EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

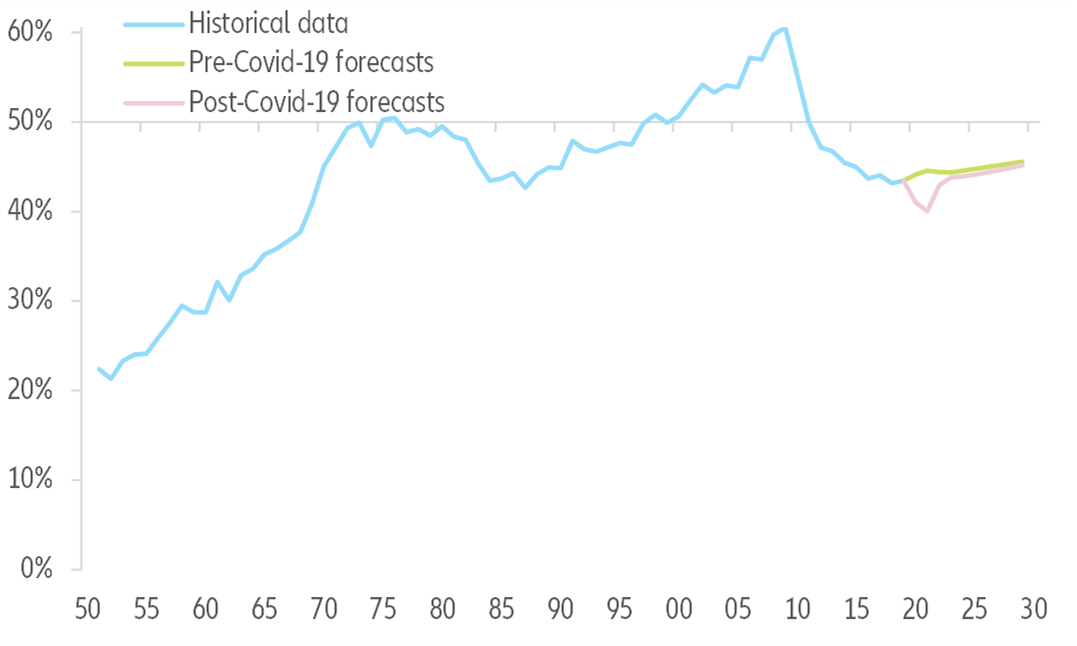

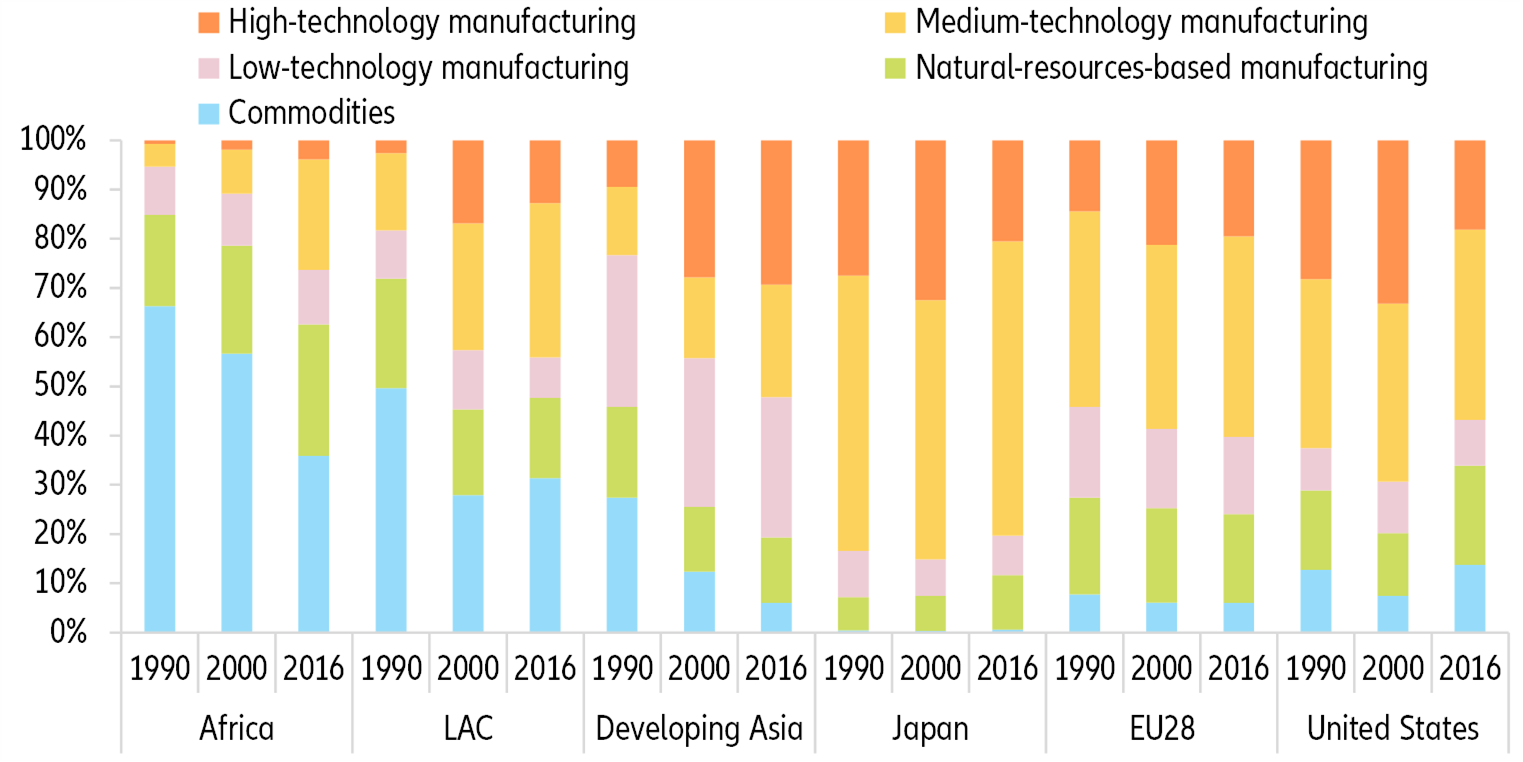

- In 2020, Covid-19 narrowed the prosperity gap between rich and poor countries as the former were at first the most affected. But over the medium and long run, its consequences could hit emerging markets harder. Covid-19 will increase income inequality between richer and poorer countries since the latter have less policy room to mitigate the impact of the crisis and slower access to vaccines. In addition, the crisis may also have accelerated long-term structural trends that will not be favorable to many emerging economies: In the post-Covid-19 world, the comparative advantages of relatively cheap labor – on which the rise of emerging markets and the global middle-class was primarily based – would count for less. In this context, the path to high-income status could become longer and more difficult for these countries.

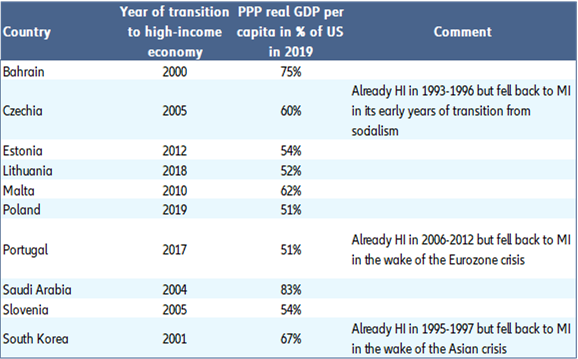

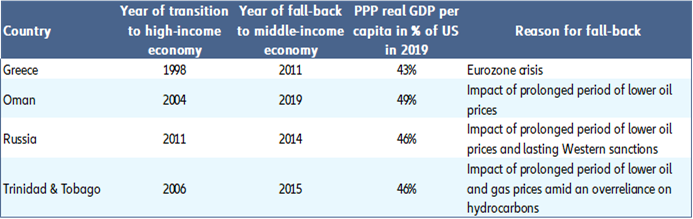

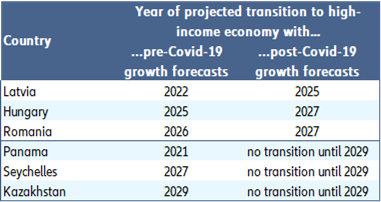

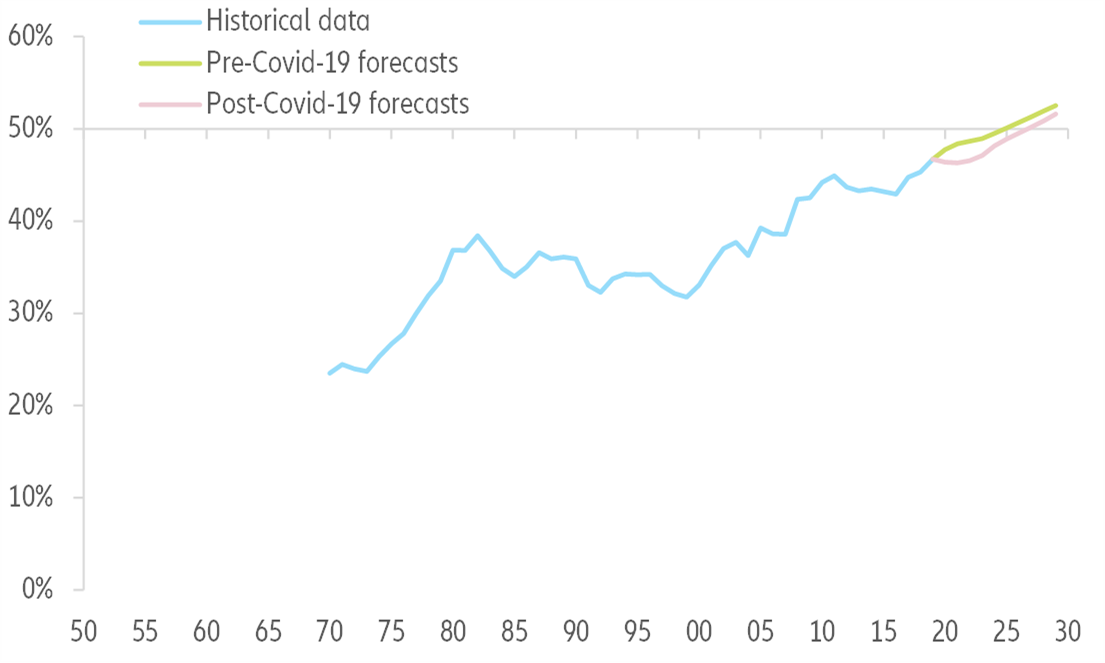

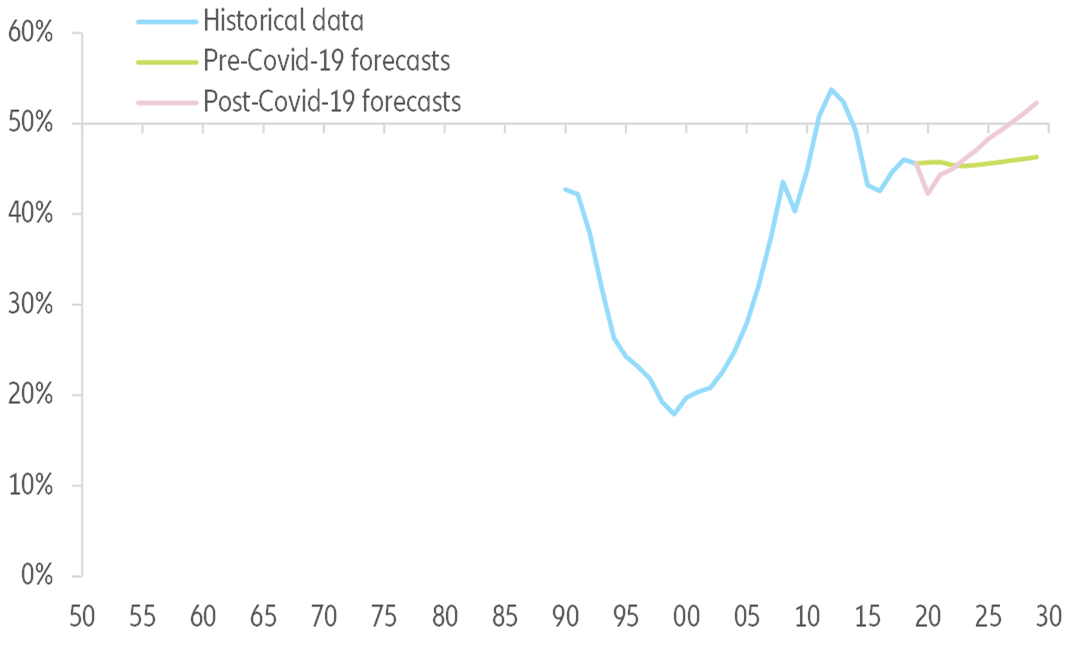

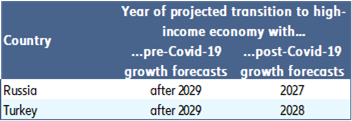

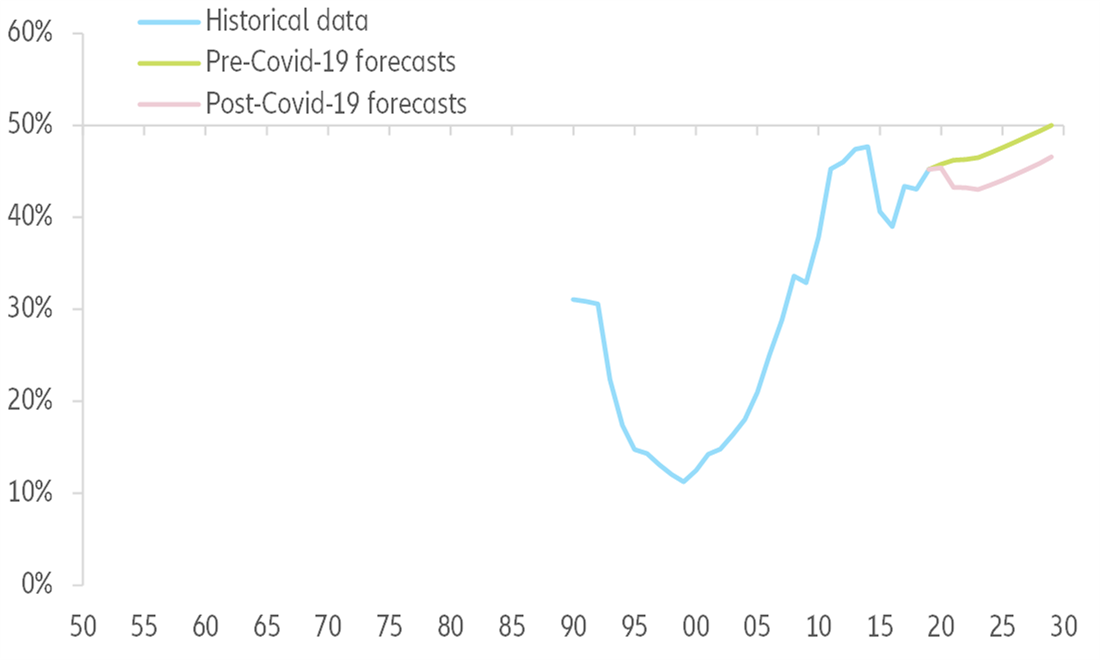

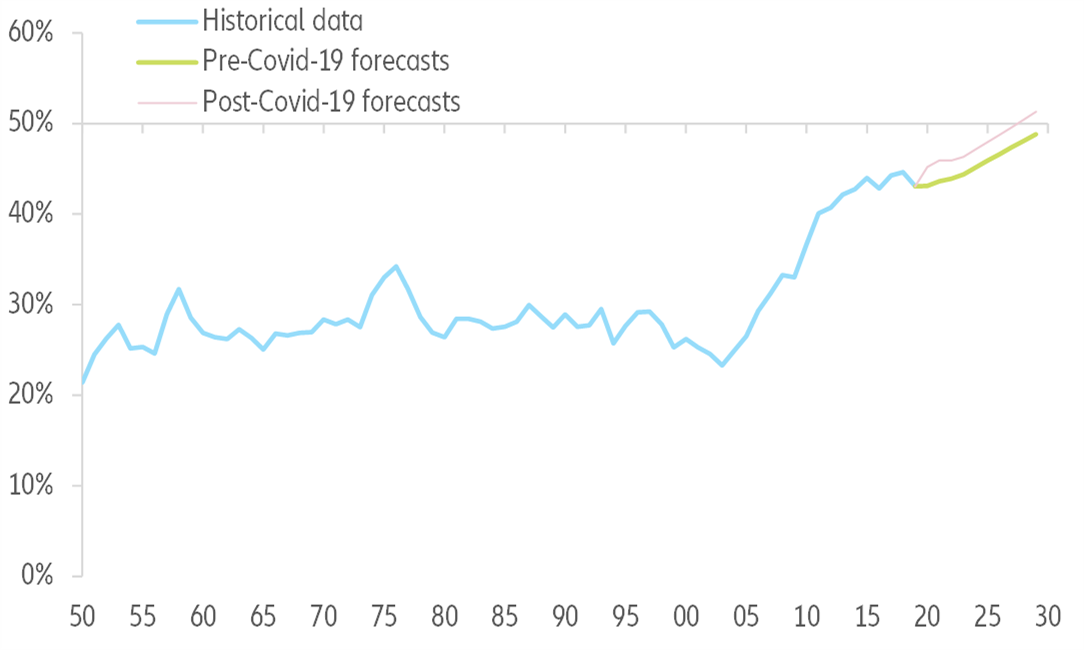

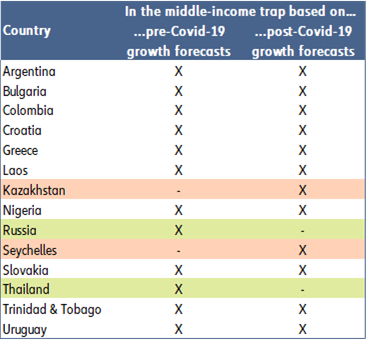

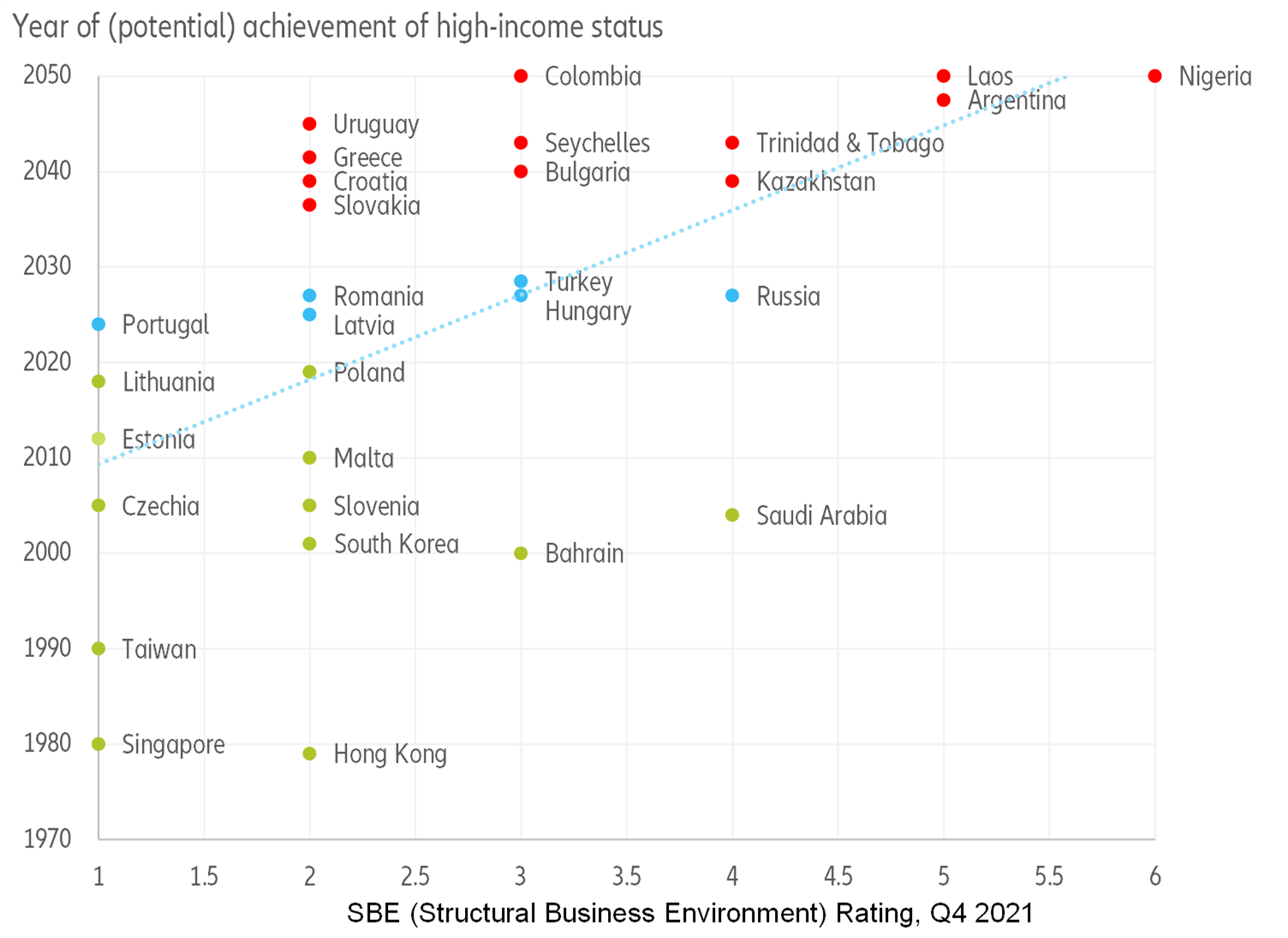

- Which countries are most at risk of facing a middle-income trap? To investigate the potential long-term scarring effects on per capita income, we look at the risk of a "middle-income trap", a situation in which countries that have rapidly transitioned from low-income to middle-income status fail to further catch up to high-income countries. Based on our pre-crisis and post-crisis long-term economic growth forecasts, we find that by 2029, Hungary, Romania and Latvia are likely to see their transition delayed by a few years, though their EU membership will prevent a descent into the middle-income trap. However, Kazakhstan, Panama and Seychelles will not move to high-income status during our forecast horizon. Somewhat surprisingly, Turkey and Russia could achieve high-income status in the medium run sooner than previously expected, likely due to crisis-related fiscal stimuli more than compensating for the initial growth slowdown, thus creating base effects that feed forward, or higher-than-previously-expected oil prices. That said, their long-term outlooks face considerable downside risks, including swings in commodity prices (Russia) and risks to balance of payments, currency and monetary policy (Turkey). Our analysis of long-term catch-up trends further identifies 10 countries (Argentina, Bulgaria, Colombia, Croatia, Greece, Laos, Nigeria, Slovakia, Trinidad & Tobago, Uruguay) that are or will be in the middle-income trap over 1950-2029 – with or without the Covid-19 crisis.

- In this context, the insurance industry has an essential role to play in helping countries overcome the middle-income trap. Many countries that have successfully transitioned to the high-income level have strong insurance markets, and this is no coincidence: Insurance markets contribute significantly to resilience, the crucial ability to cope with crises, thus making it easier for poorer countries to escape the middle-income trap. In this context, the insurance industry must help to close protection gaps by focusing on simpler products, risk prevention and building public-private partnerships – be it for risk protection or infrastructure investments. It’s a fitting task to its corporate purpose.