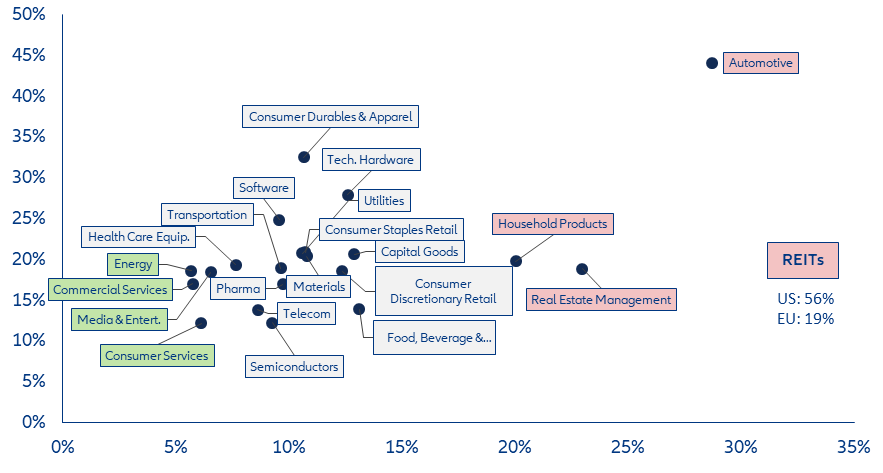

In focus – Sector vulnerability to rising financing costs

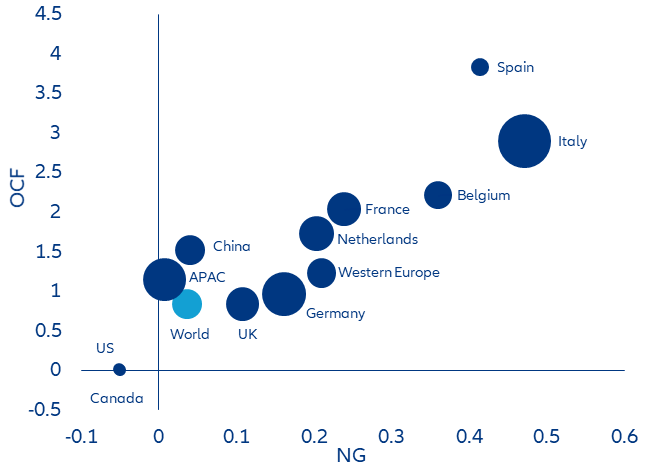

- With a debt/EBITDA ratio of 3.8x on average, US firms are more leveraged than European ones (3.3x). But Europe has a higher proportion of total debt maturing in one year (20% vs 14% for the US). Looking at the operating cash flow coefficient, net gearing and interest coverage, we find that corporates in Italy, Spain, Belgium, France and the Netherlands seem most exposed to a liquidity squeeze.

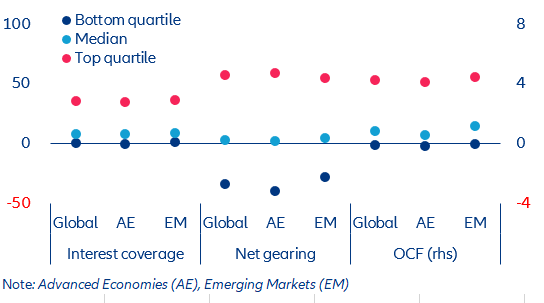

- No rest for the leveraged, notably for those with high debt redemptions in the short run. Companies in advanced economies appear to be safer than those in emerging markets when it comes to their level of indebtedness (net gearing below 2.3% for half of the firms in advanced economies vs 4.9% in emerging markets) and ability to meet financial commitments.

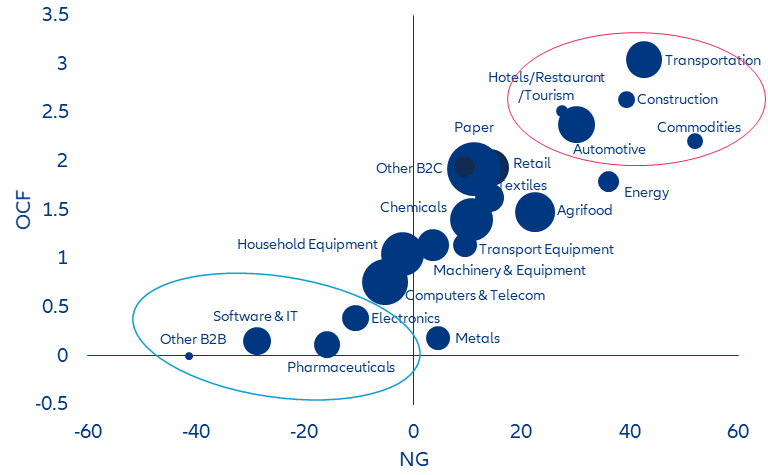

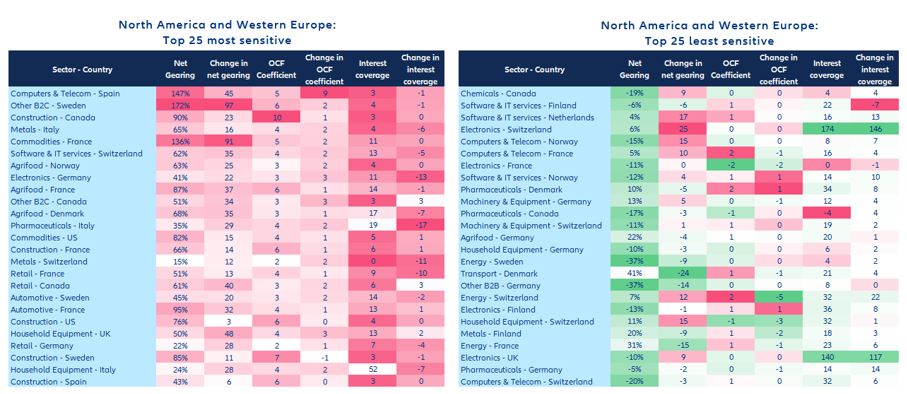

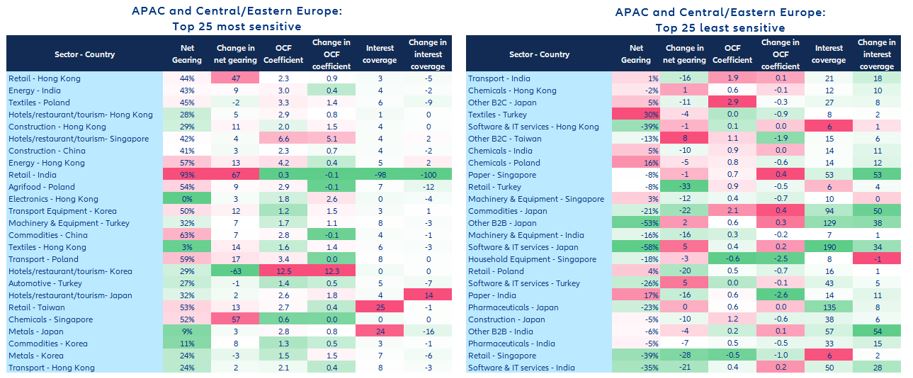

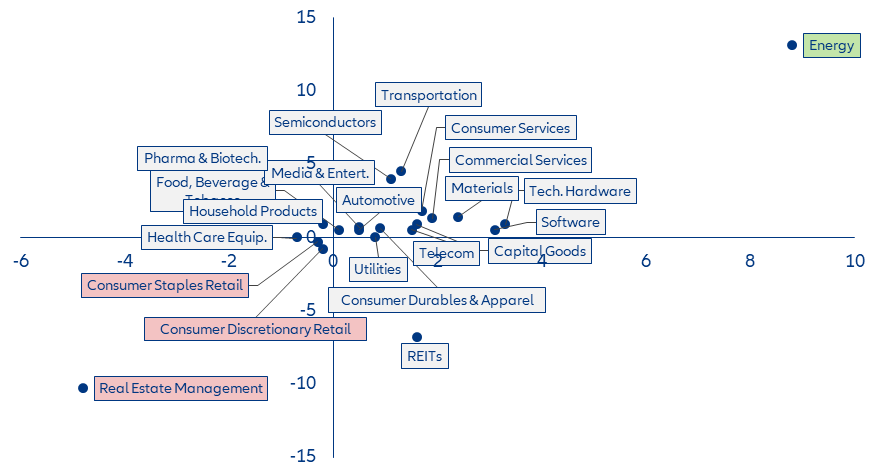

- Five sectors stand out as the most exposed to financing stress: transportation, construction, hospitality, commodities and automotive. Construction and retail top the watch list in both North America and Western Europe. Real estate is the sector most exposed to debt due within one year, followed by automotive, which however has an average current ratio of 1.2x. In Asia-Pacific and Central/Eastern Europe, metals, energy and, to a lesser extent, hospitality and retail are more of a concern.

- Things could get worse as the profit squeeze should become more visible in autumn when we expect the full transmission of interest rates. Overall, we calculate that the equivalent of the full rise in financing costs since 2022 stands above -7pps of the gross value added in Spain, more than -6pps in Italy and France, -4.5pps in Germany and close to -4pps in the US (ceteris paribus). Retail is most affected sector in terms of profitability as it has the lowest operating margins (7.5% for discretionary and 4.2% for staples vs an all-industries average of 15.9%). Stubborn inflation and the intensification of the price war between retailers should exacerbate further the deterioration already observed in 2022.