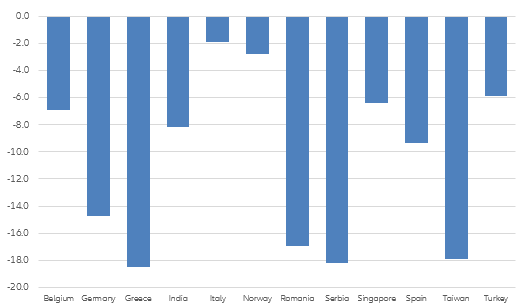

What can be concluded from this study? The grand, uniform narrative of the disappearance of the middle class should be met with suspicion. The data, at least with a view to net financial assets, suggest a more heterogeneous picture. It is noticeable, however, that genuine success stories are rather rare; in most countries, the situation of the middle class has deteriorated, especially with regard to its share of the total wealth pie. Moreover, this share is at a very low level in many countries, and the situation of the middle class appears precarious here. However, similar figures reflect very different realities. Take

Germany (and

Sweden), for example: Here, the low share of the middle class is mainly due to a relatively larger upper class. (Part of it, sociologically speaking, would probably rather count as the upper middle class.) It is therefore worth taking a closer look in any case, and we would caution against jumping to conclusions.

However, despite the generally difficult situation of the middle class, the figures should be encouraging, especially in view of the (few) successes: They show that policymakers certainly have room for maneuver to strengthen the middle of society by, say, sustainable pension systems that allow big chunks of society to participate in capital markets. Distribution issues are not determined by external circumstances – even if the economic conditions of recent years have certainly tended to point in the direction of greater inequality.

A final word about the data itself. In many countries, the data on wealth distribution are still rather unsatisfactory. We therefore make do with population deciles in order to obtain at least an approximate picture of the distribution situation. As usual in purely quantitative studies, we work with threshold values. As a consequence, there may be movements at the edges of the groups, even if the actual wealth situation has only changed by a few hundred euros. Thus, some households are classified in other wealth classes over time, even if the reality of their lives has hardly changed at all. A second weakness of a purely quantitative classification is that it ignores important sociological criteria such as education, occupation and family status, hence our specific definition of the middle class.

What is the future of the middle class after Covid-19? It is still too early to make data-based statements but some trends are already emerging. The direct impact of Covid-19 is more likely to have increased inequality in many countries. Lockdowns and sanitation measures to contain the pandemic have primarily affected jobs with direct social contact, such as those in hospitality and other services. Earnings in these jobs are often below average, while above-average numbers of women and young people work in them. The home office, on the other hand, is primarily a privilege of well-educated and high-earning employees.

This was confirmed in our

Allianz Pulse survey, where 33% of German respondents stated that their economic situation had worsened during the pandemic. However, among 18-24 year-olds, this figure was 43%, while it fell to less than 30% among the over-45s. The differences between men and women were also striking. Among Italian respondents, for example, the ratio of those affected by the pandemic was 41% (women) to 31% (men). There were equally wide divergences among income groups. In France, more than one-third of respondents with low net incomes (below EUR2,000) reported having suffered economically from Covid-19; for higher incomes (between EUR4,000 and 5,000), this proportion dropped to 15%. However, the ratio rose again for top earners (above EUR5,000 net income) as they were likely to include many self-employed individuals who were hit hard. This shows that even the direct effects of Covid-19 are not just black and white.

The picture becomes even more complex when the (very) generous government aid is taken into account. In some cases, this not only stabilized incomes, but also led to overcompensation and thus to rising incomes for those affected, from which poorer sections of the population benefited first and foremost. Initial studies therefore also conclude that income inequality may even have decreased in 2020, at least in the rich countries .

The US distributional financial accounts even suggest that the overall distribution of wealth will not have changed in 2020 either (even if the richest 1% could slightly increase their share of total wealth).

But this state of affairs will be of limited duration. With the expiry of state support, the direct effects of the crisis – the loss of millions of jobs – will once again be felt. Above all, however, another channel of impact is causing concern: Covid-19 led to a significant impairment in education. The consequences – ranging from major gaps in knowledge to dropping out from school – will affect above all the lower educated classes, where there is a lack of education and (financial) resources to compensate for the shortfalls in instruction . Covid-19 is thus likely to further entrench social immobility.

However, there is also an important point that could counteract the further widening of the wealth gap: redistributive policies. Covid-19 was also the hour of fiscal policy, which successfully countered the crisis with billions in support. A return to the status quo ante seems unlikely at present; politicians will want to use their newfound power in the future as well. And in contrast to the financial crisis, when the experience with (extremely) expansive monetary and fiscal policy was still new and the return to stability was high on the agenda, this time the economic policy landscape is fundamentally different. The political shocks of recent years (Trump & Brexit), which have sharpened the sense of the importance of inclusive growth, also contribute to this. So it cannot be ruled out that the structural upheavals looming in the next few years will be politically hemmed in. What this would then mean for long-term growth and prosperity in general is another matter.