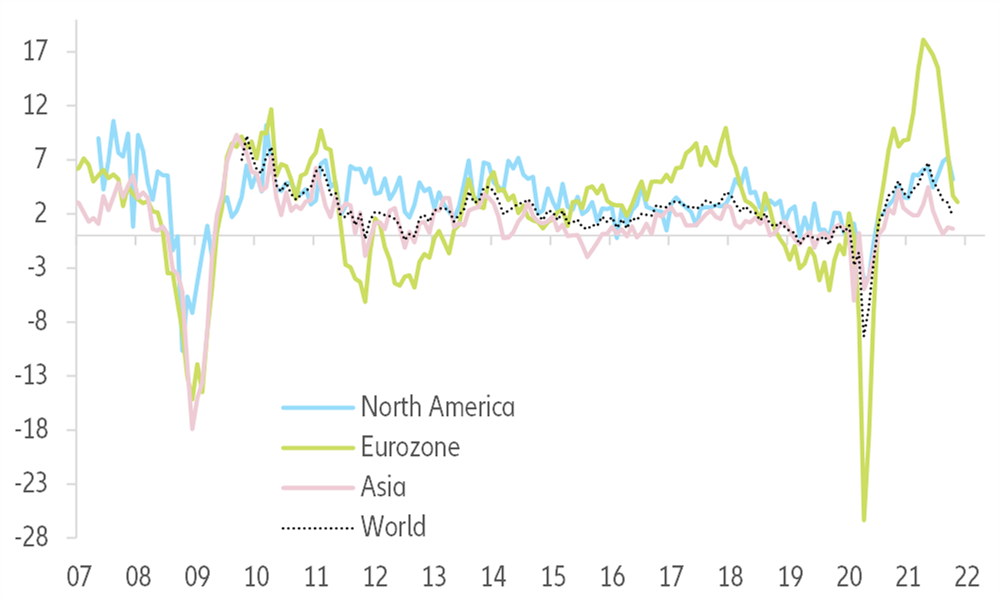

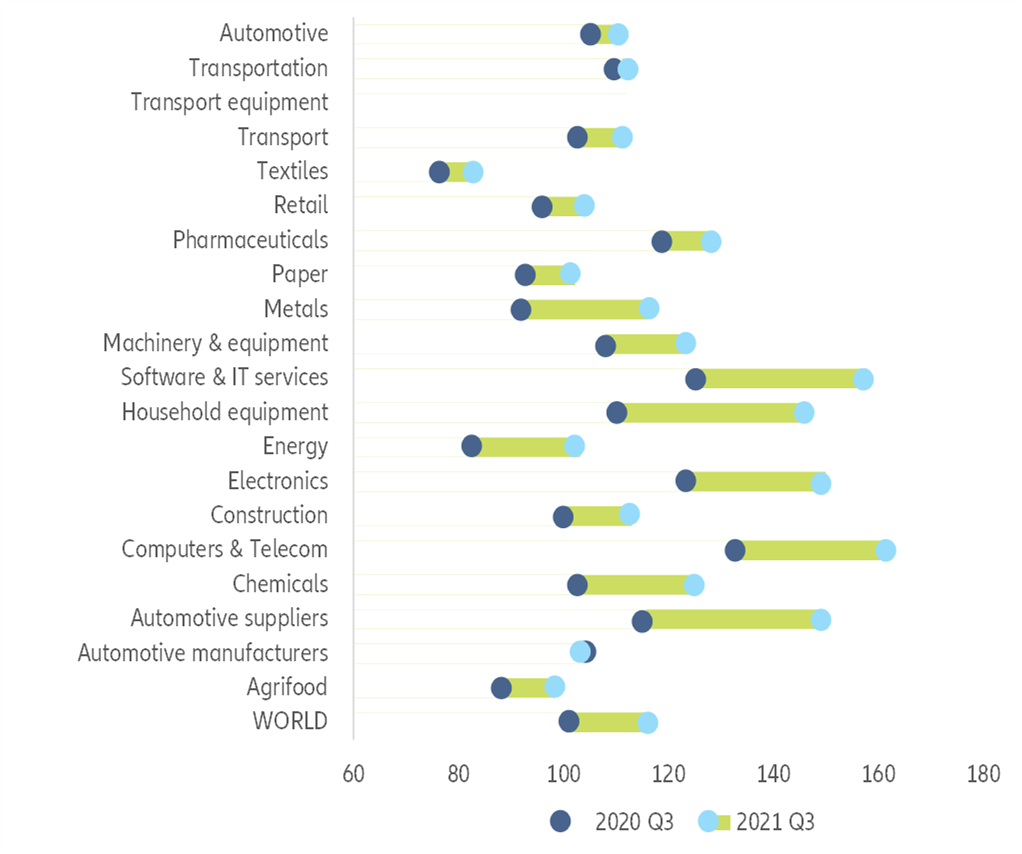

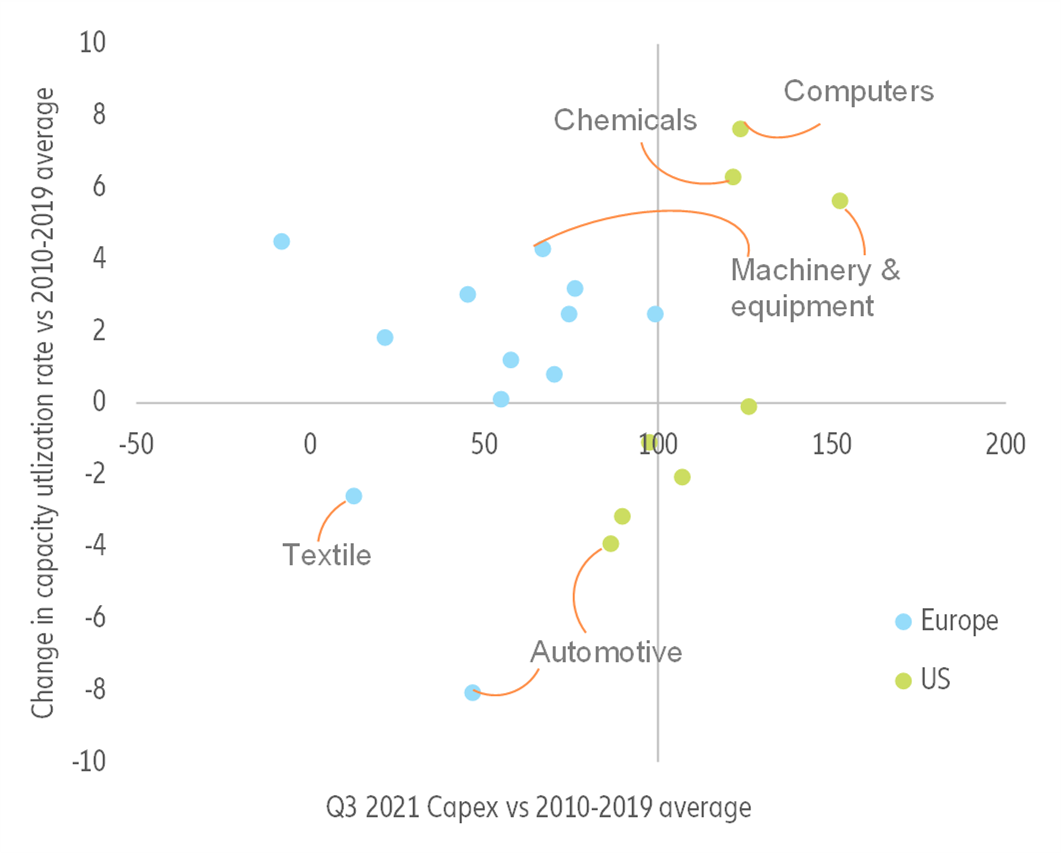

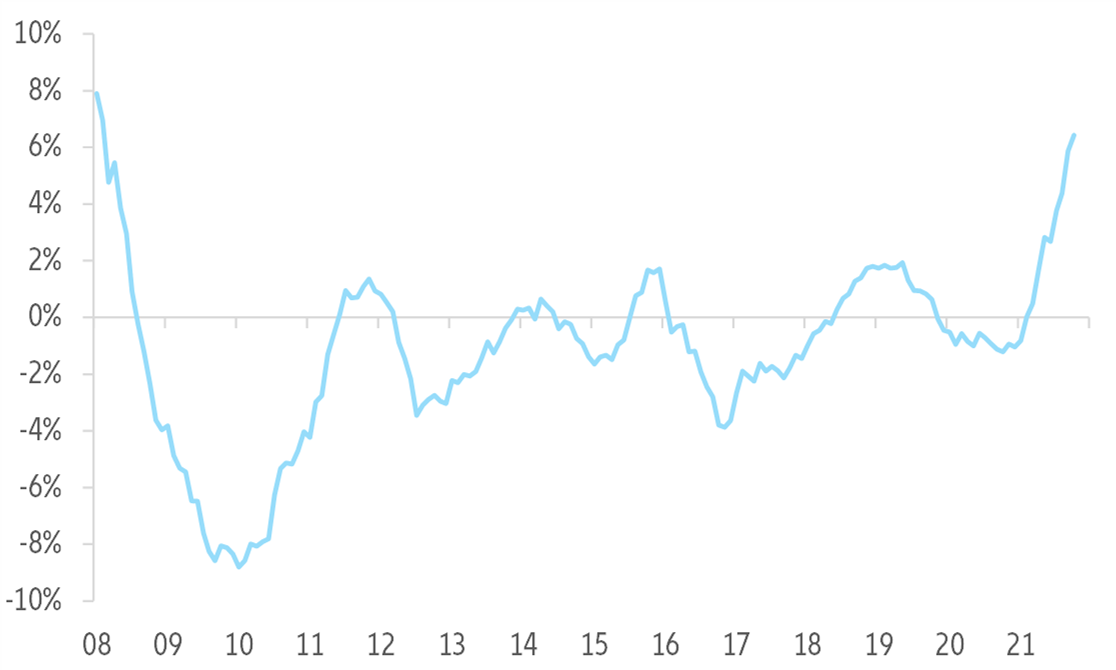

- Global supply-chain disruptions will remain high until H2 2022, on the back of renewed Covid-19 outbreaks globally, China’s continued zero-Covid policy and demand and logistic volatility during Chinese New Year. After exceptionally strong performance since H2 2020, global trade of goods contracted in Q3. We find that production shortfalls are behind 75% of the current contraction in the global volume of trade, with the rest explained by logistic bottlenecks. In this context, a soft recovery in Q4 2021 is likely (+0.8% q/q after -1.1% in Q3 for trade in goods) but there is a risk of a double-dip in Q1 2022 as volatility in trade flows should remain the norm until the spring. Looking ahead, three factors will drive the normalization of trade from H2 2022: 1) A cooling down of consumer spending on durable goods, given their longer replacement cycles and the shift towards sustainable consumption behaviors. 2) Less acute input shortages as inventories have returned to or even exceeded pre-crisis levels in most sectors and capex has increased (mainly in the US). 3) Reduced shipping congestions as capacity increases.

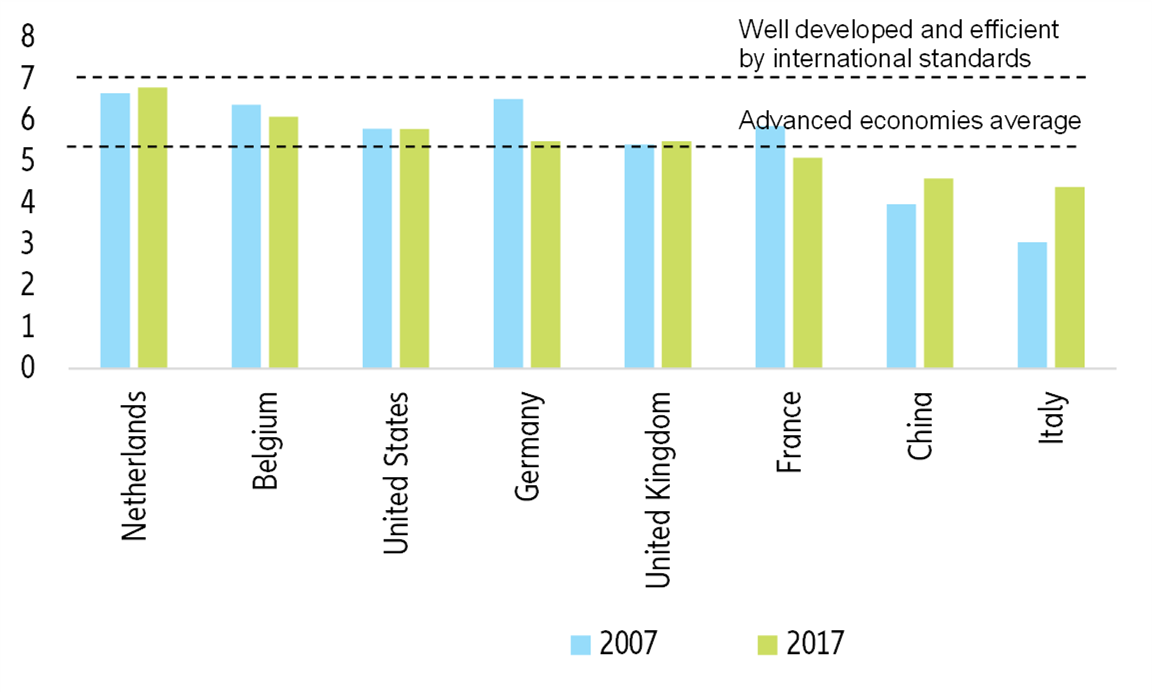

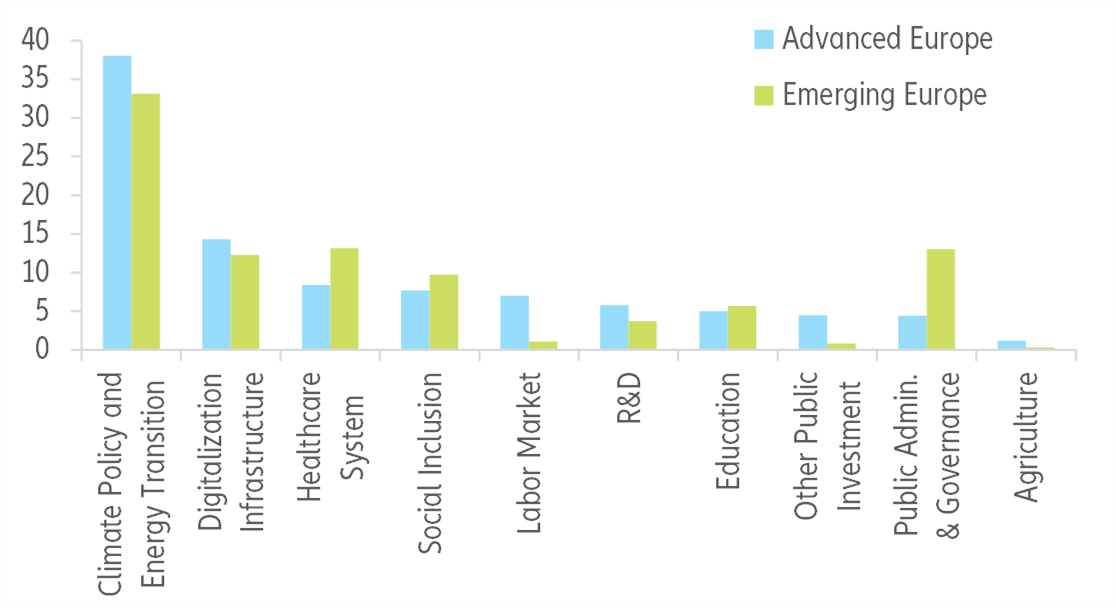

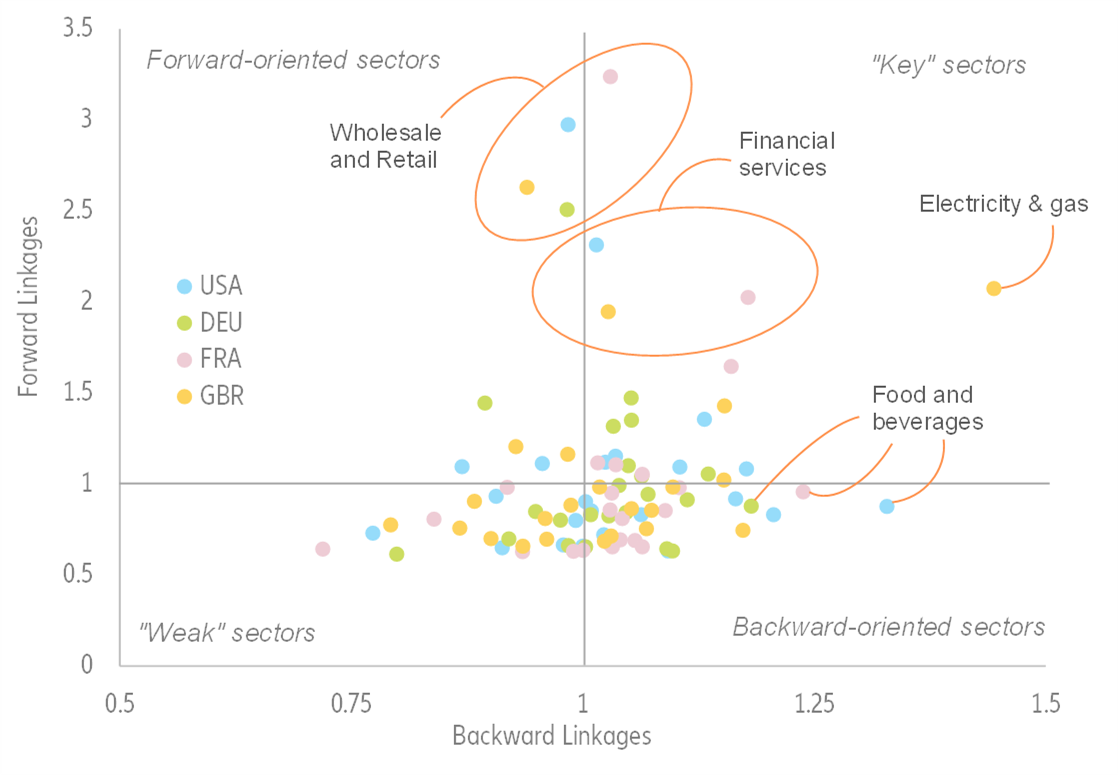

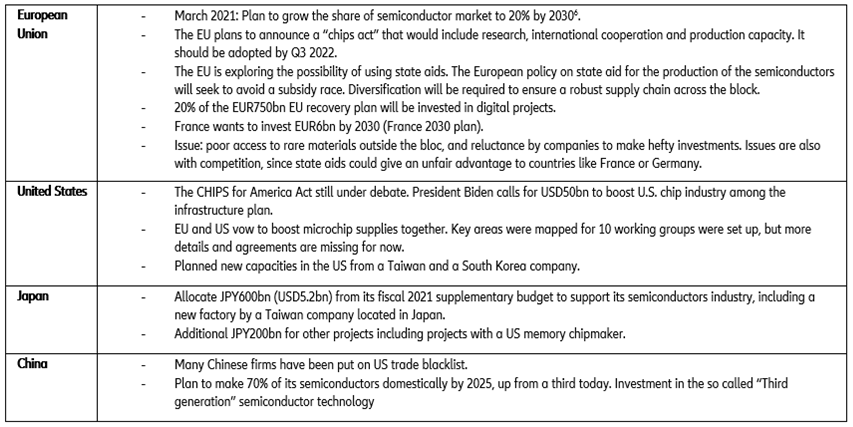

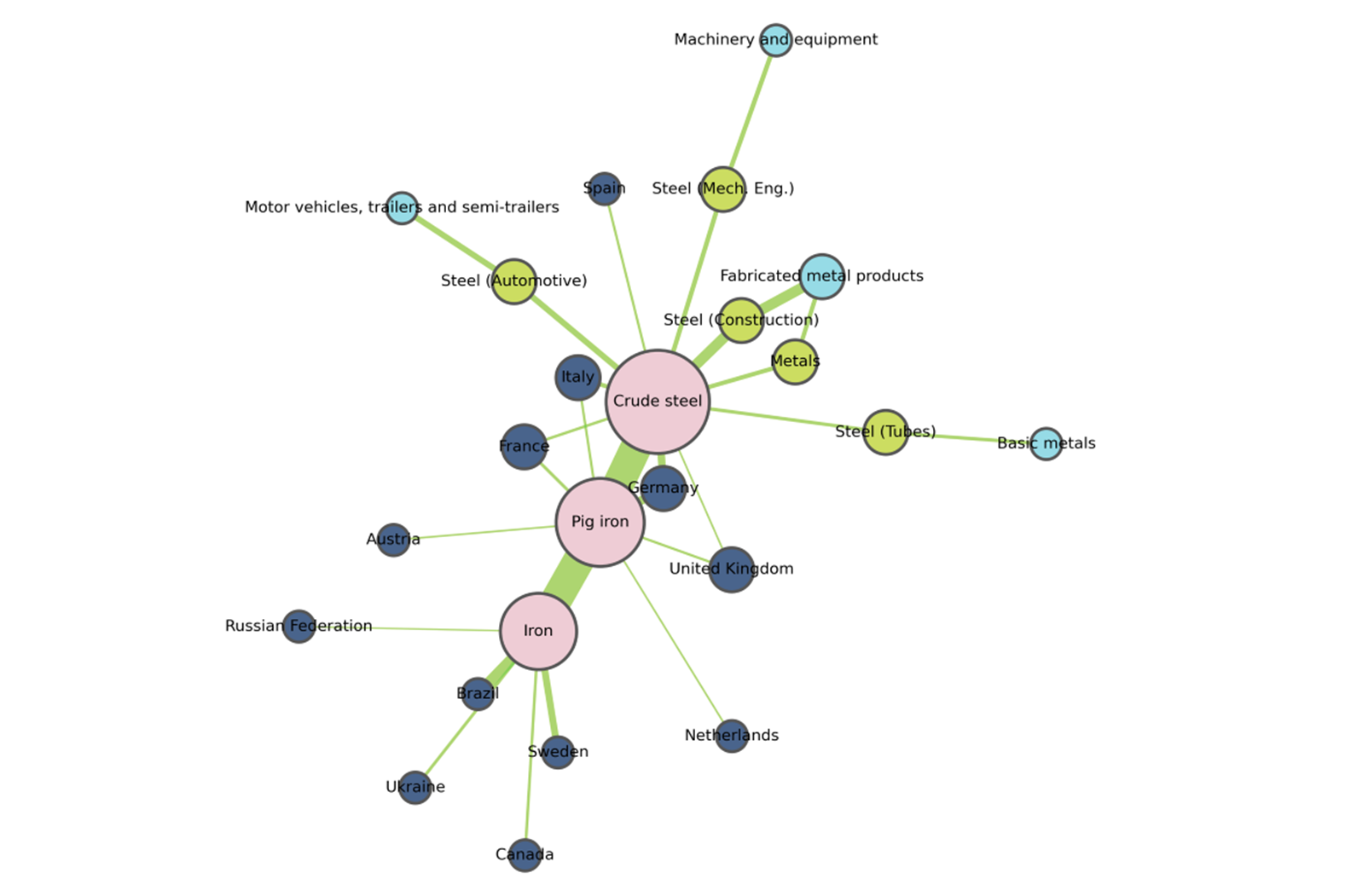

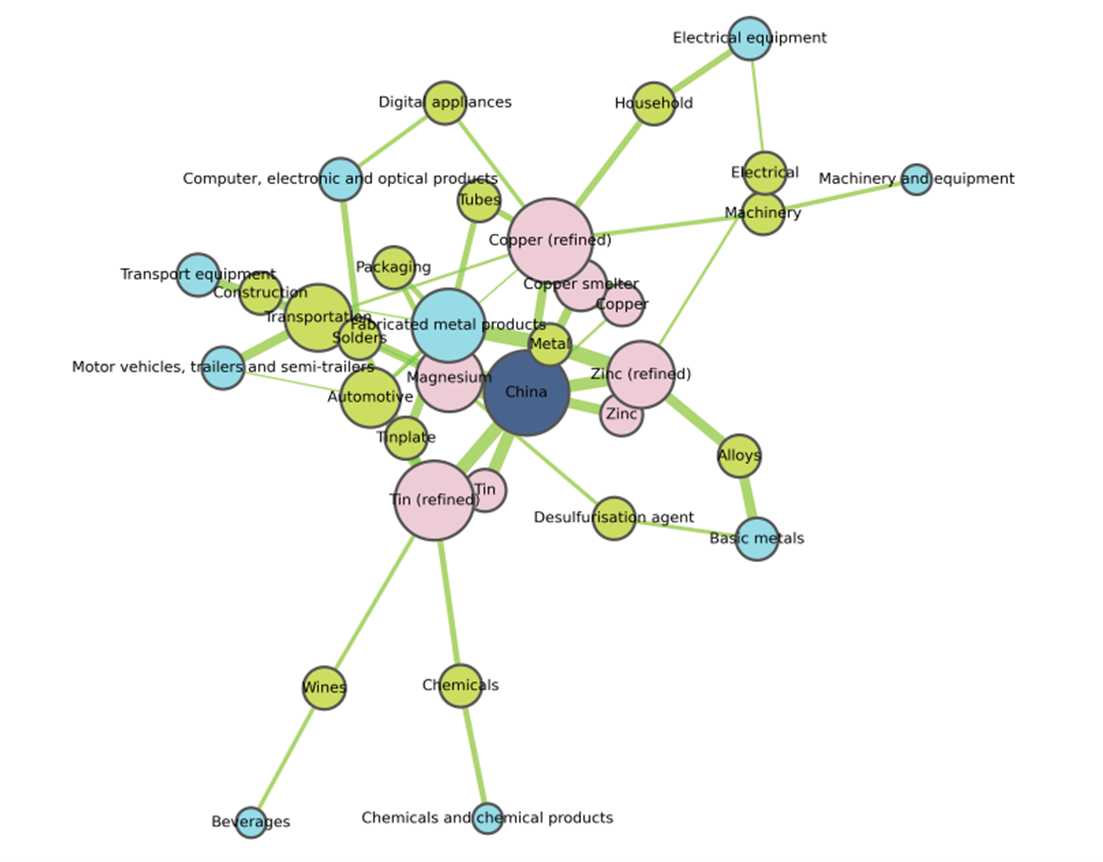

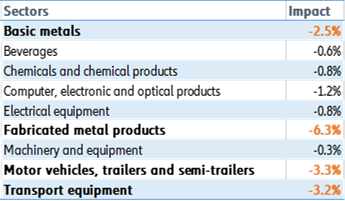

- When it comes to inputs from China, Europe is on the weak side of the tug-of-war against the US. Europe is more at risk compared to the US when it comes to the heavy reliance on intermediate inputs from abroad, due to a lack of capex in production and shipping capacities. We simulate the impact of a shock represented by the Chinese slowdown (i.e. a 10% drop in Chinese exports) on EU sector outputs and find that the sectors that would be hit the hardest are the ones related to metals (basic metals and fabricated metal products) and automotive (motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers, transport equipment). Without production capacity increases and investments in port infrastructure, the normalization of supply bottlenecks in Europe could be delayed beyond 2022 as demand remains above potential.

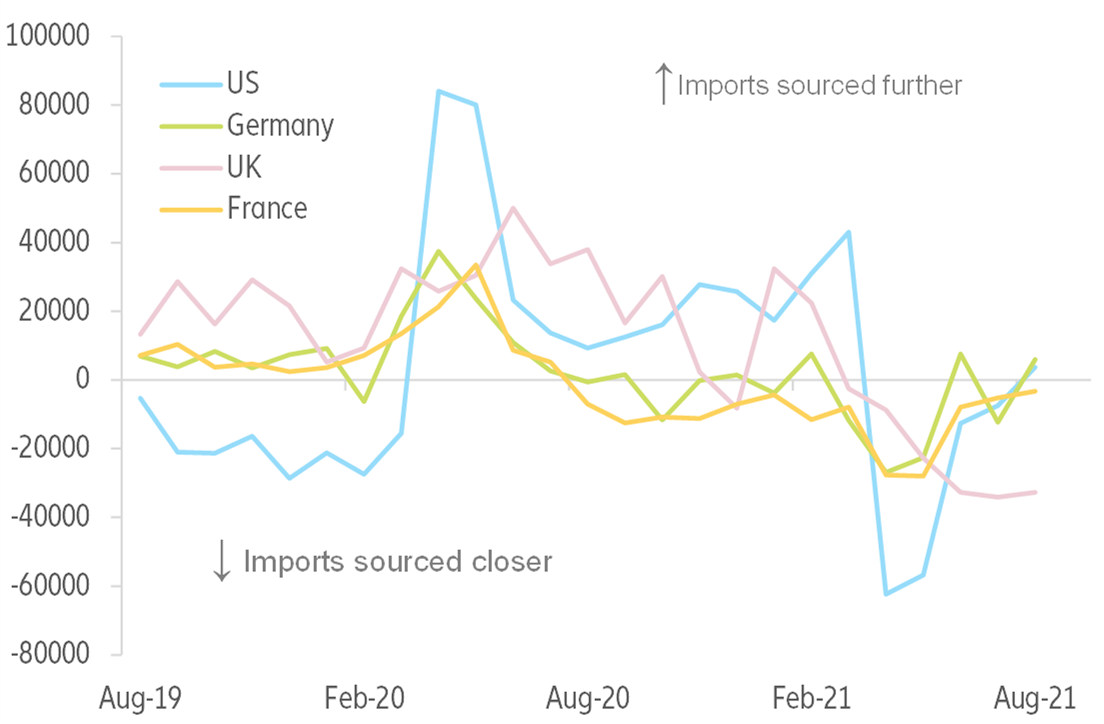

- Yet, reshoring and nearshoring will remain more talk than walk. Despite supply-chain disruptions, we find no clear trend of reshoring or nearshoring of industrial activities so far. The only exception is the UK, which is likely to have faced disruptions due to Brexit. However, protectionism reached a record high in 2021 and should remain elevated, mainly in the form of non-tariff trade barriers (e.g. subsidies, industrial policies).

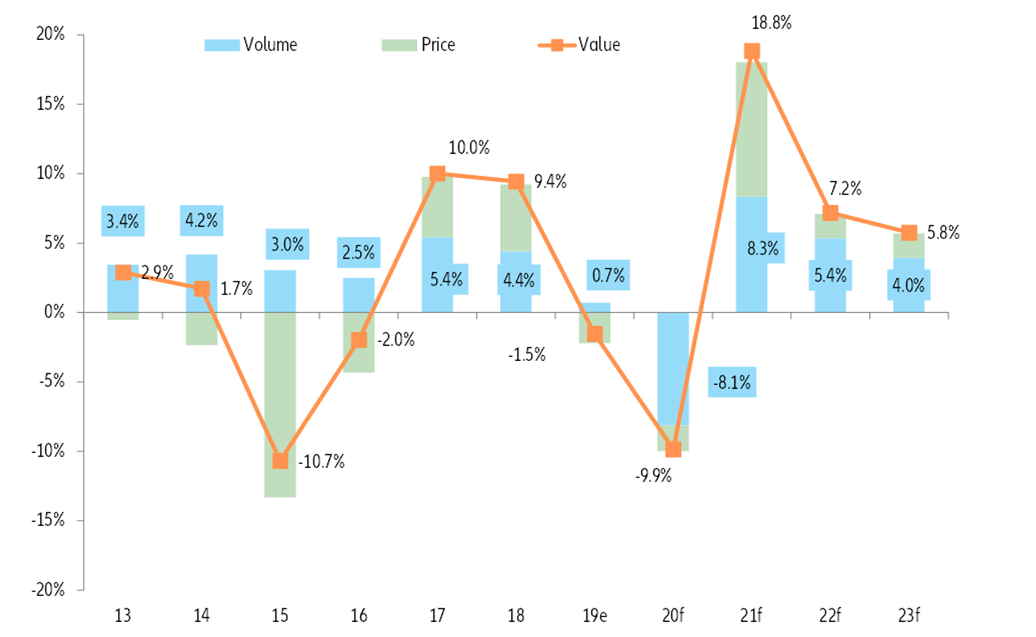

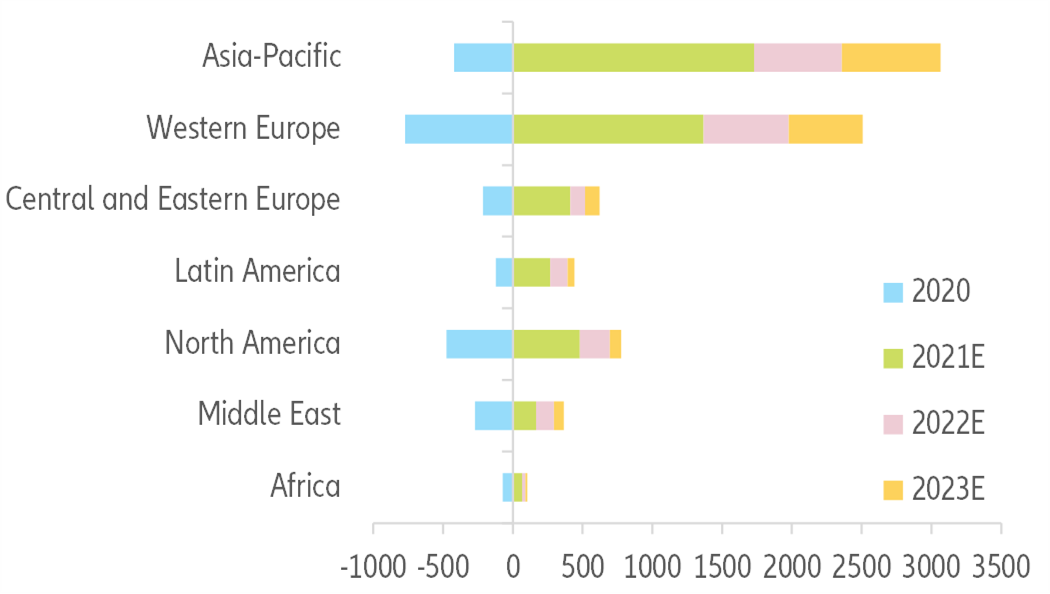

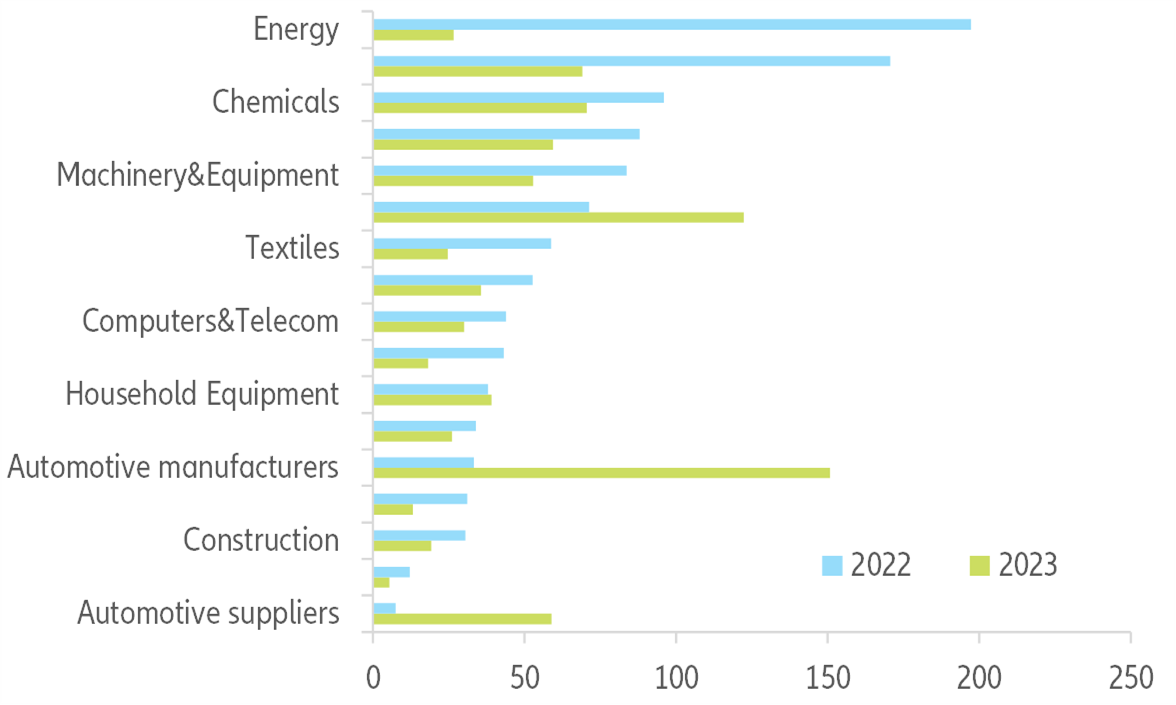

- Overall, we expect global trade in volume to grow by +5.4% in 2022 and +4.0% in 2023, after +8.3% in 2021. But watch out for increased global imbalances: The US will register record-high trade deficits (around USD1.3trn in 2022-2023), mirrored by a record-high trade surplus in China (USD760bn on average). Meanwhile the Eurozone will also see a higher-than-average surplus of around USD330bn. In terms of export gains, Asia-Pacific should continue to be the main winner in the next few years (over USD3trn in 2021-2023). By sector, energy, electronics and machinery & equipment should continue to outperform in 2022, but the main export winner globally in 2023 should be automotive, thanks to the backlog of work and lower capex in 2021.