Executive Summary

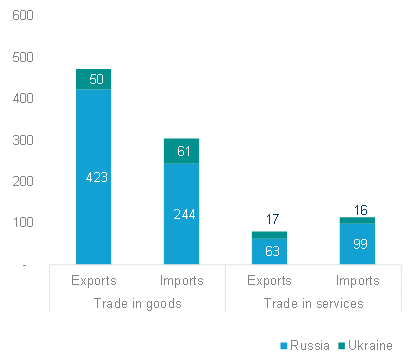

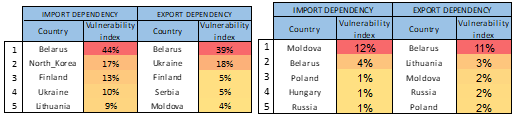

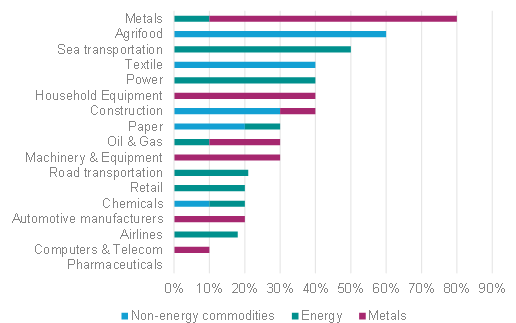

- Global trade exposure to the Russian and Ukrainian economies is limited and has been declining over the past year, which will restrict the direct impact of the war to certain countries (eg. Belarus, Moldova, Poland, Turkey) and sectors (oil & gas, fertilizers, metals, agrifood).

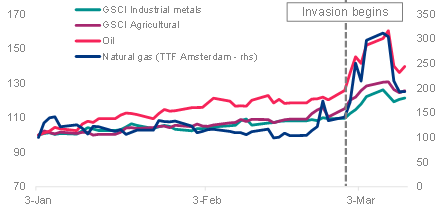

- However, the indirect impact will be global, massive and immediate: The entire global economy will suffer from the current surge in energy and commodity prices, and from additional disruptions in supply chains.

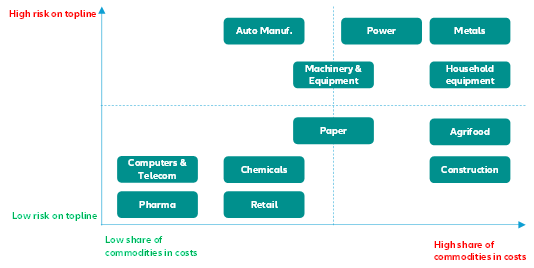

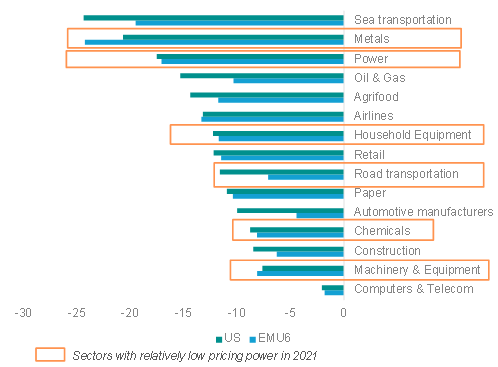

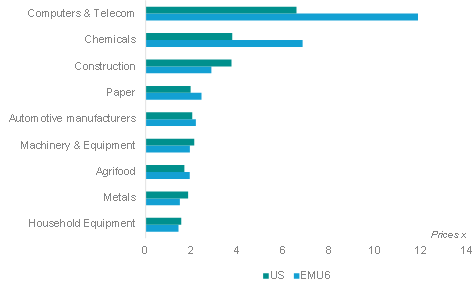

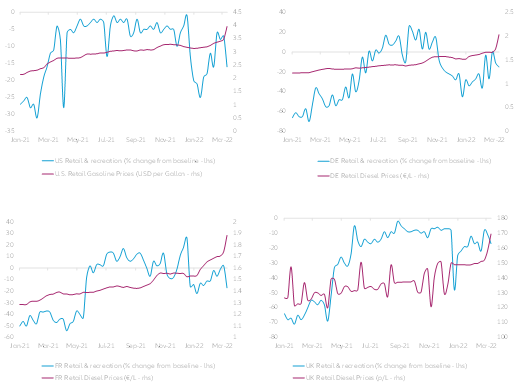

- If oil and energy prices, as well as non-energy commodity prices, remain at current levels, we find that the metals and power sectors are most at risk of a profitability shock and could lose over 20pp of EBITDA margins that were around 30% in 2021.

- A further +50% to 70% rise in non-energy commodity prices could actually wipe out all profits in six out of the nine sectors under analysis. Higher prices could also spark a decline in demand, which would hit the power, metals, household equipment and machinery & equipment sectors the hardest (see Figure 1).

- As governments become increasingly concerned about a prolonged conflict and the increasing negative confidence effects, we expect increased state support measures that could delay a full insolvency normalization in 2022.

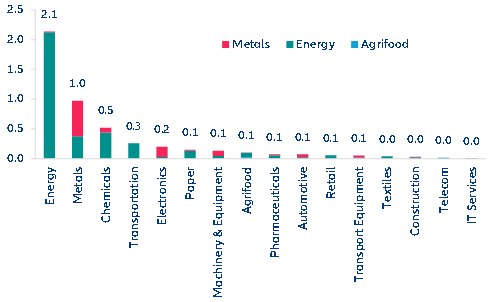

Figure 1 – Revenue vs commodity cost risk mapping