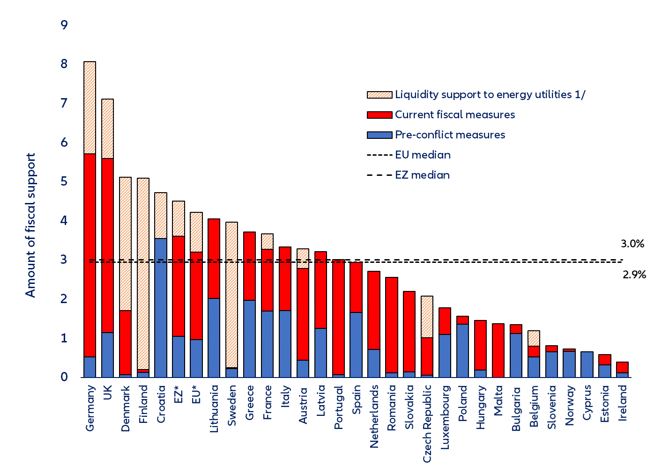

- We estimate that current (median) fiscal support amounts to about 3% of GDP in Europe (more than EUR475bn, on top of the EUR170bn pre-conflict). Unsurprisingly, the fiscal response is somewhat higher in countries with a larger energy-intensive industry and/or greater gas dependence. In most countries, the total measures (e.g. price caps, energy tax cuts, liquidity and equity injections, state-guaranteed loans, and furlough schemes) amount to around half of the Covid-19 packages. With the energy crisis – and in turn the inflation hit to the private sector – not yet past the peak, we expect EU governments to increase spending further. However, the big fiscal leaps are behind us as the room for maneuver is much more constrained amid rising interest rates.

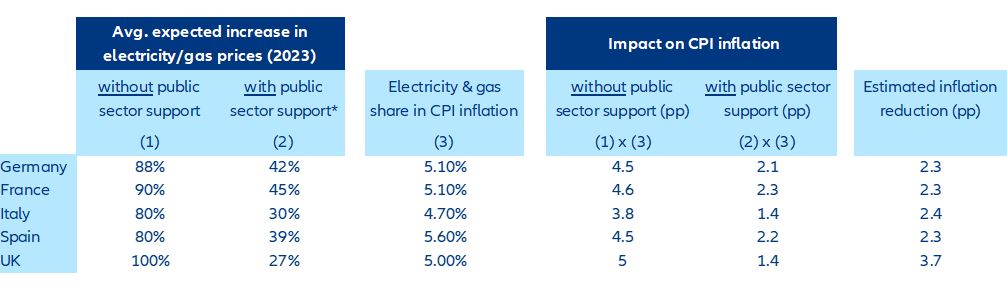

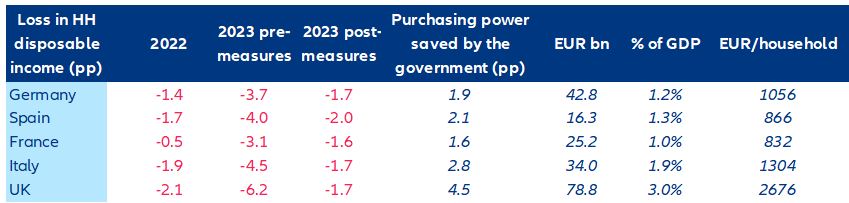

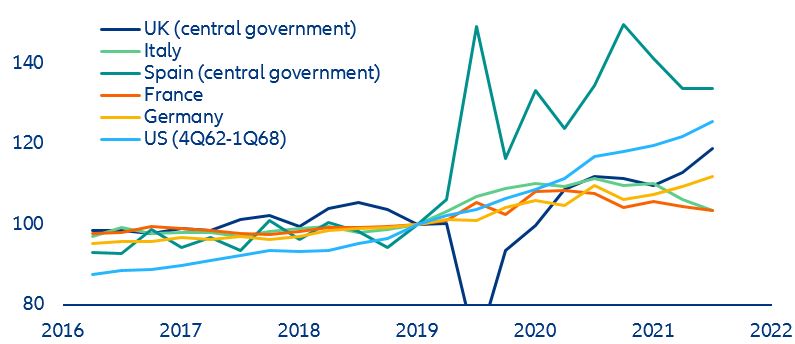

- Available fiscal support will reduce the impact of higher energy prices on real disposable incomes and soften the blow on demand but can also slow down the reduction in inflation rates overall. We estimate that current measures directly reduce inflation rates by lowering energy prices most in the UK (-3.7pp in 2023), followed by more than -2pp in Germany, France, Italy and Spain. By doing so, however, they “free” 1.7% of GDP of domestic demand on average, as the decline of household disposable incomes in 2023 will be more than halved from -4.3pp to -1.7pp on average (more than EUR1,300 per household). Based on the current trend of real government expenditures (above pre-pandemic levels in Spain, the UK and to a lower extent Germany, and back to pre-pandemic in France and Italy) and current fiscal plans, limiting the fall in aggregate demand will delay the pullback in inflation. However, a rise in the savings rate could mitigate the inflationary effects of these fiscal measures. We expect Eurozone and UK inflation to come in at 5.6% and 7.5%, respectively, in 2023 still way above the historical average.

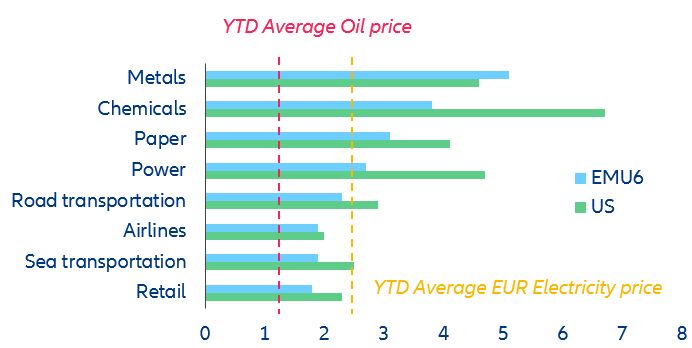

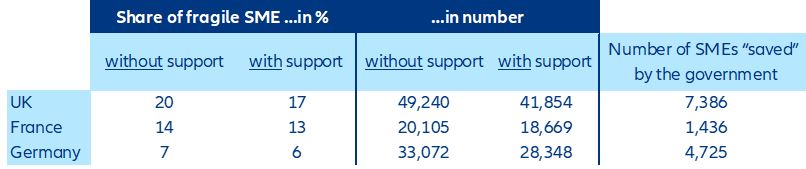

- Fiscal support measures should help limit the number of vulnerable firms becoming insolvent over the next four years. At current levels, energy prices would virtually wipe out the profits of most non-financial corporates as pricing power is diminishing amid slowing demand. If firms can pass one quarter of energy-price increases to customers, they can withstand a price increase of below +50% and +40% in Germany and France, respectively. Given the nature of the current crisis, governments chose to use more cash-based measures to offset the war-induced rise in energy prices. Indeed, for both political and economic reasons (high corporate leverage amid an environment of rising interest rates), promoting corporate leverage to face the crisis could prove to be a policy mistake. Thus, even weaker firms can survive: The share of fragile firms in the UK, France and Germany is stabilized at respectively 17% of total, 13% and 6%, or close to 42,000 firms in the UK, 28,400 in Germany and more than 18,700 in France. This means that on average governments will “save” more than 4,500 SMEs. However, as measures only offset much stronger rises in costs, they will not provide any additional boost to corporate profitability.

- The optimal policy response to the energy crisis would have been a swift structural overhaul of the European energy market. Since precious time was lost, the EU and national governments now need to resort to second-best options based on an EU Commission menu of policy options. Some key considerations are: 1) Fiscal support measures at the national level should not fuel EU divergence, including by distorting intra-European competition. 2) In cases where fiscal space is limited, joint borrowing could and should allow all EU member states to formulate an adequate fiscal response without putting additional strain on national budgets. However, fiscal support needs to be temporary and targeted. 3) Sustained energy-demand reduction will be inevitable in what shapes up to be a more persistent energy-supply crisis. Countries need to find a way to reduce gas consumption beyond near-term savings (which currently stand at only 10%). Retaining the signaling function of market-based prices plays a crucial role in sustainable self-rationing while facilitating efficient reallocation of energy demand.

Current measures - so far so good?

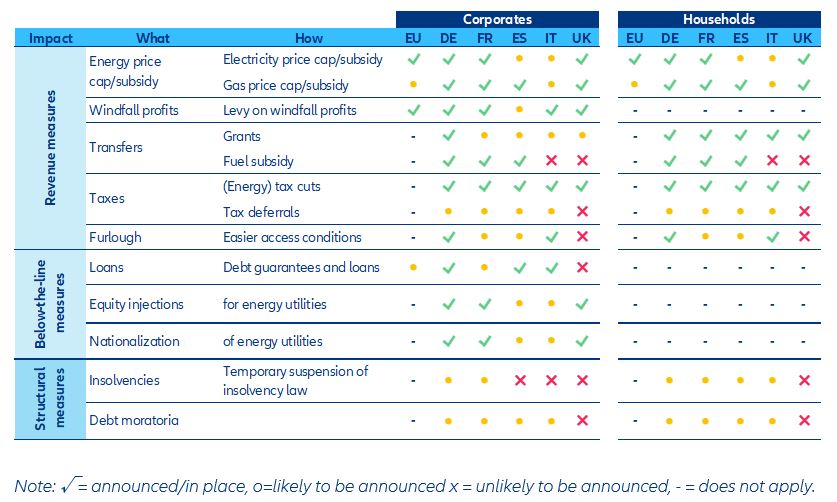

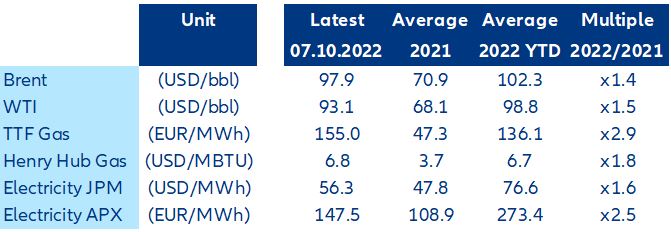

Governments have significantly scaled up their response to the energy crisis over recent months to mitigate the impact on vulnerable households and firms. Initially, support measures largely came in the form of limited needs-based government transfers (e.g. energy vouchers) and lower (energy) taxes in most countries, with the exception of France, and later on Spain, which imposed general price caps on electricity and gas, respectively (Figure 1). Most governments roughly doubled their support since the summer as energy prices continued to increase amid escalating sanctions on Russian energy exports and dwindling gas supply through Germany’s North Stream 1 pipeline (Figure 2). We estimate the median fiscal shield at about 3% of Western Europe GDP (more than EUR475bn on top of the EUR170bn pre-conflict), which includes both revenue and below-the-line measures, including public debt guarantees and credit lines to energy utilities. With the energy crisis – and in turn the inflation hit to the private sector – not yet past the peak, we expect EU governments to increase spending further. However, the big fiscal leaps are behind us as the room for maneuver is much more constrained amid rising interest rates.

The most significant national measure so far has been Germany’s massive EUR200bn economic “shield” to support industry and households amid the energy crisis. On 29 September, the German government unveiled plans for a "protective shield" for which up to EUR 200bn (5.6% of GDP) have been earmarked to subsidize above all a “basic amount” of electricity and gas and to reduce the VAT on gas and district heating to 7% until spring 2024. While the exact cost will depend on specifications that still need to be decided over the coming weeks, the total cost of the gas price subsidy amounts to EUR96bn (2.7% of GDP). In addition, the government decided to abandon controversial plans for a levy on household gas bills, which was supposed to start in October to partly fund the bailout of some utility companies as the government is in the process of nationalizing several of the most hit utilities. These costs will now have to be borne fully by the government.

One day later, the EU energy ministers reached a political agreement on the following measures to mitigate high electricity prices:

- Electricity demand reduction. A voluntary target of 10% of gross electricity consumption and a mandatory reduction target of 5% of electricity consumption in peak hours.

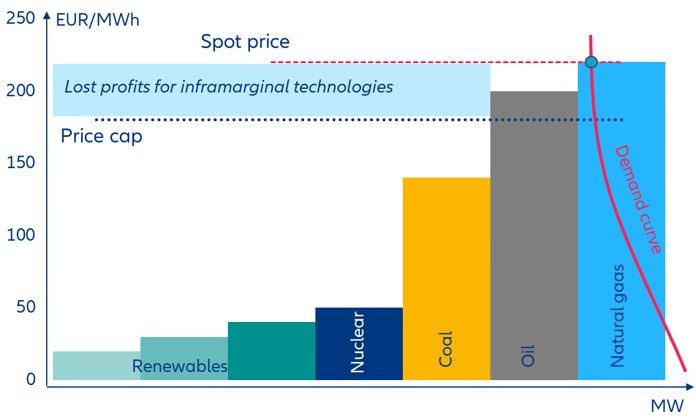

- Revenue cap for inframarginal technologies. A cap of market revenues set at EUR180/MWh for renewables, nuclear and lignite electricity generators. The choice of measures is at the discretion of member states, as well as the decision to set a lower cap for some technologies. The revenues gathered will be redirected towards final customers.

- Solidarity contribution for the fossil fuel sector. A mandatory temporary levy for businesses active in the crude petroleum, natural gas, coal and refinery sectors set at 33% on taxable profits in the 2022 and/or 2023 fiscal year.

- Support measures for small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Member states may temporarily set a price for the supply of electricity to SMEs to alleviate the pressure from the high costs of energy.

As expected, no agreement was found on the issue of a price cap for gas imports, although ministers discussed the matter extensively. While at least 15 member states are in favor of the measure, there are still plenty of technical differences in the proposed approaches. Notably, whether the cap will cover all pipeline gas imports or just those from Russia, and whether a fixed or a flexible cap should be imposed. The main concern is that a price cap could end up in less gas supply for Europe – aggravating the energy crisis.

Figure 1 – Europe: Overview matrix of fiscal measures