EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

After an election campaign dominated by the topics of dwindling purchasing power and surging energy prices, it is now time for an economic reality check in France. The first 100 days of Macron’s second term need to establish a roadmap to tackle three issues in urgent need of reforms.

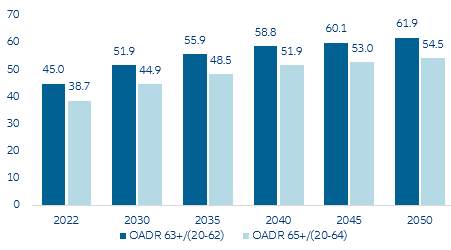

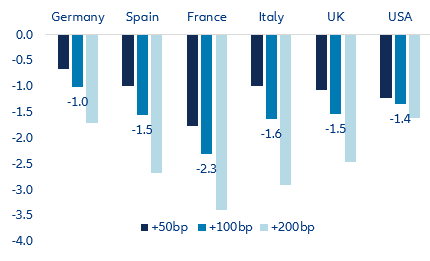

- France’s deteriorated fiscal position and mounting public debt. As the ECB sets the stage for tighter monetary policy, we estimate that 100bp increase in the key interest rate would raise France’s debt-service cost by more than EUR30bn over 10 years (1.5% of GDP). In this context, pension reform needs to be quickly put back on the table: We estimate that increasing the retirement age by two years could reduce public pension spending by almost 2% of GDP per year, equivalent to around EUR40bn, which could be harnessed to spur sustainable growth and accelerate the green transition.

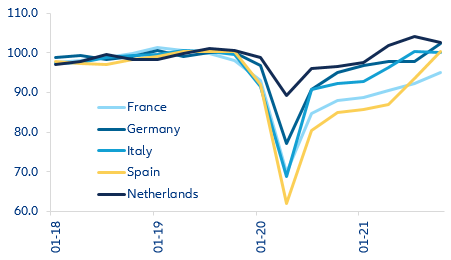

- Record-high corporate debt alongside above-trend household savings. We estimate that non-financial corporates’ margins need to increase by +1.5pp on average in order to absorb the remaining +8.7pp increase in the corporate debt-GDP ratio since the outbreak of Covid-19. However, margins are likely to fall by -2.3pp by mid-2023. At the same time, French households hold close to EUR250bn in excess cash compared to pre-Covid times, which should be increasingly directed towards long-term investments (decarbonization, digitalization, corporates’ productive investments) rather than the housing market.

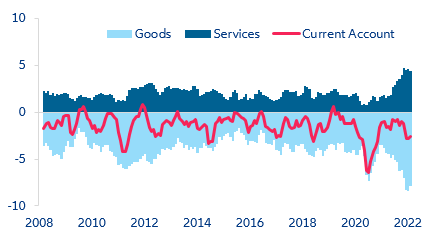

- Increased external imbalances amid a widening trade deficit and growing reliance on financing from the rest of the world. France clearly underperforms its Eurozone peers when it comes to export performance and is highly exposed to supply-chain disruptions and shortages. The war in Ukraine has highlighted the urgency of achieving energy independence and speeding up the development of non-fossil energy sources, as well as re-thinking sectorial specialization. France’s energy deficit could reach EUR75bn in 2022, or 2.9% of GDP (vs. 1.9% of GDP in 2019). In this context, it needs a clear roadmap to revise its industrial policy and upsize its manufacturing capacity via increased reliance on digital technologies, automated manufacturing and machining processes and clean energy sources.

Pension reform could put France’s public debt trajectory back on track.

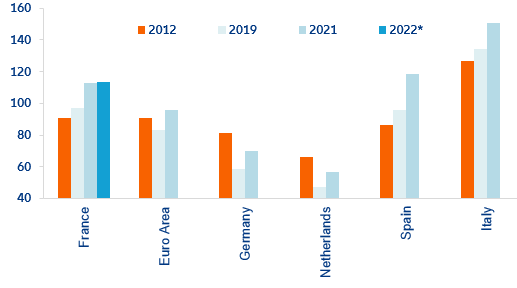

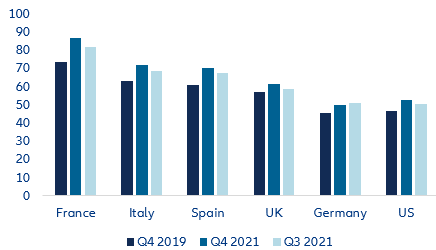

Public debt has been rising in France over the past decades, placing the country in a semi-core position within the Eurozone. In contrast to the core economies (e.g. Germany, Austria, the Netherlands), France’s public debt grew between 2012 and 2019, as it did in Italy and Spain.

This was followed by a “whatever it costs” approach in response to the Covid-19 crisis, which generated EUR325bn of additional debt. The direct debt induced by the Covid-19 crisis is estimated at EUR165bn while the indirect debt (i.e. tax revenues foregone) reached around EUR160bn. Consequently, French public debt increased by +18.7pp of GDP between 2019 and 2021 to reach 113% of GDP (versus 96% in the Eurozone overall). France’s debt-to-GDP ratio is currently the fifth-highest in the EU, 43pp above that of Germany. In 2022, we expect public debt to hover around 113.5% of GDP without a significant reduction in the context of the presidential elections and sustained costly public support measures (above EUR20bn) to curb energy prices.

The large and recurrent primary deficit could also increase debt-sustainability issues. France’s budget deficit as a percentage of GDP has been on an increasing trend since the outbreak of Covid-19, worsening from crisis to crisis and never returning to its initial level. On average, France’s fiscal policy has been more expansionary than that of its Eurozone peers during and after the pandemic. Since the last Eurozone crisis and prior to 2020, France registered a primary deficit of -1.7% against +0.2% for the Eurozone. And France didn’t manage to post a primary surplus since 2001 compared to 11 years over the same period for the Eurozone. As a side effect of the continued “whatever it costs” response, the budget deficit widened dramatically to -8.9% of GDP in 2020 and -6.5% in 2021, after 3.1% of GDP in 2019.

At the same time, after a few exceptional years due to the Covid-19 crisis and the war in Ukraine, the EU’s fiscal rules will start to bite again in 2023. The French Court of Auditors finds that bringing the budget deficit in line with the current Maastricht criteria (i.e. below 3% of GDP) by 2027 would require EUR9bn in additional public savings each year compared to the trajectory observed between 2010 and 2019.

Figure 1: Government debt to GDP (%)